Image courtesy Anne Pinto Rodrigues/ People's Archive of Rural India

On a winter day in December last year, in a tranquil, tented wildlife camp, Gond artist Mithlesh Kumar Shyam spread out his brightly coloured paintings on a large wooden table. He had arrived in the morning at the camp in Bamhni village, near Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, driving the roughly 150 kilometres from Patangarh in an old, family car.

There were trees, birds, tigers and other wildlife in his vivid and detailed paintings, and the rich mythology of his Gond community as well as the realities of modernity. “Sometimes, I paint from our folklore. This could be my interpretation of Bada Dev [‘great god’], our main deity, portrayed in the form of a bana [a three-stringed fiddle]. Other times, I am inspired by things and events from my daily life. I also paint from my imagination, even my dreams,” says 27-year-old Mithlesh.

Like other Gond artists, Mithlesh too has a distinctive style of executing the infilling pattern – a combination of dots, dashes and small curves that fill the larger shapes in a painting. On festive occasions, he tells me, the Gonds decorate the facades of their mud houses with traditional motifs that they believe bring good fortune. The wall art, which illustrates their deities, myths and legends, is known as Gond bitti chitra. “The colours we use for this are usually found in nature – green from the leaves of the semi plant, orange from marigold flower, yellow from sunflower, dark pink from rose, brown from gobar [cow dung], white from chuhi [white mud], black from black mud, and so on,” explains the artist.

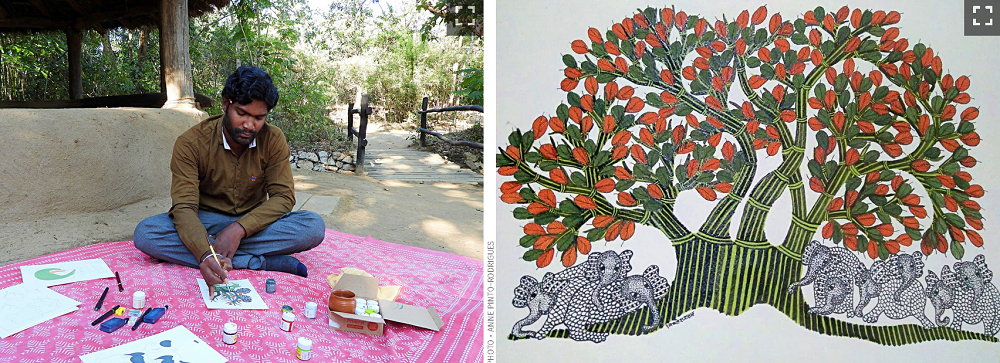

Mithlesh Kumar Shyam at the wildlife camp where he occasionally displays and sells his paintings. Like other Gond artists, he too has a distinctive style | Image courtesy Anne Pinto Rodrigues and Mithlesh Kumar Shyam respectively/ People's Archive of Rural India

Mithlesh Kumar Shyam at the wildlife camp where he occasionally displays and sells his paintings. Like other Gond artists, he too has a distinctive style | Image courtesy Anne Pinto Rodrigues and Mithlesh Kumar Shyam respectively/ People's Archive of Rural India

The Gonds, listed as a Scheduled Tribe, live across various states of central India – Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh – but mainly in Madhya Pradesh. “We celebrate both Gond [animist] and Hindu festivals,” Mithlesh says. “Haryali in August, to pray for a good harvest; Nava Khavayye in September, to celebrate the harvest; Holi in spring; and Diwali later in the year.”

Mithlesh and his family belong to the Pardhan sub-group of the Gond tribe. Once highly respected as the community’s bards, the Pardhan Gonds narrated folk tales and religious epics via song, to the accompaniment of the three-stringed bana. They preserved stories in oral form, passed down over generations. But now, many young people in the community have moved on to painting. “Today, we do our storytelling on paper or canvas, using acrylic colours,” says Mithlesh.

He has been doing this visual storytelling for more than a decade. Mithlesh began painting when he was around 14 years old, learning the nuances from his older sister, Radha Tekam, who is also an artist. The siblings have followed in the footsteps of their illustrious paternal granduncle, Jangarh Singh Shyam (1962-2001), who in the 1980s transposed the traditional Gond wall art to paper and canvas. His art came to be known as ‘Jangarh Kalam’ – 'Jangarh' after its creator, and ‘kalam’ for the artists’ pen that is used for outlining, and for filling techniques like cross-hatching. It is this art form, executed on paper and canvas, that is now broadly known as Gond art in India and around the world. (Its growing popularity poses other challenges – paintings created by non-Gond artists are often sold as Gond art to unsuspecting buyers, thus damaging the market for genuine artworks).

