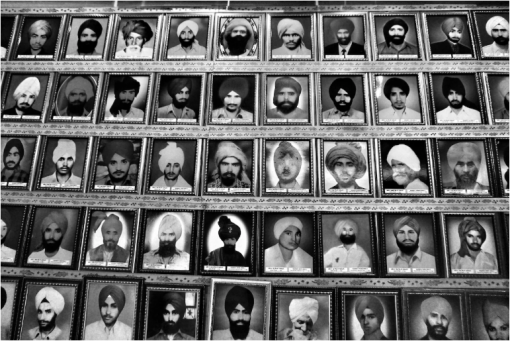

Ever since the 1984 anti-Sikh riots claimed at least 2,700 lives in Delhi and another 3,500 across the country, its victims have been told to “forget” their suffering and focus on the future. For a moment, put yourself in the shoes of these victims and survivors. Some independent estimates say more than 17,000 were killed by violent mobs in the aftermath of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination by her bodyguards.

Recall the gory events as they unfolded 35 years ago to try and understand the inhuman circumstances the Sikh families were plunged into during those blood-soaked days. Empathy with survivors and family members of those who were killed can lead to only one inescapable conclusion: it is impossible to “forget” such events. Can forgetting even be a path to reconciliation?

For those who bore the brunt of the violence, there is no possibility of reconciliation without justice. That is why it is imperative to empathise with and comprehend the pain and agony of the victims. That is the only way to comprehend the the importance of justice.

Let me walk you through some of the unknown and often ignored stories of the victims, who clamour and crave for closure in the form of justice. Travel their painstaking journey in their voices on the 35th anniversary of the violence:

Shamni Kour lost her husband, son and eleven immediate family members in the riots. Here is what she went through: “I remember hearing news of violent clashes around my place, but I was not worried about my family’s safety because we did not kill Indira. In some time, I realized my mistake. Even the police did not protect us. Rather, they were equally complicit in what turned out to be a massacre.”

She clearly recounts her son and husband being beaten to death by goons wielding sticks. She left her home with a little money and gold. Later, all of her belongings were robbed and the perpetrators tore her clothes.

Shamni continues, “We spent three nights in the Chilla Gaon [in Delhi] to stay away from what was unfolding outside. It has been 35 years with no justice whatsoever. We feel helpless. The mob killed our men and women were raped. Our people were burnt and houses looted. However, the custodians of our protection did not care.”

To Shamni, the events of those days “felt like the Partition, when nobody cared for the common people. Are we not Indian citizens? We have faced atrocities at the hands of our people.”

Till date, Shamni feels stuck in 1984. She is looking for some help from the government, but to no avail.

“Every day, the riot plays itself back before our eyes as if it had happened yesterday.”

Nirmal Kaur’s parents hurriedly tossed her and her siblings into their neighbour’s house, who wrapped them in bed sheets and promised them safety.

“We saw our parents hopelessly and helplessly wait for the inevitable to happen. Tears rolled down their eyes and quivers of fright went down their spines, but the sole relief in their hearts was that we, their children, were safe. Yet they were scared as they saw the mob that wanted to set our car ablaze to try and kill us.”

A tight fear befell over Nirmal Kaur as she recounts that fateful night, 35 years later. At the time she was only fifteen years old.

“A group of over 100 people wearing red shirts and black pants marched towards our house. Some of them carried torches. We could hear the mob questioning our Punjabi tenants who lived on the ground floor. They asked, ‘Is any Sikh family living on the first floor? Our tenants replied—‘no’.”

Still the mob persisted, asking the tenants to hand over the “sardar family”. The mob knew about their whereabouts. “They wanted to set our car on fire, but some of them suggested that they burn down the Sikh gurudwara first. After they were done looting and pilfering the nearby gurudwara, the mob left our street and marched to the next street—to our surprise.”

In surrounding localities, she recalls, the mob attacked other Sikh families, harassed the women and tried to cut the hair of Sikh boys to insult, maim, and in many cases, kill them for who they are. The mob set rubber tyres alight and threw them over the innocent Sikhs.

When asked if she still feels frightened, Nirmal Kaur says, “My mother panics till today if even the door is closed forcefully. She cannot help but cry when she is asked about these events.” She, too, feel horrified if she remembers that night.

“Those who saved us were Hindus,” Nirmal Kaur says. “My cousin sister and her children were saved by a Muslim family who stayed with them for almost a week.”

—

Whenever we think of the 1984 Sikh massacre, we cannot help but think of its widows. Perhaps the ordeal the children faced was tenfold worse. Their lives have been scarred, growing up with memories of the massacre. It has traumatised them to the core of their soul.

After the riots, many children had to abandon their education and became breadwinners for their families. In some cases, where mothers were lone earners, children had to be left alone at home, which meant that these young ones went through lonely childhoods.

Typically, women blame themselves if their young ones go astray, but these children feel differently. Many of them, who have hazy memories of the 1984 riots, confess that being denied their father’s presence and tutelage is what affected them most.

A deep sense of insecurity and the stigma of living in Tilak Vihar which is also infamously known as Widows’ Colony has impacted their lives in unimaginable ways.

Raja, now 35 years old, remembers, “Everyone would talk about their fathers at school. Before I could say anything, other students use to say tauntingly, ‘He is from Tilak Vihar, a place of no fathers’.”

It is not just about their fathers but how they were killed. Fear and apprehensions engulf such children. Especially, they fear that they may be killed any day, just like their fathers and brothers were. This incapacitates them and rules out their leading a normal life. This trauma constitutes one of the major reasons for school dropouts among the survivors of the violent anti-Sikh riots.

During the violence of 1984, all institutions—the police, the executive and the administration—who are responsible for citizen’s security failed miserably. They did not discharge their duty to prevent the violence. It was sheer perfidy. All successive Indian governments have wronged the victims of the 1984 massacre. There have been nine committees, two commissions and one still ongoing Special Investigative Team. They have filed reams of reports and studies and indictments and yet, justice eludes the victims.

For more than a decade, much has been made out of the “apology” tendered by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who is a Sikh himself. Few things need to be recalled at this stage. First, it came 21 years after the massacre. Second, the assertion of feeling regret was made during the course of a debate on the Nanavati Commission report and not as part of a pre-declared or independent effort of the government to tender an apology via the Prime Minister of the country for the 1984 massacre.

The failure in delivering justice for 1984 victims has been used to underplay and minimise other incidents of mass violence; notably, in the Gujarat riots in 2002 and the Muzaffarnagar riots in 2013.

As long as 1984 goes unpunished, there will be those who try to justify impunity elsewhere too.

For 35 years, the victims of 1984 have lived in a quagmire where hopes of justice are pulled down by incessant delays in justice. They are seeking for “closure”, for some help to go on with their lives. They do not seek to “forget” what transpired or even to stop grieving. What they seek is an end to the 35 years they have spent, frozen in an unbearably horrid moment. To them, “closure” can only come if the perpetrators of 1984 are punished. This is the sole route to go beyond the persistent recollections of the catastrophe they faced. That alone can give them some respite from the images that still haunt each one of them.