The removal of Article 370, and subsequently 35A, was put forth by Union Home Minister Amit Shah on August 5 with a long list of explanations over why it needed to be done. Women were mentioned several times during the speech and debates that followed.

Women were assumed to be welcoming the move. News reports quoted activists in Jammu, Pandit Kashmiri women married in other parts of the country, and women sarpanches from Kashmir who were supportive of this move.

While all of them are stakeholders in Kashmir, they missed out the Kashmiri women actually living in the Valley, who are also equal stakeholders in Kashmir, and are facing the heaviest brunt of state brutality.

Article 35A allowed the Jammu and Kashmir assembly to define who permanent residents were, and once women from the state married outside, they lost their rights to hold immovable property, to work in permanent positions in the state, the right to scholarships and such other forms of aid as the state government provides.

This became particularly discriminatory for Pandit Kashmiri women who in 1990 were forcibly moved to Jammu or other parts of the country. In the State and others versus Dr Susheela Sawhney and others judgement in October 2002, the J&K High Court struck down the provision of the state subject (permanent residency) law according to which women marrying outsiders would lose their permanent resident status. Reference to the judgement came about during the hearings on 35A in the Supreme Court last January.

It had been cleared by the courts, so was removing this article from the Indian constitution really imperative, or could it just have been done through an amendment?

Women in the valley have faced the brunt of militarisation as well as militancy for decades. Neither the polity nor the administration has ever been willing or proactive in engaging with the women of the valley. And the centre, no matter which party is in power, has always failed the women of Kashmir.

Economic, political inequalities, along with gross human rights violations, a lack of human security, and a constant fear of the state acting arbitrarily has been going on for long and its consequences are always ignored, making it seem like the unsaid official approach of the state: to let things be as they are, till they are forgotten.

The use of sexual violence by Indian forces against Kashmiri women has forever been covered up giving them blanket impunity. The way in which women of this region have witnessed and experienced militarisation and sexual violence has never been taken into consideration as part of resolving the Kashmir issue.

Understanding women’s experiences of violence requires situated knowledge of their interaction with the state. Instead, the state has actively attempted to invisiblise the violence it inflicts directly on the women of Kashmir, as well as the indirect effects its militarisation has had on their everyday lives.

The history of Kashmir’s struggle is filled with instances of women being brutalised to supress the cause. On one hand the state has been prolonging the trial of Kunanposhpora, and on the other hand, survivors and their families are not allowed to gather and commemorate the anniversaries of the brutal attack.

Similar instances of sexual violence such as that of Mubina Ghani, Hasina, the rape of at least six women at Chak Sadipora in Sopore in 1992, the rape at Haran in the same year, at Gurihakhar and more recently the case of Asiya and Neelofar in 2009, are among the well known and documented cases which from time to time remain central in evoking the people’s anger.

The driving force behind protests to mark these incidents is the violence perpetrated on women’s bodies, and impunity to the perpetrators, which then moves on to everyone’s right to self-determination.

In not a single case of sexual violence has the state ordered prosecution.

While invoking women’s rights, the home minister projected a selective picture of why women were unable to realise their full rights in the state. Living in a state that has not been declared a disputed territory by the government, yet has draconian laws like AFSPA in place, contradicts the government’s claim that it is keen to make women of the state on a par with women in other parts of the country—in other words, removing Article 370 for the emancipation of women.

India’s militaristic approach to Kashmiri women has violently denied them the right to choose what they want. The state’s lack of accountability and its failure to address the issue of impunity, and provide justice to these women, has always been disguised as “the national interest” and keeping the morale of the forces high.

Most heinous crimes in the valley have been committed and covered up citing impunity under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act.

The Justice Verma Committee recommended in 2013 that AFSPA be reviewed for its legitimising violence against women as a matter of internal security. There was no follow-up or discussion of the recommendation. These concerns have been raised time and again by women’s rights groups in India and human rights bodies across the world, giving reference to CEDAW, UN resolutions 1325 and 1820, Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The point where AFSPA begins is where individual liberties end. To acknowledge and understand the meaning of justice for women living under the shadow of AFSPA would help the state recognise why removing Article 370 will never be acceptable to Kashmiri women.

These contexts are important before taking any decision on the emancipation and empowerment of Kashmiri women, because every woman has different tales of trauma and violence and the healing never happened.

The everyday experiences of women coming face to face with the army, especially in rural areas, and how these shape their social life and ways of looking at the state, have never been decoded by the state or much of the public.

One also needs to consider that sexual violence hasn’t been the only form of violence inflicted on Kashmiri women. Militarisation has shaped the ways women negotiate their space, and their roles in society and family.

It has made them the keepers of memory, who having witnessed and experienced violence, have over the years learnt to articulate their trauma in ways the state refuses to hear.

It has in places restricted their access to public life and in places thrown them out of their private sphere into the public domain, politicising their relationships.

The women members of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons is an example of how these extra-ordinary situations have thrown women into the public domain and politicised motherhood.

For nearly three decades now, their non-violent and regular protests have educated young people about the dark underbelly of the Indian presence in the valley.

Kashmiri women, from the days of Dogra rule to the present, have always found their ways to engage in politics, but what reached them in return was deadly violence, not a dialogue for engagement. Now the same violent approach is being repeated in 2019.

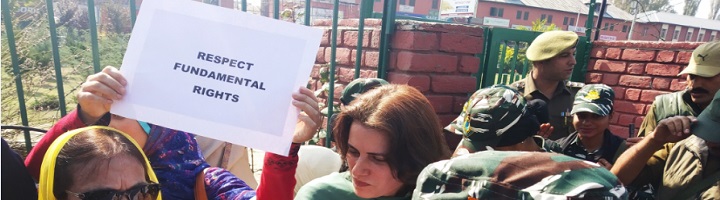

Kashmiri women have taken the roles of victims as well as agents in the ongoing conflict. On October 15 when some well-known Kashmiri women protested peacefully at Srinagar, they were met with arrests and let off only after paying fines and signing bonds that they would not indulge in any such public activity for at least a year.

