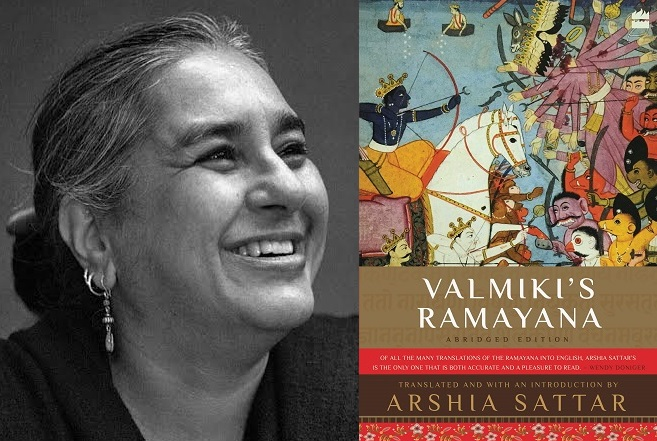

In this conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum, translator, author and director Arshia Sattar talks about her translation of Valmiki’s Ramayana, its genre, Rama’s divinity, the need to retell classics and more.

Indian Cultural Forum (ICF): You mention in the introduction to Valmiki’s Ramayana about the need to retell classics every 20 odd years in order to make them suit a current idiom — accessible and meaningful to contemporary audiences. This is against the notion that “classics” are “museumised” objects that require “special” effort to be accessed. Could you tell us more about this aspect?

Arshia Sattar (AS): The moment a classic becomes “museumised”, it’s not a classic any more. A classic is a story or a text that remains relevant over time and space and across cultures and languages. It continues to engage people with the questions that it asks, if not with the answers that it gives. The Tale of Genji from 11th century Japan remains enchanting even if I read it in 21st century India. Yes, classics require a little more effort to read – they speak differently about things that we consider familiar (such as relationships within a family) or describing a beautiful woman as “gajagamini”, which literally means “one who walks like a female elephant”. They also speak about things that we may never know or experience ourselves, such as a talking monkey or even a king having a hundred thousand slave girls, as Yudhishthira did in the Mahabharata. Classics open us up to different ways of apprehending the world and that could be why we want to “museumise” them. We don’t want to be challenged in our views and our opinions and our ways of being.

ICF: You talk about the “story” as a means to discover the self. This translation shows that even Rama needs to listen to his own story from another in order to remember his divinity. Does this make the act of listening not only for pleasure but also a critical act of redemption that helps in knowing oneself?

AS: All great stories will tell you something about yourself; you just have to willing to receive that perspective. In the Ramayana, this trope (common to many eastern stories) is presented to us in all its narrative glory. For me, one of the most incredible scenes in the Valmiki Ramayana is when the gods return Sita to Rama after she walks into the fire. The gods chide Rama gently for not knowing better, for treating his virtuous wife so cruelly. Such behaviour was not worthy of someone like him, they say. And Rama says, “But who am I? Why am I here? I had always thought that I was Rama, son of Dasharatha . . .” What a human moment! This is a question that all of us have asked ourselves at some point in our lives – “Who am I and why am I here?”

The act of listening to one’s own story is not an act of redemption, it’s an act of recognition. The two are not always the same thing. Rama hears the story of his life from his own sons, whom he does not recognise because they were born away from him and lived away from him. But when he hears his story, he becomes aware of how unfairly he has treated Sita and asks for her to be brought to his great sacrifice. Rama is able to see what he has done from the objective distance that the story has just given him.

For people like you and me, far more mundane than Rama, hearing about yourself from someone else tells you how other people see you. Surely that’s a good thing. You can feel confident in all that people appreciate about you and think about addressing the less pleasant parts of yourself, parts that perhaps you had never been aware of. My mother was recently telling someone about a certain part of my life and I was astounded at all that I had forgotten about that time. I might have subconsciously erased some of what she was talking about. It was a real revelation. And it was a very useful one. Things that happen in the epics, or in classical stories, can also happen to us. It’s just the scale that will be different.

