Tawaifs have played a crucial role in the social and cultural life of northern India. They were skilled singers and dancers, and also companions and lovers to men from the local elite. It is from the art practice of tawaifs that kathak evolved and the purab ang thumri singing of Banaras was born. At a time when women were denied access to the letters, tawaifs had a grounding in literature and politics, and their kothas were centres of cultural refinement. Yet, as affluent and powerful as they were, tawaifs were marked by the stigma of being women in the public gaze, accessible to all.

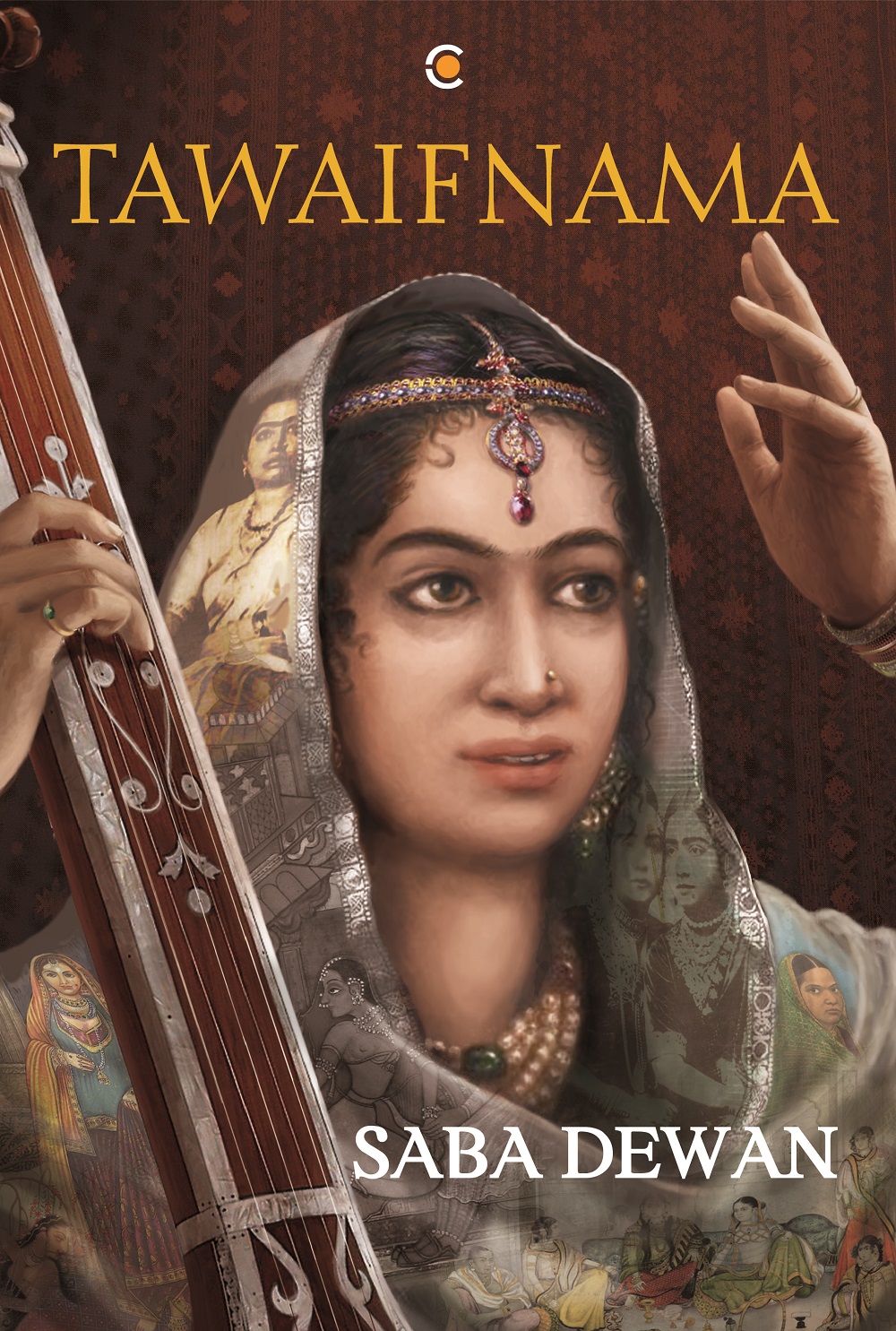

In Tawaifnama, through the stories and self-histories of a family of well-known tawaifs with roots in Banaras and Bhabua, Saba Dewan explores the nuances that conventional narratives have erased, papered over or wilfully rewritten.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Sadabahar, the Tawaif” of the book.

‘Sadabahar’s life as a popular tawaif in Shahabad shimmered with the light and colour of mehfils No musical gathering, including those organised by the biggest Rajput zamindars and rajas of the region, was deemed a success unless Sadabahar had performed in it. Her earnings were considerable, making her family the best-off among tawaifs in Chainpur. Bit by bit, Bullan and Kallan were able to free the house and agricultural lands that they had mortgaged to take care of Sadabahar and Gulshan.’