India, being a party to UN resolution 1325, is mandated to involve women in peace-building and decision-making in the conflict regions. Instead the state attempted to thrust its definition of peace upon people, building peace under the shadow of the gun, arresting these women and not even considering to engage with those other women who keep protesting regularly in other parts of the valley.

Excluding women from the process of restoring peace, of making decisions, while putting them at the forefront to justify the arbitrary use of power by the state is problematic at many levels.

First and the most obviously, to exclude women from decision-making while creating the sense that it was done for them, is a colonial, macho and top-down approach that never actually benefits women.

It is the same as some other government moves which did not take into account whether women needed them, or needed them in the manner done: such as the repeated criminalisation of triple talaq, or characterising Hadiya’s marriage as love jihad.

In these examples the state postures itself as a patriarch, taking decisions for women, thrusting decisions upon them, making them believe it is the best protector of their interests.

In the case of Kashmir, if the state believed that abrogation was for women’s betterment, why not make the process of taking decisions more transparent, and seek suggestions from stakeholders at all levels?

It is humiliating for women to have their rights put at the forefront of a decision without their being party to it, and then to be arrested when they come out to publicly articulate their concerns.

Second, by making women’s rights central to the move, the central government was trying to create enemies within. Just as in the case of triple talaq and other instances the government decided it was the protector of Muslim women, in abrogating Article 370 the home minister gave a sense that women in Kashmir were suffering and needed the Indian government and laws to protect them, which could only happen in the absence of Article 370.

In doing so it created a victim and messiah dichotomy, with Kashmiri women as the victims and the Indian state as the messiah. This places Kashmiri men as the abhorred violators, leaving out the state institutions which most Kashmiris view as greater violators of their rights.

The enemy created thus was an antagonised Kashmiri male. Would Kashmiri women want the state to go after their husbands, sons, brothers, friends, or anyone arbitrarily as the state is doing now, even while it justifies its moves as protecting their rights?

Women of the region don’t want a choice between their rights and the detention of their loved ones. They want to be able to exercise rights and their agency in exercising those rights. They want answers to where their family and friends were taken 24 years back who never returned. They await closure to be able to mourn. They want answers the state has failed to give them thus far.

The fact remains that experiences of gender-based violence are common throughout the country and the world. The presence of an armed conflict adds another layer of violence and brings in another set of patriarchs and violators in the form of armed forces and militants.

No Indian state where Indian laws are fully applicable can claim to have done away with various forms of gender-based violence by justly implementing these laws. Moreover, many central laws have been implemented in J&K with its assembly’s approval, but haven’t significantly redressed gender-based violence, just as in other parts of the country.

The presence of Article 370 did not hinder the process of seeking justice structurally, unlike AFSPA which clearly violates the rights of people through its very substance, structure and the institutions—yet the government maintains it as a gospel.

If one were to assess pro-women steps taken by the government for the women of Jammu and Kashmir in the last few years, specifically since the Modi government came to power, one wouldn’t find any.

Only in May, the governor reimposed stamp duty on women buying property which had been waived by the PDP-BJP government as a move to encourage women to buy property. Women’s protests to have it rolled back fell on deaf ears because they were devoid of any political agenda, and could not be used to play to the right-wing gallery of the central government.

Navigating redressal systems in the state is complicated by the armed conflict, where the violators are often the same people women must seek redressal from. With a renewed cycle of gross human rights violations this crisis of credibility gets further deepened, and help-seeking becomes more and more distressing and stigmatising for women.

The aftermath of the abrogation has collapsed the accountability of the state, and institutionalised violence against citizens. Apart from specific gender-based violence, women in Kashmir are facing the worst kinds of human rights violations that all Kashmiris are facing at the moment.

The state is ready to treat them as collaterals or isolated incidents. But to those at the receiving end of violence, no incident can be isolated, and for Kashmiris justice delivery has long been an isolated incident in itself.

The issue of women’s rights was raised alongside the issue of returning Pandit Kashmiris back to their homes in the valley, a promise that successive governments have made and broken. This could have been done without removing Article 370, and the same is true for opening up cases against those who committed atrocities against Pandit Kashmiris during the 90s.

Pandits’ return, as per the state, is associated with ensuring peaceful militarisation and ending militancy in the region. So far as bringing in peace is concerned, the state has developed a scale for measuring peace in terms of number of deaths, and if that is to be taken as a standard then the valley is undoubtedly at peace.

But putting an end to militancy after having alienated local residents, and having pushed them to extremes, is unrealistic. Even if their pent-up anger doesn’t manifest in violent forms, the state has pitted Muslims and Pandits against each other, and further widened the divide between the two.

The sense of majority and minority created by the state will increase hostilities between the two communities.

Could ordinary people’s issues have been addressed in a better way, without embittering these two communities, and creating in both a sense of loss at different times in history? Could the ambiguity over inheritance have been done away with a constitutional amendment?

After making claims about working for women’s betterment, how can the state still exclude rape and sexual violence perpetrated by the army from its definition of violence, and evade discussions over it?

What does development mean to the women, men and children of Kashmir who are witness to the most brutal face of the state and its forces? What do inheritance rights mean to Kashmiri women when all their basic rights are undefended, and they are at the mercy of the men in power at the centre?

The state will never address these questions. It will continue to rejoice in its own narrative, using women as pawns to appease the right wing. It will go on depriving them of psychosocial and legal support.