ICF: When one argues that the retelling of a story is significant because it keeps the text dynamic, it naturally also means that there is virtue in considering our literary treasures “works in progress” as opposed to the idea that these are texts with rigid, fixed narratives.

AS: All our great traditions and our most profound thinkers, ancient and modern, have held firmly to the idea that our texts, literary and sacred (apart from the Veda) are dynamic and responsive to their times. Let’s not forget that our texts were created and nourished in an oral tradition, where tellers had the right to tell a story the way they wanted. That continues vigorously even today with kathakars, who tell the Manas and the Bhagavata, for example, each in their own inimitable style year after year. We also see this in the performances of folk theatre, be it Ramlila or Yakshagana — the actors and storytellers respond to the audience, to the historical moment, to a local event.

It’s only recently that we’ve had people obsessing over the idea of a single narrative, the idea that there can only be one “legitimate” version of Rama’s story. That, too, is a response to a political exigency, to an ugly impulse towards social and religious divisiveness and exclusion. I think it’s wonderful that so many of us talk to the Ramayana, we all want to own it, to tell it in ways that it reflects ourselves and our realities. And the Ramayana is a generous enough text to respond to us all – whether we’re brahmin or muslim or dalit or women or people of indigenous communities.

ICF: It’s difficult to frame Ramayana within a particular genre — is it an “epic” in the Western sense, is it “kavya”, or “nataka”? How do you identify Ramayana in terms of its genre while also addressing the religious significance of the text? If we’re calling it a “kavya” that is sacred, can we say that it is sacred in terms of its literary value and capacity for reinterpretation?

AS: It’s certainly an epic in terms of western literary genres, sharing structures, a milieu, character types, episodes and concerns with other great stories like the Odyssey and Nibelungenlied. Acknowledging this doesn’t diminish the Ramayana in any way, rather, it expands and enhances it to live and breathe in a larger and more universal literary landscape. Of course, the fact that our hero is god and that he acts within a framework of karma and dharma make this a deeply Hindu text.

The Ramayana speaks of itself as kavya and so that’s a nomenclature that we need to take seriously. This probably refers to the ornate language of the Sanskrit text, studded with similes and metaphors. This nomenclture also distinguishes it from the Mahabharata, whose language is very different and which calls itself “itihasa”, a word that has come to mean history in many modern Indian languages. Kavya, thus, refers to the language and not necessarily the content of the Ramayana.

I don’t think Valmiki’s Ramayana is a nataka in form or in content, though of course, there are natakas that are based on it. Some, like the so-called Hanuman Nataka is “lost” and others, such as Bhavabhuti’s Uttararamacharita, are exemplars of their genre.

As far as I know, kavya is an essentially secular literary genre. The Ramayana becomes a sacred text because it purports to be about how god acts in the world, its literary value is something else all together and is there for anyone to see. This is true of Ramayanas in other Indian languages as well. They often stand as the most beautiful literary works in those languages — this is certainly true of Kamban’s Tamil Iramavataram and Tulsi’s Ramcharitmanas.

ICF: In Valmiki’s Ramayana you talk of Dasaratha’s idea of Ayodhya, which is described as “righteous” and “disciplined”, with the caste order in place. How does one retell the “ideal” — the “ideal king” for instance — when it overturns our contemporary notions of equality and utopia?

AS: I’m a translator, it’s my job to present the text as it is. If the Valmiki text describes the prosperity and stability of Ayodhya as being predicated on a firm and unshakeable caste order, it would be highly problematic if I were to bring that to readers in any other way. People like Ashok Banker and Amish retell the Ramayana story, as do C Rajagopalachari and RK Narayan, in an earlier period. My impression is that they either gloss over this difficulty or they parse caste order as being horizontal rather than vertical.