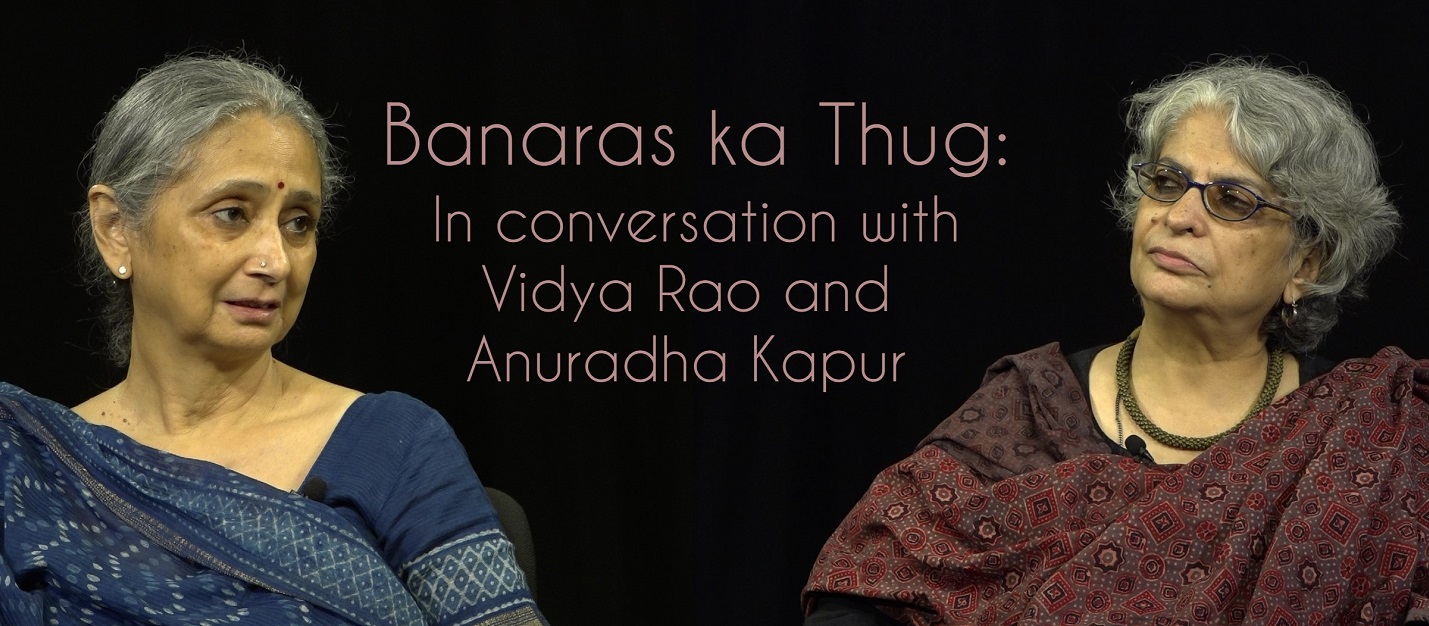

“Banaras ka Thug” is a play based on a short story by the same name by Khwaja Ahmed Abbas. The play has been conceived by Anuradha Kapur and Vidya Rao and was first staged in July this year. In this conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum, they talk about the inspiration behind the play; the secular-humanist legacy of Kabir; Banaras an inclusive space and more.

Ishita Mehta: Could you tell us a little about the play and the inspiration behind it?

Vidya Rao: “Banaras ka Thug” is a bit loosely structured, but has a lot of potential. It is based on a simple story. When we started discussing this project, I told Anu that we should tell simple stories otherwise a lot of complexity creeps in and subtleties are seldom understood by everyone. We had to edit it to make it crisp. The play is about a person who arrives in Banaras and is very confused. He asks questions which makes the viewer think of how we are living. The ways in which the city has changed from the way he imagines it. The ways in which people are divided in different ways — on the basis of wealth, religion, and so on. Not just in life, but even in death, differences are being made. And so, through this story, we look at our life, our way of living — it is a questioning, a commentary. That’s what the play is all about.

Anuradha Kapur: As Vidya said, it is a kind of a parable. It is like entering a city and by questioning, being confused, you question the very structure of the “city”. So all these things — questions about our very basic rights, are asked several times and with different angles. That was the basic structure that came into the story. The other thing that came up was — if we are to call this a story, how do we introduce a “citation” in the story. If you read the story, you find out at the very end that the protagonist is Kabir, but there are indications of that throughout the story. When we were discussing this venture, Vidya came up with a parallel text in music, to complement the story and to increase the scope and reach of the story. Because of this structure, you are exposed to two kinds of experiences — where you are listening to a great corpus of music and writings of poets which has been intercut with Khwaja Ahmed Abbas’ story.

