Translation is not just about words, it is about carrying a culture, a history, a whole world into another language. Translations do not just bring languages closer to one another, they also introduce us to diverse modes of imagining and perceiving different cultures.

To mark the International Translation Day, celebrated on 30 September, the Indian Cultural Forum will be doing a series of posts to emphasise the power and importance of translations.

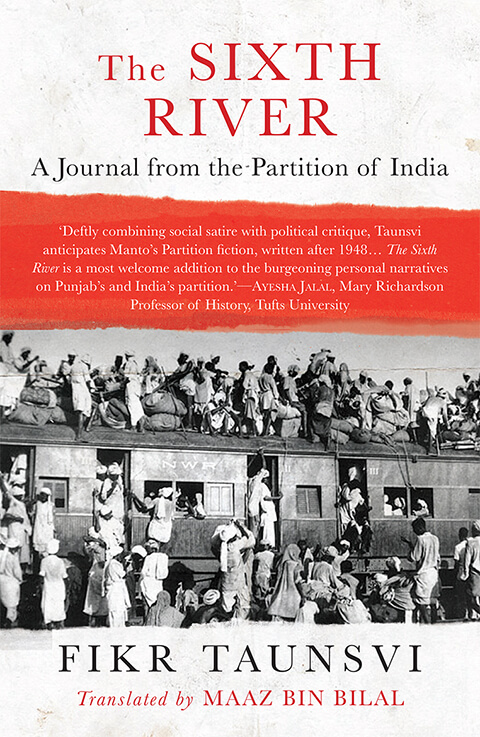

Born Ram Lal Bhatia in the town of Taunsa Sharif, then in Punjab, Fikr Taunsvi left for the cosmopolitan city of Lahore in the 1930s. Here he worked with various newspapers, wrote poetry and articles, and became a part of the intellectual circle. But when independence was announced, Fikr was faced with a new reality—of being a Hindu in his beloved city, now in Pakistan. The Partition of India in 1947 left millions displaced amidst indiscriminate murder, rapes and looting. Originally published as Chhata Darya and translated by Maaz Bin Bilal, The Sixth River is a deeply harrowing and invaluable account of the partition in the form of a journal Fikr wrote from August to November 1947 as Lahore disintegrated around him.

The following are excerpts from the introduction and the chapters “Mobbed by Darkness” and “Come, Let Us Look for the Dawn Again” of the book.

The Refugee Writes Back

Fikr’s journal is a unique text in many ways. And in subsequent sections I seek to unravel its importance, as it became the reason for me to translate Chhata Darya. The foremost reason is the importance of The Sixth River as testimony and eyewitness account of Partition by a migrant and refugee, given on their own terms. Urvashi Butalia’s seminal work that collected Partition testimony, The Other Side of Silence (1998), emphasized on how there ‘is the generality of the Partition: it exists publicly in history books. The particular is harder to discover; it exists privately in stories told and retold inside so many households in India and Pakistan’ (4). Fikr’s Partition text exists as an

independent written record by a refugee that is outside both of Butalia’s considerations, the post-event history written by Western or subcontinental scholars using archival records, and the important oral testimonies collected from refugees by not only Butalia but also Ritu Menon, Veena Das and others. The Sixth River is among the very few detailed records written during the Indian Partition but by a refugee in their own voice, and, in this case, one who was already a writer of note and an intellectual. It, therefore, retains the qualities of the reportage of events of the time, from an eyewitness and victim-participant position, but also with a literary verve.

[…]

11 August

After the sickening and soul-wearying curfew of twenty-four hours, I finally stepped out of my house this morning. All around, some languid, dull activity had begun. Layers of terror and fear had accumulated over the roads. People were stepping gingerly over these layers. Doubt and fear—fear and doubt! It felt as if everyone on the road were carrying a bomb or a knife, and would bury it in the back of the enemy in the blink of an eye. All men kept turning around. Not men but foes walked that road. Hundreds of scared and hesitant enemies had stepped out of their homes. There were no friends among them. Ambling around, I eventually started up on the street leading to my office.

It stretched through a Muslim-majority area, where there had been a bomb blast three days ago. Going through these parts was a habit for me. It was a part of my mental make-up. What else could I have done? Mental peril lay in going through the safer parts. By the time I reached my office, smoke and flames had surrounded me. A grand building right next to the office was up in crackling flames. A large crowd was present. It was a curious mass—with Hindus and Muslims. Both were trying to douse the fire together. The fire had united two cultures, two religions. I welcome such a fire, I salute it. I am ready to sacrifice millions of philosophical, learned and literary opinions and views on such a fire that allowed Muslims and Hindus a common torment on 11 August.

