Rarely has a day passed, over the last one week, without the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh announcing a measure to ensure that the Supreme Court’s verdict in the Babri masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi case, also known as the Ayodhya title dispute, does not plunge the country into a communal mayhem.

The RSS has cancelled all its programmes requiring a gathering, instructed its pracharaks, or full-time workers, to stay put in their areas, and cautioned its supporters to refrain from posting provocative statements on social media or engage in triumphalism in case the Supreme Court verdict favours building a Ram temple in Ayodhya.

These measures are indeed welcome.

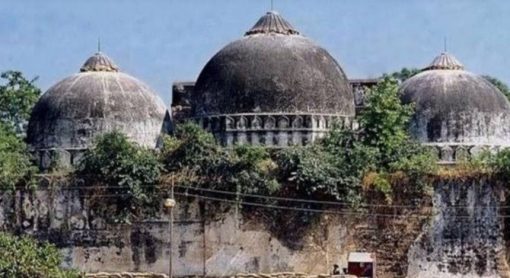

Yet the RSS’ display of sagacity has come three decades too late. During this period, its movement to build the Ram temple in Ayodhya gradually widened the chasm between Hindus and Muslims until it seemed almost unbridgeable with the demolition of the Babri masjid on 6 December 1992. The RSS’ demand had been to build a temple at the Babri masjid site, which it claimed was where Lord Ram was born.

On 6 December, Sangh leaders, including those from the Bharatiya Janata Party, watched as kar sevaks, or religious volunteers, who were estimated to be well over a lakh, fell upon the mosque to reduce it to rubble. These Hindutva stalwarts later claimed that the mosque was destroyed because of the spontaneous outburst of kar sevaks, who were neither amenable to persuasion nor control.

For those born in, say, 1992, the Sangh’s precautionary measures today would seem a case of the organisation realising the risk inherent in collecting a large crowd at places deemed communally sensitive, on occasions likely to provide the spark to light a communal fire. It will have the millennials applaud the RSS for taking measures to obviate the outbreak of rioting.

But what the millennials will not know is that the entire Indian political class, between 1989 and 1992, considered the peak of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement, would regularly beseech the Sangh Parivar to desist from behaving irresponsibly. For instance, not to gather kar sevaks in Ayodhya every few months to pressure the Centre to hand over the Babri Masjid site to them. Or try, instead, the alternative route of negotiations and work out a compromise, or wait for the judicial verdict on the Ayodhya title dispute.

But the RSS claimed the Ayodhya issue was outside the judiciary’s purview. The Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP national executive, on 11 June 1989, adopted a resolution in Palampur which said, “The BJP holds that the nature of this [Ayodhya] controversy is such that it just cannot be sorted out by a court of law.”

This line was reiterated by BJP leader AB Vajpayee, who later became the prime minister. In a letter to Communist Party of India leader Hiren Mukerjee, Vajpayee wrote in 1989, “…In such sensitive matters such as this dispute, which has touched the sentiments (and that too religious) of a large section of the people, the court decision will be extremely difficult to implement.”

These quotes from the past might surprise millennials, who cannot be faulted for interpreting the RSS’s precautionary measures as a sign of its willingness to accept the Supreme Court’s verdict. After all, the RSS said last week that “everyone should accept” the Supreme Court verdict with an “open mind.”

The millennials need to think again.

In November 2017, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat had said, “The Ram temple will be built at the Ramjanmabhoomi and nothing else will be constructed on the land.” Bhagwat’s comment had come just a week before the Supreme Court was to begin hearing the Ayodhya title dispute, on 5 December, which was subsequently posted for another date.

The RSS chief’s remark prompted Justice A M Ahmadi, the 26th Chief Justice of India, to tell this writer, “I would say, Bhagwat’s statement is a form of influencing the outcome of the hearing on the Ayodhya matter… Some may view Bhagwat’s remark on Ayodhya as putting pressure on the bench which is to hear the matter.”

Bhagwat’s Vijayadashami speech of 2018 could also be construed as another attempt to influence the judiciary. He said, “The place of Janmabhoomi is yet to be allocated for the construction of the temple although all kinds of evidence have affirmed that there was a temple at that place.” Earlier this year, Bhagwat, once again, insisted that only a temple will be constructed in Ayodhya. His position contradicts the Centre’s undertaking to the Supreme Court, recorded in the Ismail Faruqui case, that both a temple and a mosque would be built in Ayodhya.

