Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s clarion call to all Indians to “hug each Kashmiri, build new paradise”, preceded by Jammu and Kashmir Governor Satya Pal Malik’s rebuke to Union Ministers for “talking of attacks on Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK)… instead of war we can take back (PoK) on the basis of development of Jammu and Kashmir”, both beg contextualisation. Because, both remarks seemingly steer the discussion away from the bellicose rhetoric which has become the new discourse on Kashmir. However, these statements also stick out because they do not quite match the actual ground reality.

Since 5 August, entire Kashmir has been locked up, thousands have been detained, the local media has been silenced, IndiaPost has suspended postal services, courts cannot function because court notices cannot be delivered, there are restrictions on traffic movement and detentions of scores of lawyers has made accessing the judiciary an onerous task.

The internet shutdown means that the government of India’s own policies, which require internet access, cannot be availed. Local people are clueless about what is being planned for their future, over which they are neither consulted nor have any control. What they are offered is bland rhetoric about the benefits of abrogation of Article 370.

Despite the government’s claim that 20,339 schools are “conducting classes” they remain non-functional. Among other figures touted by officials is that hospitals are functioning with 5,10,870 attending Out-Patient Departments or OPDs and 15,157 surgeries between 5 August and 21 September. Moreover, since 6 August 42,600 trucks are said to have carried supplies to Kashmir. These figures are meant for Indian and foreign public consumption and not for the Kashmiri Muslims.

When a newspaper reported on difficulties faced by people to access the High Court to file Habeas Corpus petitions, soon, a propaganda barrage was launched to show how the number of detentions under the Public Safety Act was 921 in 2016 and has come down to 211. As for Habeas Corpus, 252 have been filed since 5 August.

However, what was ignored was the fact that filing of Habeas Corpus is one thing; what is important is what follows after the filing of petitions. Now, 147 cases are in the stage of admission, 85 are listed for orders and as regards 20 cases, there is no information available as to which stage they are in.

Besides, even if court were to function there are other problems which an aggrieved encounters. Postal services remain suspended so court notices which have to be issued to the parties concerned cannot be served. The High Court website itself lists “restrictions on traffic movement” as being responsible for postponements.

So, High Court began with ‘Dasti’ (personal) delivery from September 13. Difficulty is that personal deliveries do not cover everyone. Besides, in Habeas Corpus cases, dates being set for hearing are weeks ahead, whereas the very purpose of Habeas Corpus is that they require urgent handling. This relates to High Court. As for the lower judiciary, there is nothing known about whether they are operating at all.

Another sign of abnormality is evident in the fact that between 14 February and 4 August, no less than 4,150 Habeas Corpus petitions were filed. The fate of these cases remains unknown. Detentions were a common phenomenon across Kashmir even before the 5 August abrogation of Article 370 and 35A. The point is that there is no sign of relief for people in the valley of Kashmir.

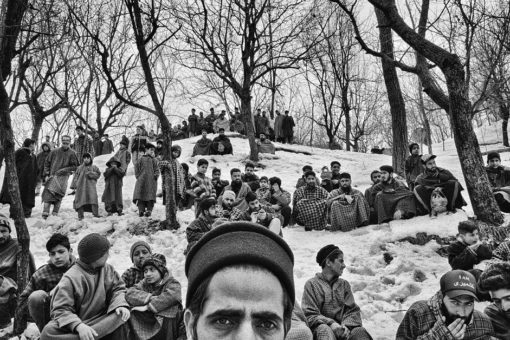

What observers see is a stupendous increase in deployment of military forces, a return of bunkers after nearly ten years, concertina wires on the roads and sports fields to basically keep children from playing sport, and reducing everyone to the status of captives whose well-being depends on the sufferance of authorities.

So what does it mean, to embrace a Kashmiri when abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A has meant that their land can be bought and sold to anyone and they have no protection over jobs? This fear of the threat of land grab is evident in Ladakh and Jammu too, where even those who welcomed abrogation have expressed deep concern over the land of natives being bought by people from outside and the heightened competition for jobs with outsiders.

In Ladakh, in response, the National Commission on Schedule Tribes intervened and has advocated Sixth Schedule status for Ladakh. In Jammu, even senior Bhartiya Janata Party leaders have spoken about the need for domicile status for locals in order to protect the land and jobs for natives. In other words, the issue of land and jobs cuts across regions and religions.

Remarkably, while the Indian government moved fast to assuage people in Ladakh and Kargil, they have taken an altogether different route for Jammu and Kashmir. First came the Army with its leaflet-distribution campaign which listed 11 benefits of the abrogation. Amongst them, land figured in a manner which provides a peep into government’s intentions. It spoke of how with central government takeover, money would flow in and land prices will shoot up.

The state administration, in a big advertisement campaign in Kashmir recently claimed that the “fears of people about loss of land and properties are not well-founded. Any landowner who wishes to sell would benefit from increased prices. There is no compulsion on anybody to part with his land. The land prices are going to change in coming days manifold,” the campaign claims. So, a people reeling under the fear of losing their land are actually being encouraged to sell their land.

Seen in the light of the above, it does appear that the carrot of “development” and restoring Kashmir as “paradise” may convince the Indian public that captives are happy being held in captivity. But fact is that even when Kashmiris are referred to in non-hostile tones, they remain in captivity, without a voice of their own, and without their concerns and aspirations taken into consideration.

The sum total of government’s pronouncements, unilateral one might add, is that what Kashmiris feel or have to say is of no consequence for authorities.

It is this that suggests that the travails of Kashmiris will not ease anytime soon. And they are being kept out of the conversation, held as captives, in order to inflict whatever plan or policy the government has in store for them. So, the “paradise” or “development” is not for locals: it appears to be addressed to Indians, now that Kashmir has been annexed. It is this fear which gnaws at Kashmiris, who have begun to believe that no matter what, they will not be heard nor their interests remain safe, because they are the adversary whose “will and attitude has to be transformed”.