Translation is not just about words, it is about carrying a culture, a history, a whole world into another language. Translations do not just bring languages closer to one another, they also introduce us to diverse modes of imagining and perceiving different cultures.

To mark the International Translation Day, celebrated on 30 September, the Indian Cultural Forum will be doing a series of posts to emphasise the power and importance of translations.

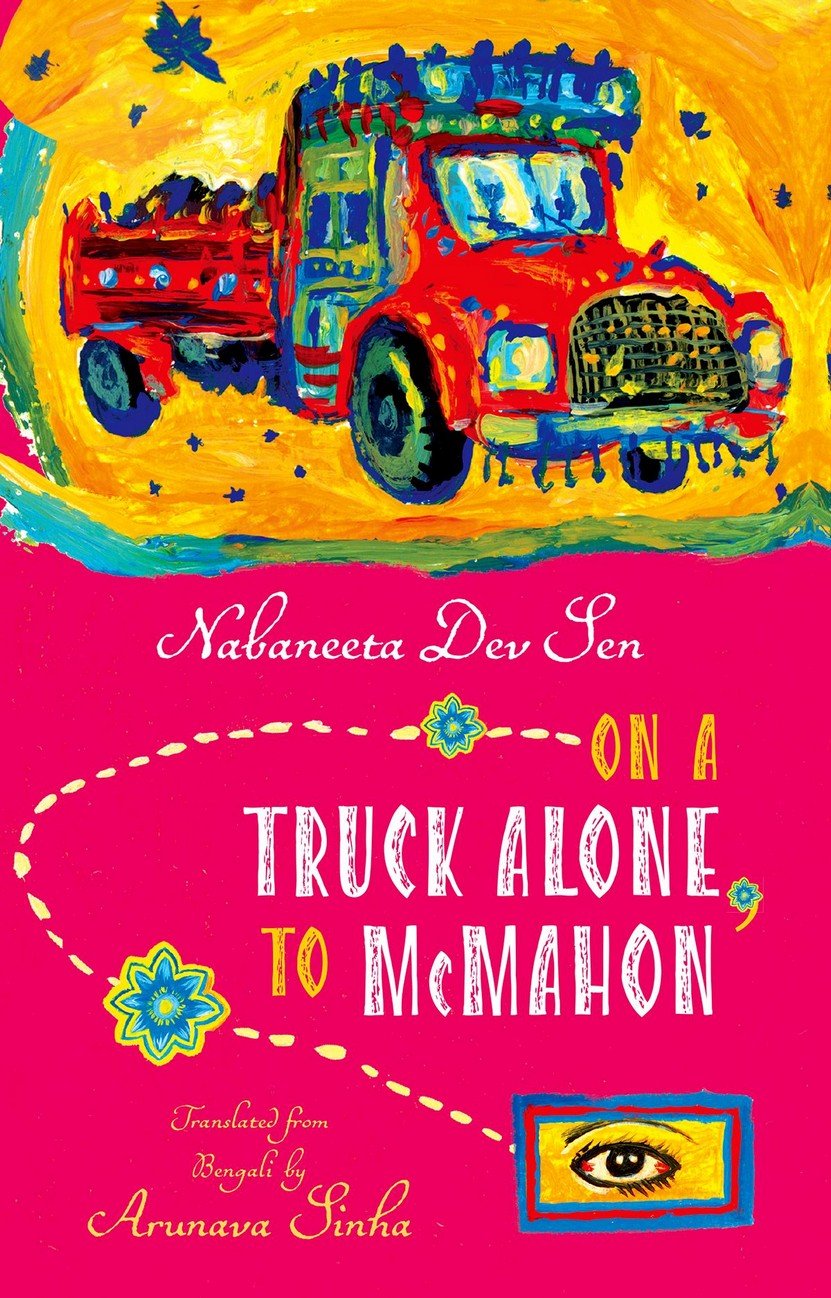

Originally published as Truckbahone McMahone in 1984 and translated into English by Arunava Sinha, On a Truck Alone to McMahon is a humorous travelogue of Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s journey across north-east India on a truck, all the way to the border between India and China called the McMahon Line. This first-person narrative captures the details of her encounters with countless ordinary individuals, their reactions to a middle-aged woman’s solo road trip and extraordinary incidents that happen along the way. Funny at times, reflective at others, this work underlines the way travel features as an avenue to liberation in the writings of many women.

The following is the chapter “Who Wants to Cross Over?” of the book.

‘A companion? How on earth will I find a companion? All right, wait, let me ask Sheela. She’s quite enthusiastic, who knows, she might agree.’