Read more | A Social History of Thumri with Vidya Rao

IM: Kabir has a legacy of secular humanism which is also a theme in the play. At the same time, it also seems to be under assault in the current political climate of the country. Would you like to comment on that?

VR: Like Anu said, it is at the very end that we learn that the protagonist is Kabir. But when we were talking about it, I felt very strongly that we shouldn’t just use Kabir’s texts as songs, because when you only use one poet’s text, especially in this kind of situation, then it gives the impression that there was only Kabir and that he was one of a kind and an unusual situation. The rest were all different. But that is not the case. We find themes based in Kabir’s writings in many places, which we refer to as “folk music”. Or even in the ghazal tradition and in the writings of progressive poets. We recognise the progressive poets, but there are other different genres too where we encounter these themes and they are talked about in different ways, in different voices. I think one of the things we should not forget is that Kabir himself has different voices within himself, different ways of saying the same thing. In this I think it’s Kabir’s brilliance, that he spoke in different ways to different people. He speaks to people in the way they would understand as well as say what needs to be said. And you are right, it is basically humanism, caring about and understanding that human beings do and must have dignity. And if we understand this, then a lot of things follow from there. So I felt that we had to mix it and actually never make it very clear till the end because it isn’t clear until the end that this indeed is Kabir.

AK: We have also tried, as Vidya was saying, to keep it open-ended, not defining the protagonist as Kabir. Sometimes you would think that it is Kabir and then suddenly you would wonder if it is Faiz. This is the richness of citations and we have intercut it with Abbas’ story. It is the experience of various kinds of words and then various kinds of singing. And the fact that you have one bicycle on stage — the only prop that we have used — which is the basic working-class conveyance. You get to go from one place to another, and you have to work with it. In a fundamental sense, it is looking at things in life which are just about life and dignity. This brings inclusivity.

VR: I also think that bicycles are useful. It does not burden you. It is a useful thing. It gets you to where you want to go, but it’s not like your phone which will talk back and tell you that it does not understand you. It is useful but it is not taking over the realms of what is human, what is beautiful, what is intelligence, what is feeling — that is human and remains with the protagonist. It’s very beautiful and it does nice things, the cycle, including looking very pretty.

Read more | रंगमंच की दुनिया में स्त्री : अनुराधा कपूर के साथ बातचीत

IM: The play is about Kabir and about Banaras. When we think of Banaras in the current political atmosphere and in our imaginations, it has become the face of aggressive Hindutva politics. In this context, does the play also try to revive a certain image of Banaras? What is it that the play is attempting or is it attempting anything at all?

AK: Certainly, I think, because the man enters Banaras and says it’s not the Banaras I know. He sees “Varanasi” everywhere and then when he sees “Banaras” he recognises where he is. Banaras always had so many lives and that’s what’s so extraordinary about it — you cannot turn Banaras into a unidimensional space. I think that that is what has happened today. There are many people and friends who say that this is not Banaras any more. I personally believe that this is not just nostalgia. If you are aware of this subliminally, then why not think about the fact? As Vidya was saying, there are many opportunities to see the other and it functions as a different kind of place. So, it would be a kind of reminder not just for Banaras but for any city that has a history but not a single history. Take for example the saree, there are so many traditions of weaving that are not found any longer. In this sense, Banaras in the play not just stands for the Banaras that was or the “Varanasi” it has become but for all cities and places with multiple histories.VR: The weaving techniques that are attributed to Banaras have come from different places, and this is so for all craft traditions. You cannot say that they belong to one place only. They are what they are because they have absorbed from so many spaces. And it is this “mixed nature” — of cities, crafts, cultures, poetry — that creates this kind of richness and beauty. AK: Earlier there used to be something overwhelming about someone saying that something is from Banaras. The fact of the matter is that you will get different things in Banaras. Different kinds of music for instance. You will find it, it is available. And now as it is found less and less, you will have to find ways to remember it. There is also the Ramleela of Ramnagar, which is on the opposite bank of Banaras. That ramleela is completely different. It is completely craft — it doesn’t give out a message — young boys play the role of Ram. There is no “masculinity” in them. All of this is happening there. It is quite an important thing.