The first floor of the building read Bishan Das Building. The ground floor of the building housed a book-binder’s shop, where scores of workers bound copies of the Qur’an daily. Both were burning—the Hindu building and the Muslim Qur’an. Some people were trying to recover the body of a seven- or eight-year-old boy buried under a girder on the first floor. Bishan Das’s son was burning above as Muhammad’s Qur’an burnt below. God’s constitution was burning and Hindus and Muslims were dousing the fire together. A single scabbard was sheathing two swords.

I took great pleasure in the sight. Nowhere else in history had I found a reflection of such good taste. We were giving birth to a new history. I walked further. Ten paces away, in the middle of the road a decrepit, weak sixty-year-old man was sitting with his mouth open. His mouth and the side of his torso were bleeding. His open eyes, devoid of light, were staring at the sky. One soldier with a stick was guarding his life and limb. At the opposite square, shielded by five or six constables and one sub-inspector, rested the body of a thirty-year-old youth. By his side lay a bit of flour in a small bag, some of which had now spilt on the ground. The murderer had run away, because he had been in a hurry. He too probably wanted to dispose of three to four kaffirs and then take rest. He did not even wait for the police, but went away. And one soldier was saying: ‘We have told these people so many times not to go through dangerous areas, but do they listen?’

The bag of the spilt flour was unable to answer the soldier’s question.

[…]

7 November

A short soldier stopped me: ‘Hey, hey, where are you going? Who are you?’

Chaudhari, Arif, Rahi, and Sahir looked at me with a smile. A tearful melody rose inside me: ‘Life has come to a divide.’

The Gurkha soldier of D.A.V. camp, who was the protector of Hinduism, Hindu culture, Hindu rule and Hindu atmosphere, was asking me: ‘Who are you? This is a Hindu camp. Are you Hindu? If you are Hindu then what have you been doing in Lahore for so long? You should have come to this camp on 15 August. You should have…’

I bared my forearm to the Gurkha soldier, showing the blue Om tattoo I have had since my childhood. The Gurkha soldier had got the proof of my Hinduism. He had approved my entry into the camp. And Sahir, Arif, Chaudhari, Jabir and Rahi were left on the other side of the line of Hinduism and Hindutva. Those five Muslims could not step on my land. For the first time in my life, I felt intense hatred towards Hindu religion. Prior to this, I had never considered such a casual thing as religion worth the hallowed and grand sentiment of my hatred.

I became restive. For a moment it felt as if my heart were struck by a bolt of lightning and that I should not enter this camp at all. All five of my Muslim friends were looking at me from afar with their arms extended wide open. Oh! Sahir, Arif, Rahi, Chaudhari, Jabir! Stay! I am coming now! I won’t let such muddled things as this Gurkha soldier, this Hindutva line and this Hindu camp enter my life. I am coming to you. I am not going anywhere. Stop, stop. I won’t go!

And abruptly throwing my luggage aside I crossed the line drawn by the Gurkha soldier and came to the other side, where Sahir stood with his arms spread wide and said: ‘Comrade Fikr! I apologize on behalf of all of Islam, for you could not live here.’ And this statement of Sahir’s descended echoing into the depths of my soul. The corners of Chaudhari’s lips were again curling up in a way as if they were getting ready to laugh out in guffaws. But Chaudhari could not break into his guffaws. Go on Chaudhari, laugh! Do not keep this guffaw inside. Earlier, the feeling of good-health and strength was found in your guffaws. Now the guffaw that is forming upon your lips is sarcasm—at this melancholy and helplessness that prevails on this camp. Arif can neither laugh nor cry. He looks weary from excessive dejection, as if all of this is being constructed on the corpse of his hopes and dreams. All of those five Muslims—they kept sitting by my side for an hour. And kept trying to alleviate my sense of loss and pangs of separation. And the Gurkha soldier and other Hindus of the camp kept staring at us. They were rubbing their eyes and wondering how this newly admitted Hindu had developed such trust with these Muslims. A Muslim can never be sincere and truthful. He is a poisonous snake that bites on the sly. This Hindu must be a fifth columnist who is speaking to the Muslims in this friendly manner.*

*Fifth Columnist appears in English in the original.

Read more:

The Mysterious Poetry of the Desert

The Story of a Translation