Top row: 'Sometimes, I paint from our folklore,' Mithlesh says. 'Other times, I am inspired by things and events from my daily life. I also paint from my imagination, even my dreams'. Bottom row: Roshni Shyam's paitings; she is Mithlesh's wife and also an artist | Image courtesy Mithlesh Kumar Shyam/ People's Archive of Rural India

Top row: 'Sometimes, I paint from our folklore,' Mithlesh says. 'Other times, I am inspired by things and events from my daily life. I also paint from my imagination, even my dreams'. Bottom row: Roshni Shyam's paitings; she is Mithlesh's wife and also an artist | Image courtesy Mithlesh Kumar Shyam/ People's Archive of Rural India

“When my granduncle’s work gained popularity, and his workload increased, he trained his family and friends from the village to assist him,” Mithlesh explains. “Soon, his trainees were working on their own paintings, and in turn, they taught others.” Today, Mithlesh estimates, there’s at least one artist in nearly 80 per cent of the 213 homes in Patangarh, nearly half of them women. His wife Roshni is also an artist. “She used to assist me initially, but now she makes her own paintings,” he says.

Mithlesh’s A4-sized paper and canvas paintings are typically sold for about Rs. 2,000 per piece, the A3-sized ones for Rs. 4,000. “It takes me two to three days to complete each artwork,” he says. But with only occasional sales, his earnings vary. Most of his paintings are sold to tourists who come to the hotels and resorts in the vicinity of Kanha National Park. A few, like the camp at which he was showing his paintings, offer space to Patangarh’s artists to exhibit and sell their work. At times, dedicated visitors and buyers go directly to Patangarh, which is reputed as an “artists’ village.”

When Mithlesh and his fellow artists go to the resorts and other venues, they take along around 100-150 paintings. The paintings of several artists, both male and female, are pooled together and shown to the tourists and other potential buyers. At the end of his day at the Kanha wildlife camp, by around 3 p.m., Mithlesh returns to Patangarh in his old Maruti 800. However, the wildlife sanctuary is closed for visitors from June to September every year, so the hotels around it also remain closed during these months.

The wall art or bitti chitra on Gond houses in Patangarh illustrates their deities, myths and legends| Image courtesy Mithlesh Kumar Shyam/ People's Archive of Rural India

The wall art or bitti chitra on Gond houses in Patangarh illustrates their deities, myths and legends| Image courtesy Mithlesh Kumar Shyam/ People's Archive of Rural India

Commissioned work is another source of income for Mithlesh – he occasionally paints murals in houses. Once, along with two other Gond artists, he decorated the walls of a farmhouse in Ahmedabad. It took them a month to complete the task, and together they earned Rs. 2.5 lakhs. These assignments bring Mithlesh much-needed additional income, but are few and far between.

On occasion, craft-promoting organisations like the Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India in Bhopal and Kalagram in Chandigarh call for his paintings. Exhibitions at sites like the state-run Crafts Museum in New Delhi are another avenue for the sale of paintings. But such opportunities too are not frequent, and they don’t guarantee sales, says Mithlesh, who was invited to exhibit and sell his art just once at the Crafts Museum, in 2013. “There have been occasions when I have sat in an exhibition for an entire month and sold only one painting,” he recalls. His largest painting, 5 x 4.5 feet, was bought in 2018 by a private patron at an exhibition in an upscale hotel in Delhi. It had taken him about a month to complete that canvas.

In some months, Mithlesh’s art fetches him Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 20,000. A good month is when he earns twice that amount. Most of his income is spent on household expenses and art supplies such as rotring pens, ink, acrylic and fabric colours, brushes, paper and canvas.

An intricate pattern of dots, dashes and curves fill the larger shapes in a Gond painting.'It takes me two to three days to complete each artwork', Mithlesh says|Image courtesy Mithlesh Kumar Shyam/ People's Archive of Rural India

However, it is difficult for Mithlesh and the other artists of Patangarh to procure the art supplies. Poor connectivity to their village (Census 2011 lists it as Patangarh Mal), located in Karanjiya block of Dindori district in eastern Madhya Pradesh, has meant long journeys to Bhopal, some 500 kilometres away – by bus for 4-5 hours to Jabalpur, and then an onward journey of 7-8 hours to Bhopal. A few months ago though, Mithlesh says, art supplies have become available in Jabalpur, around 200 kilometres from his village.

Poor roads and patchy transportation also makes it difficult for Patangarh’s artists to travel to cities for exhibitions and events, and many have moved to Bhopal. Those who remain in Patangarh usually work on their art alongside farming or agricultural labour. A few run small businesses to supplement their revenue from art. Mithlesh is a full-time artist. His family leases out their four-acre land to a farmer to grow rice, soyabean and other crops, and gets half the produce.

A couple of years ago, Mithlesh moved into a concrete house, allotted to his mother under a state scheme. He lives there with Roshni, their four-year-old daughter, and his mother and grandfather. His family home, a mud structure decorated with Gond bitti chitra, which he says is at least 60 years old, is still intact. “I hope to convert it into a museum one day,” he says.