It is hard to tell whether Justice S A Bobde, who is due to become the next Chief Justice of India later this month, had Bhagwat in mind when he said, “Some have great freedom of speech. There has never been an era where freedom of speech has had such width for some people.”

Yet, quite ironically, after repeatedly using the “width” of his freedom speech to insist that only the Ram temple could be built in Ayodhya, Bhagwat’s organisation wants citizens to accept the Supreme Court’s judgement with an “open mind.”

Perhaps this contradiction arises from the Sangh’s conviction that the arguments of the Hindu side in the Ayodhya title dispute will persuade the Supreme Court to assign the Babri masjid site for building the Ram temple.

Perhaps its confidence stems from the legal history of the Babri masjid, which was converted from a mosque to a temple over 125 years, between 1885 and 2010, largely through judicial verdicts, as this story based on AG Noorani’s The Babri Masjid Question: 1558 and 2003; Volume I and II brings out.

Or perhaps the Sangh does not want communal tension to occur now, as the BJP is in power at the Centre and in Uttar Pradesh. Such an eventuality will be yet another testimony against the Modi government already in the dock globally for its treatment of religious minorities, best exemplified by more than two months of lock-down in Kashmir.

This was evident from an Indian Express quoting a source who attended a meeting presided over by RSS joint general secretary Dattatreya Hosabale. The source quoted Hosabale saying, “Whether the judgement is in our favour or not, we should accept it and then decide on the next strategy. But if there is disturbance in the society after judgement, it will go against us and our governments in the state and the Centre.”

But what the millennials will not know is that the RSS was shockingly irresponsible between 1989 and 1992. It cared little about pushing the country into the communal chasm, presumably because, as Hosabale’s remarks of last week suggest, the BJP was not in power and could, therefore, blame others for the violence.

A grisly picture of the violence during that period is portrayed by Violette Graff and Juliette Galonnier in Hindu-Muslim Communal Riots in India II (1986-2011), a section in the Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, which the Paris Institute of Political Studies, popularly known as Sciences Po, maintains.

They link the Sangh’s 1989 shilanyas programme, which involved towns and villages sending consecrated bricks to Ayodhya for building the Ram temple, to the riots in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, and Bhagalpur, Bihar. In Bhagalpur, 396 people died in the violence, but it is likely, Graff and Galonnier say, that more than a thousand lost their lives.

On 25 September 1990, BJP leader L K Advani undertook a rath yatra, styled as a pilgrim’s journey from Somnath to Ayodhya, which left behind a bloody trail. Sixty-six people died in Karnataka and 50 in Jaipur, Rajasthan. In Bijnor district, Uttar Pradesh, 48 people died, although Graff and Galonnier say that unofficial sources put the death toll at 200.

In Hyderabad, Telangana, 134 people died, but the actual count could have been anywhere between 200 and 300. In Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, the official death toll was put at 75, but the People’s Union for Civil Liberties claimed that over 150 people were killed. I have not listed places where the violence claimed 30 or fewer lives.

After the Babri Masjid was demolished, Surat was caught in a cycle of violence. Graff and Galonnier write, “These riots claimed 180-190 lives, according to media reports. But from other sources, even a figure of 200 dead would be an underestimation.”

Mumbai reported 210 deaths and other parts of Maharashtra another 57. “The actual death toll, however, probably amounted to more than 400,” the authors write. A second round of rioting followed, in January 1993, in Mumbai, claiming another 557 lives, or so official figures say. This was followed, in March, by retaliatory serial bomb blasts in the city, killing 257 people. Once again, I have left out cities where the magnitude of violence was nowhere compared to Surat and Mumbai.

The millennials will also perhaps not know about the criminal case pending against BJP leaders, including Advani, who were accused of hatching a conspiracy to demolish the Babri masjid. This case is still at the trial stage, even though the Supreme Court is all set, within days, to decide whether the Babri Masjid site belongs to Hindus and Muslims.

The implication of this ironical situation was vividly brought out by Justice MS Liberhan, whose commission of inquiry concluded that the Babri masjid demolition was “meticulously planned.” A few days before the Supreme Court was to begin hearing the Ayodhya title suit from 5 December 2017, Justice Liberhan said, “If it is decided that it [Babri masjid] is Waqf property, then one side is established as guilty of demolition. And if the Hindu sides get it, then the act of demolition becomes seen as ‘justified’ – to reclaim own property.”

The RSS’ reasonableness today is in sharp contrast to its past conduct, even though it is still welcomed. This change serves an instrumental purpose other than evading the charge of stoking communal conflicts: Discredit the narrative in which the RSS symbolised the darkness at noon.