A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court has unanimously held that the possession of the most-contested piece of land in Indian political history—the 2.77 acres where the Babri masjid once stood—should in fact be exclusively given to the Hindu claimants. At the same time, the court invoked its special power to do “complete justice” under Article 142 to recompense the damage caused by the “egregiously illegal” installation of idol in 1949 and the masjid’s demolition in 1992. Hence, it ordered the government to allot an alternate plot of 5 acres to the Sunni Waqf Board at a “prominent place” in Ayodhya for the construction of a mosque.

A few words have become an indispensable part of the vocabulary describing this judgment. Politicians and legal commentators alike are calling it a “win-win situation”, BJP spokesperson Nalin Kohli calls it an “inclusive judgment”, whereas PM Modi calls it “a golden chapter in the history of the Indian judiciary”. On the other hand, even as the judicial outcome has come to represent a vindication of the ideological Hindutva, many have stated that the majoritarian context and atmosphere has cast its shadow on the court’s narrow and technical reasoning to hold that on the balance of probabilities, Hindu parties have a better claim to adverse possession of the site.

Be that as it may, across the board there seems to be a concealed satisfaction, as if by upholding the claims of the Hindu majority, the court has averted a crisis. However, the finer aspects of the rule of law seem to have been compromised or diluted in order to satiate the faith and belief of a community.

Rule of law requires that people be governed in a manner that is equal, just, and non-arbitrary. The court, citing SR Bommai v UOI, repeatedly emphasises that secularism and fraternity is a basic feature of the Constitution (see paragraphs 82 and 83 of the judgment). It then strongly affirms the constitutional value and significance of the Places of Worship Act, 1991, while strongly affirming the principle of non-retrogression of colonial-era disputes.

The court, emphasising the legislative intent behind the act, states, “The law is hence a legislative instrument designed to protect the secular features of the Indian polity, which is one of the basic features of the Constitution. Non-retrogression is a foundational feature of the fundamental constitutional principles of which secularism is a core component. The Places of Worship Act is thus a legislative intervention which preserves non-retrogression as an essential feature of our secular values.”

Hence the court raises this statute to the pedestal of a constitutional statute whose importance has been highlighted by various secular and progressive activists in the last few days, considering the likelihood of similar communal disputes being raised in other places of worship in Mathura and Varanasi. This is an important signal from the court and any derogation from the judicious application of the act would certainly be violative of the court’s reasoning.

The court remarks that “title cannot be established on the basis of faith and belief above” (para 788). And yet, the court proceeds to say, “Once the witnesses have deposed to the basis of the belief and there is nothing to doubt its genuineness, it is not open to the court to question the basis of the belief”; “whether a belief is justified lies beyond ken of judicial inquiry” (para 555). Professor of law, Faizan Mustafa, notes, “The court while pronouncing the judgment did try its best to strike a balance between law and faith. But clearly faith has the last laugh here.”

While it is undisputed that a significant section of the Hindu population believes Ayodhya to be the birthplace of the Hindu god, Rama, it is unclear whether such belief can be grounds for legal adjudication in what is essentially a title dispute. Furthermore, such deference to religious beliefs also stands in opposition to the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Sabarimala case, wherein the court explicitly favoured constitutional morality over any personal/religious beliefs. “In the public law conversations between religion and morality, it is the overarching sense of constitutional morality which has to prevail” (para 189, Indian Young Lawyers Association vs. State of Kerala).

It remains to be seen what the Ayodhya ruling’s jurisprudence bears for the review petition in the Sabarimala case, in which an order is expected next week.

Another instance of the court deferring in favour of the belief of Hindu devotees is where it disregards the long-standing bifurcation of the disputed site between an inner and outer courtyard. “Despite the setting up of the grill-brick wall in 1857, the Hindus never accepted the division of the inner and the outer courtyard. For the Hindus, the entire complex as a whole was of religious significance. A demarcation by the British for the purposes of maintaining law and order did not obliterate their belief in the relevance of the “garbhagrih” being the birth-place of Lord Rama.” (para 773).