Sheela was astonished at first. Then she became very worried, and finally a little annoyed too, I suspected. What kind of madness was this on the part of her chief guest, that too in the presence of her husband and son? How could a women’s literary conference maintain its status this way? What must her husband and son have thought? Surely they’d be laughing silently. They would definitely joke about this afterwards. So she tried to persuade me not to go. ‘Why Tawang at this time of the year? It’s a very difficult road, and so cold besides. You seem to have brought only this one blanket. I have many things to attend to at home, so much work piled up because I’d been preoccupied with the literary conference. I have to supervise my son’s studies. It’s not convenient for me to travel now. And who’ll go with you? Moreover, you need an overcoat, muffler, monkey cap, gloves, woollen socks, shoes, thick sweaters, thermal underwear, and lots more. Do you plan to buy all this now? Very expensive. You must have these clothes at home already, considering you’ve lived abroad for so long. I know, of course, that writers and poets are a little eccentric, but this is too much. You don’t really need to go to Tawang urgently. Why not just spend ten days with us here in Tezpur? You could visit Dibrugarh or Duliajan instead. You have a standing invitation from Niti already. You’ll see how lavishly they do things at Oil India. They’ll keep you in the lap of luxury. They’ll look after you every moment. Besides, you’re not well. I can see how often you have to take medicines. Who gave you this idea of going to Tawang? Give up the thought.’

Here she was, taking me to Tezpur with such solicitousness that I couldn’t possibly quarrel with her. But I am prone to wanderlust. Once the idea of travelling somewhere occurs to me, I give it everything I’ve got. If it still doesn’t materialize, so be it. But I had no intention of giving up just because someone was telling me to. I consoled Sheela, ‘Not at all, you don’t have to go with me. But do you have an overcoat? And thick sweaters? A monkey cap?’

A surprised Sheela said, ‘An overcoat? I do. No monkey cap.’

‘Will you lend me the coat? You’ll definitely get it back if I’m alive.’

‘What a terrible thing to say. Why shouldn’t I get it back? Of course, I’ll lend you my coat. But I wish you weren’t going.’

‘I believe I have to go to Itanagar to get an inner line permit. Have you any idea how to get there?’

‘There’s no need to go to Itanagar.’ Sheela’s husband finally spoke up. ‘It’s available right here in Tezpur, at the office of the Arunachal ADC. I know them, I’ll get you one.’ This was manna from heaven. It was just that he was married to someone else, for I was inspired to embrace Mr Barthakur. I hadn’t exchanged a single word with either him or his son all this time. Neither of them was particularly chatty. But I had observed Mr Barthakur helping his wife tirelessly during the conference. The teenaged son had slaved away too, serving food and making endless trips in the car to help the guests get to their destinations. Sheela really was very fortunate. Homemakers do not usually get the cooperation of their husband or children when it comes to activities beyond the household. They get taunts instead. But Sheela Barthakur had pulled it off with the help of her family. Not that I saw too many male volunteers, though. The women did all the hard work.

‘It would be better to abandon the plan to visit Tawang,’ said Mr Barthakur, ‘but if you do need the inner line permit, I’ll get them to give you one.’

‘What will you do with the coat if you don’t have a companion?’ asked Jeep-babu. ‘There’s no question of travelling alone. How will you get to Tawang anyway? Where will you stay? You’ll have to make all your arrangements right here in Tezpur. There’s no point rushing to Bomdila with me. You can always take the local bus from Tezpur to Bomdila. Make all the arrangements fi rst—clear, complete, defi nite arrangements. Don’t leave before you do. What’s the use of going to Bomdila right away? You’ll just be stranded.’

I hate unsolicited advice. I’ll do as I please. So long as I don’t go in your jeep, right? So long as I don’t stay at your house. I assure you I shan’t. I’ll do it my way. I’m damned if I’m going to hang on to your coat-tails. While muttering all these imprecations in my head, what I actually said was, ‘Never mind, no need to worry about me. I’ll work something out. I’ll go if things fall into place, and if they don’t, I won’t. No need to worry your heads off. There, we’ve arrived at the jetty.’ The boat was indeed being moored. ‘There’s Tezpur!’ The cry rose from the deck.

‘Here’s my phone number in Tezpur. I’m leaving at one thirty in the afternoon the day after tomorrow. Let me know if you can make all the arrangements tomorrow.’ Scribbling his number on a scrap of paper, the gentleman handed it to me. He couldn’t have been as bad a person as I had thought. He was certainly well-informed about Tawang. I’d learnt a great deal from his admonitions, and my enthusiasm had risen. I put the phone number away safely.

Read more:

The Mysterious Poetry of the Desert

The Story of a Translation

The other side of the line of Hinduism

Talking Translation : Revisiting Anis Kidwai’s Azadi Ki Chhao Mein