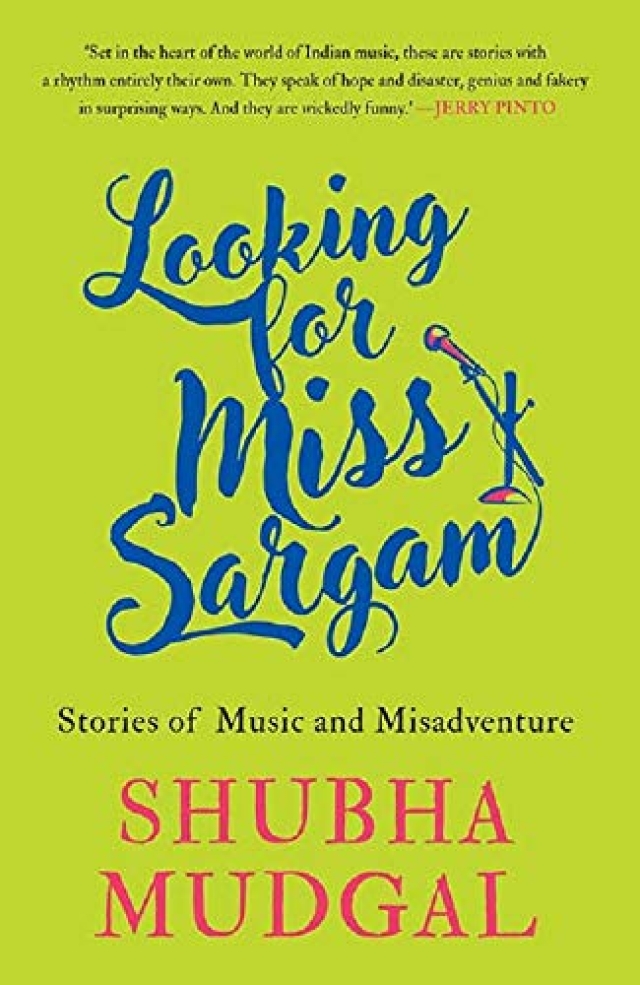

In her debut work of fiction Looking for Miss Sargam, Subha Mudgal, one of India’s finest and most original musicians has produced a sparkling collection of short stories, drawing inspiration from the world of Hindustani music.

What happens, for instance, when a cunning PR brain brings together two equally matched star musicians from India and Pakistan in a concert for peace? Or when a Hindustani vocalist, long denied a foreign tour, flies from Pune to Philadelphia? Or when a small-town music teacher and a big-city businessman team up to plan a hunt for India’s best new classical talent—and make a few crores in the process?

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “A Farewell To Music“.

A Farewell to Music

Mrigankomouli Bhattacharjee. Thirty-two. A bachelor. MBA from Harvard Business School. Coaxed into returning to work in India by his doting parents because they could not bear to be separated from their only child.

But this brief CV doesn’t quite explain why he was in the Conference Corner of India Musica that morning. So let us go back a little.

Mrigo had had no wish to go to the US to study in the first place, because he had no desire to get an MBA degree. All he’d wanted was to be a musician, a sitar player, because he was reared by his parents to love and respect Hindustani classical music. Baba, his father, could play the surbahar, and had learnt from one of Annapurna Debi’s disciples. Ma, his mother, was an expert in Atul Prasad songs. From the time he was only a toddler, Mrigo was taken along for every music festival and conference in Kolkata that his parents attended. They were delighted when they discovered that their little boy listened to classical music with rapt attention and was soon identifying raags as if he had them embedded in that curly little head of his. By the time he was five, they were certain he was gifted, and on the advice of Baba’s guru, sent him for sitar lessons to Pandit Debendra Datta, a follower of the Maihar-Senia gharana. Many of the current crop of promising sitar players were Deben Babu’s disciples and they were all serious players with a solid understanding of technique and raagdari, not the circus acts that were becoming popular. Left to himself, Mrigo might have preferred to sing, but Ma felt that since Baba played the surbahar, his son should learn to play the sitar—which she called shaytaar, in her Bengali brogue. And that settled it.

Little Mrigo started learning the sitar, and in a few years even his reticent, difficult-to-please guru had to admit— never in the boy’s presence, of course—that Mrigo’s talent for music was ‘awshaadhaaron’. Everyone knew how impossibly miserly Deben Babu was when it came to expressing appreciation, so anyone rated ‘extraordinary’ by him was certain to be prodigiously talented.

Mind you, Mrigo was also a model student in school—one whose uniform was always spick and span, whose homework was always submitted on time; a topper in his class, with a beautiful, neat handwriting, who made a habit of winning scholar badges and prizes all the time.

And of course he collected prizes and trophies at all the music and talent competitions for young musicians that were organized in Kolkata.

He was perfect, young Mrigo, and as he grew a little older, his brilliance in sitar-playing and academics seemed even to him to make up for the misfortune of large flat feet, a podgy figure that had blossomed man-boobs by the time he was fifteen, and the fact that he was a virtual marionette in the hands of his Ma and Baba. He was their obsession. They sat in stiff, restrained silence while he played on stage, but their hearts burst with pride when people applauded their Mrigo. Ma called him ‘Shaytar Shomrat’, the Emperor of Sitar, and massaged his fingers every day; Baba called him ‘Junior Robi Shonkor’ and personally clipped his nails every week.

And yet, when he told his parents, at age eighteen, of his desire to be a full-time musician, he had his first ever full-blown argument with them. In fact, it wasn’t an argument but them saying ‘No!’ repeatedly, with greater vehemence each time, and him asking ‘But why?’ repeatedly, until he found himself shouting at the top of his voice and Ma began to sob and beg Mother Durga to take her away.

Ma had an attack of migraine that evening and was in bed for a week. Baba looked grim and moved around the house in hostile silence, not saying the words but clearly blaming Mrigo for pushing his mother to a premature death. Mrigo was miserable and bewildered—they loved classical music, and they had made him love it even more, so why were they reacting like this? The mystery was solved one afternoon when he heard Ma speaking to her brother on the phone. To make sure that her cruel and wayward son heard the conversation, she left her bed and came to sit at the dining table, just outside his room.

‘Na Dada, amar shoreer ekdom bhalo nei (No, Dada, I’m not well at all),’ she sniffled. ‘I’m not well at all…Take care of myself? I shouldn’t worry? Tell me how, Dada. Tell me, no—when our future is dark. All our hopes are shattered. Our own child…I carried him in my womb for nine-and-a-half months—nine-and-a-half months! And he shouts at me! Even at his God-like father! What is our crime, Dada? We went hungry to give him the best education…and now he is a genius by God’s grace, is he not? Everyone…our entire clan has been waiting for him to make us proud. We have saved to send him to America—America, Dada, even you say that is where he should go to study further. Big companies will run after him, they will beg him to join them. Our old age will be golden, all our sacrifice…And now he says he’ll become a shaytar master! Bhogobaan! He will starve…and what of our dreams, our reputation…No, Dada, I don’t think I’ll get well…Come and meet your little sister one last time, Dada…’

It was Mrigo who relented finally, after many weeks of Ma moaning and sighing and Baba glaring at him accusingly. ‘Your Ma’s migraine has made her blood pressure dangerously high,’ Baba said to the TV screen one evening.

Read more

The priest of our old religious system

The Story of a Translation

The other side of the line of Hinduism