The court uses this logic to treat the entire disputed land as one unified territory—which it then proceeds to grant to the Hindu claimants. Again, this is a problematic deference to the belief of one community in disregard of the factual matrix (wherein Hindu devotees had initially only staked claims to the Ram chabutra, located in the outer courtyard). The suit that mahant Raghubar Das had filed on January 19, 1885, sought permission to build a temple on the chabutra. The district judge, dated March 26, 1886, ruled: “This chabutra is said to indicate the birthplace of Ramchander.”

Nevertheless, it is important to not lose sight of a greater crisis that has been averted in Indian jurisprudence. In a context where large scale mass-mobilisation for temple construction was threatened and it was declared that a Ram temple was an issue of faith and the Supreme Court must not delay its adjudication, the court has successfully engendered unanimous support for legal process.

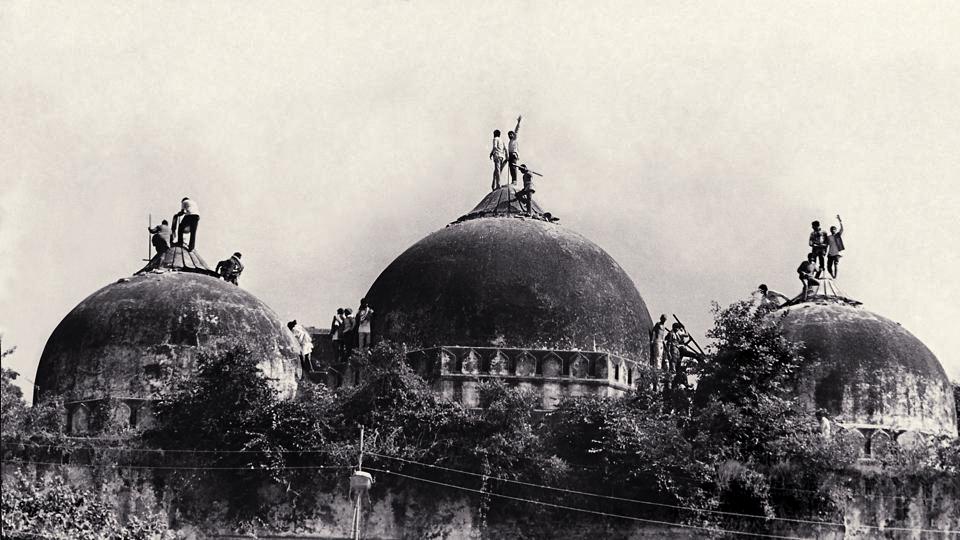

The court takes due notice of the unruly demolition of the Babri masjid too. “The damage to the mosque in 1934, its desecration in 1949 leading to the ouster of the Muslims and the eventual destruction on 6 December 1992 constituted a serious violation of the rule of law.” (para 788, clause XVIII). And yet, the court refrains from restitution by restoring the mosque to the Muslim community. The judgment seeks to establish a precedent wherein minorities are simply compensated for violations of rule of law, as opposed to reverting to their original positions with due respect for their rights and dignity. It is also worrisome because the same perpetrators continue to enjoy to impunity and gave self-congratulatory statements on the verdict.

AG Noorani’s critique of the Allahabad High Court’s judgement is equally applicable to that of the Supreme Court: “The Allahabad High Court had, in effect, sanctified the criminal conversion of the historic Babri masjid, built in 1528, into a Hindu temple in 1949.”

The political ramifications of this judgment will not be immediately discernible. Long ago, in 2001, the historian Mukul Kesavan had written in his book, Secular Common Sense, that the construction of the Ram temple “where the Sangh Parivar wants it built won’t lead to apocalypse. The world will look the same the morning after, but the common sense of the Republic will have shifted. It will begin to seem reasonable to us and our children that those counted in the majority have a right to have their sensibilities respected, to have their beliefs deferred to by others. Invisibly, we shall have become some other country.”

Of course, the Supreme Court has averted an immediate crisis. There has been no outbreak of violence, nor reports of bloodshed in the aftermath of the verdict. Perhaps, the greater crisis that the court has involuntarily invited is that of minorities losing their faith in the judiciary. Today, the legislature and executive are turning brazenly majoritarian while vulnerable minorities have nowhere to go than repose their faith in the judiciary. One can only hope it lives up to that faith.