New Delhi: The Ministry of Human Resources Development has reportedly removed the provisions regarding the extension of coverage of Right to Education Act up to class 12 and early three years of early childhood education from the finalised version of National Education Policy (NEP). The final version of the education policy is likely to be sent for Cabinet approval this month.

The latest development is a significant departure from the recommendations made by a committee headed by former ISRO chief K Kasturirangan.

In the draft National Education Policy, the Kasturirangan committee had recommended, “To ensure that all students, particularly students from under-privileged and disadvantaged sections, have a guaranteed opportunity to participate in high-quality schooling from early childhood education (age 3 onwards) through higher secondary education (i.e., until Grade 12) – both today considered essential for a young person’s educational development and attainment – the right to free and compulsory education as guaranteed by the RTE Act will be extended downwards to include up to three years of early childhood education prior to Grade 1, and upwards to include Grades 11 and 12.”

The latest development comes as a setback towards the goal of achieving universal school education among all communities with the aim to reduce the staggering drop-out rates.

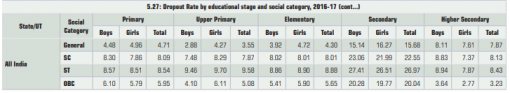

Consider this, India witnessed the highest drop-out rate in the secondary education category (Class IX and X). While the national average remained at 15.68% in 2016-17, the drop-out rates are more dismal for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Caste. The drop-rate out for SC students was 22.55% whereas the drop-out rate among the tribal students was 26.97%, a report by District Information System for Education (DISE) noted. With the lack of any universal support system like Right to Education (RTE), the numbers are bound to rise.

However, the changes have hardly surprised educationists and RTE activists alike.

Anita Rampal, former Professor at Central Institute of Education, Delhi University, maintains that the changes were bound to happen even as the mandatory conditions complying with RTE had already been diluted.

Talking to Newsclick, she said, "The draft was framed in a manner which clearly suggested that the coverage under RTE would not have had any impact on the quality of education in schools. The departure of this assurance must be read with provisions like allowing low-cost private schools which need not to abide by the basic provisions like student-teacher ratio. By allowing alternative models of education such as gurukuls, paathshaalas, madrasas, home schooling even ekal vidyalayas run by Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, the motive was quite clear to provide legitimacy to these schools where a single teacher teaches students in tribal areas."

To the question on the way forward for providing universal school education, Rampal said,"With current set of policies, I guess that there is no way forward."

Ashok Agarwal, a well known RTE activist, shared similar views. He told Newsclick, that " the policies of privatisation of education are inconsistent with objective of universalising school education. Just consider this fact, around 10 crore children are out of schools across the country. In the national capital alone, around 25 lakh children are out of school. Who are these children? They belong to the working class, SCs and STs. Now, when a policy fails to recognise the lacunae, how do we expect these children to be brought back to schools? To me, it's a question of class divide."

Apart from the RTE provisions, the final version of NEP also does away with programmes like National Tutors Programme (NTP) and Remedial Instructional Aides Programme (RIAP). RIAP which was envisioned as a temporary 10-year project to draw instructors, (especially women from local communities) to formally help students who have fallen behind and bring them back into the fold.

The draft NEP maintained that instructors would be true local heroes — bringing back students who might otherwise drop out, not attend, or never catch up. The instructors would be drawn from among those in the local communities who have passed Grade 12 (or the highest grade in school that was available in their region at their time) and who have been among the better performers in their schools.

The programme was, however, criticised by some educationists who believed that it was in line with the previous government's policies under which untrained people were hired to teach students.