Sadabahar was the only tawaif in Chainpur, you say with obvious pride, who had her own horse-drawn carriage. She loved going out on rides with its hood drawn back, revelling in the looks of admiration and envy that came her way.

I am reminded of a similar anecdote about the acclaimed tawaif-diva Gauhar Jan of Calcutta in the late nineteenth–early twentieth century, who enjoyed taking evening rides through the city in her carriage drawn by four white horses. A particularly favoured route, it seems, went through the white quarters of Calcutta, in flagrant violation of the law that denied access to Indians. Gauhar is supposed to have thought nothing of paying a hefty fine whenever the desire to ride through the white area overtook her.

The tawaif here is a figure charged with sexuality, and proclaiming with flamboyant confidence not only pride in her identity as a public woman but also her power to access and use at will the public space, a privilege reserved for men from the feudal aristocracy and Europeans. This reversal of socially sanctioned gender rules is reflected in your telling of Sadabahar’s story as well.

At her home in Chainpur, Sadabahar was looked after much like senior earning male members are in patriarchal households. A mini-army of relatives and retainers lived in Bullan and Kallan’s house, dependent entirely upon her generosity for their survival. In return, they were obliged to make themselves useful. If Sadabahar wanted a hot meal on her return home after a late-night performance, then someone would be woken up to cook whatever she desired. If she complained of aching limbs, someone would give her a massage, all night long if necessary.

Yet Sadabahar did not allow the luxurious living, or the heady exhilaration of having lovelorn admirers, expensive gifts and lavish praise, diminish her commitment to music. In all seasons, every day, mid- morning, her old ustad Bhure Khan would troop in for lessons as he had always done. Until, one day, he did not come.

It was such an unusual occurrence that a worried Sadabahar sent someone to his house to enquire about his well-being. One of those merciless fevers that regularly swept through Shahabad district had taken a grip of her old teacher. Worse, there was no one to look after him. Over the decades, his family tree had branched off in different directions, and the men and their immediate families had migrated to various zamindaris in search of patronage as musicians. Bhure Khan Sahib, his old body feeble with high fever, lay alone, surrounded by flies and the spectre of imminent death.

As soon as she heard this, Sadabahar set off to bring her ustad to her own home. Here, she tended to him like a daughter. The best hakim in the entire district was summoned to take charge of his medical needs. Heedless of her own sleep or hunger, Sadabahar sat by Bhure Khan Sahib’s side constantly, mopping his brow, feeding him and cleaning without hesitation his soiled clothes and bedsheets.

One morning, the ustad seemed to be feeling much better. Some colour had returned to his lips and his eyes too shone again. Motioning to Sadabahar, he asked in a surprisingly strong voice, ‘How long has it been since you last did riyaz?’ Her eyes welling up, Sadabahar said nothing. ‘This just won’t do, girl!’ her teacher exclaimed crossly. ‘Go and get your tanpura and settle down to some singing.’ Sadabahar said a silent prayer to Allah for sending her teacher back to her. She ran and brought her beautifully carved tanpura into his room and, settling down on the floor, began strumming it gently.

On his instructions that morning, she sang Babul mora naihar chhuto hi jaye; Father, my maternal home slips away. Said to have been written by the last nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, when he was exiled by the British from Lucknow to faraway Calcutta, the thumri set to raga Bhairavi was very different from the fast-tempo, bol-baant style of

bandish thumris that were generally the staple of Sadabahar’s repertoire. Slower in tempo and deeply reflective in tone, the song had reached Bhure Khan Sahib fairly recently through a relative based in Banaras. Profoundly impressed, he had been teaching it to Sadabahar just before he took ill.

At one level, the cry of a young bride forced to leave the sanctuary of familiar faces after marriage, at another, the thumri is also a song of the exile from a beloved homeland. At a third level, it is a meditation on death: of the journey made by the soul away from mortal life. Her eyes shut, Sadabahar sang with passion and precision, bringing out the multiple meanings embedded in the deceptively simple lines of the song. Char kahar mili doliya utthaye, apno begana chhuto jaye; Four bearers together carry my palanquin, Loved ones and those estranged, both slip away.

This would be her finest performance ever. There was silence in the room when Sadabahar concluded the thumri. She opened her eyes to find herself alone. In the course of her song, her teacher had taken his leave from the mortal world.

Sadabahar had loved her old teacher, mentor and guide like a father. He, in turn, generously shared with her his greatest treasure: music that could neither be bought nor stolen. She knew that this was a debt she could not hope to repay; the best she could do was to fulfil her duties and obligations as a disciple, a shagirda. There is a saying amongst the Dharis that a tawaif is the best son a sarangiya, sarangi player, can hope for in his old age. Sadabahar was proof of its truth. Just as she had looked after her teacher when he was alive, she left nothing wanting in his funeral and after-rites.