Academics focus on secularism when secularisation can save the day.

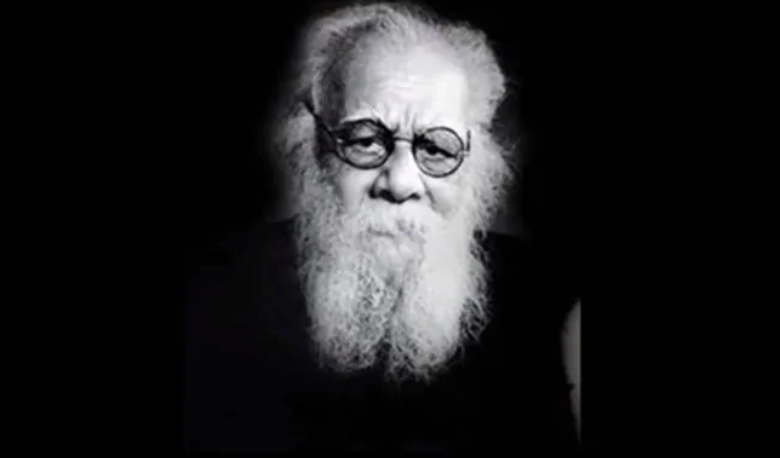

A simple query sometimes occasions judicial intervention: Does the right to freedom of expression apply merely to believers? On September 6, the Madras High Court dismissed a Public Interest Litigation filed by M Deivanayagam raising such a question. The petitioner wanted the atheistic inscriptions placed under the statue of Periyar, father of the Dravidian movement, installed in Tiruchirappalli, to be removed. He argued that the inscriptions are offensive to those who believe in a “universal god”.

The court upheld the right to freedom of expression—which is a part of the fundamental rights under India’s Constitution. It has reiterated that this right is universal and cannot be altered by numerical majority at any point of time.

Deivanayagam had also challenged the authenticity of the inscriptions attributed to Periyar. It reads as follows: “There is no god, no god, there really is no god/ He who created god is a fool/ He who preaches god is a scoundrel/ He who prays to god is uncivilised.”

The division bench of Justices S Manikumar and Subramonium Prasad dismissed the petition, emphasising that if a believer has the constitutional right under Article 19 to express her or his views on the existence of god and religion, then a non-believer has equal right to disagree and claim that there is no god.

Ramasamy Naicker, who is known as Periyar, pioneered the self-respect movement which sought equal status for the backward sections of in Tamil Nadu. He also founded the Dravida Kazhagham anti-caste movement and was a militant social reformer who died in 1978.

By sheer coincidence, a sitting judge of the Supreme Court, Justice Deepak Gupta, was delivering a public lecture in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, at around same time as the division bench was hearing the PIL on Periyar. Gupta’s speech was on the law of sedition and freedom of expression. It underlined the same aspect: atheists enjoy equal rights under the Constitution.

“Whether one is a believer, an agnostic or an atheist, one enjoys complete freedom of belief and conscience under our Constitution. There can be no impediments on the aforesaid rights except those permitted by the Constitution.”

In the present-day ambience of explosion of religiosity, where there is a growing intrusion of religion into politics and social life, receiving a fresh boost with the ascent of Hindutva supremacist forces, the judgement and reiteration of freedom of expression by a Supreme Court judge is a breath of fresh air. Obviously, such statements and rulings can boost efforts by individuals, groups and formations engaged in reinvigorating constitutional principles and values and all those who are fighting the march of intrusive religiosity.

Take the case of a petition filed by a lawyer Vinayak Shah from Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, in the Supreme Court. It has challenged the recitation of Sanskrit prayers in Kendriya Vidyalayas. According to him, doing so effectively amounts to “religious instructions for schools funded by the government”. This, Shah has argued, violates Article 28(3) of the Constitution, which says that those attending educational institutions recognised by the state or which receive aid out of state funds shall be required to take part in any religious instruction or religious worship in institutions or premises attached to them—unless they are minors and their guardian has consented to it.

This petition revolves around three issues: One, it is not right to compel children of all religions, including those from families that are atheist and agnostic, to sing Hindu prayers. Second, considering the constitutional prohibition on students being made to take religious instruction in government-funded schools, the 1,100 Kendriya Vidyalayas must not insist on holding such prayer meetings every day. Third, prayer songs obstruct the development of a scientific temper in students, which in turn Violates Article 51A(h) of the Constitution which says that it shall be the duty of every citizen to develop a scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform.

Considering the seminal importance of this issue, a bench led by Justice Rohinton Nariman and Justice Vineet Saran have referred the matter to the Chief Justice of India to be examined by a Constitutional Bench comprising at least five judges.

A few years ago, Sanjay Salve, a teacher at a Nashik school had waged a lonely struggle against the management of a school which had refused to give him a raise for he had refused to fold hands during school prayers. Salve approached the courts asking his right to freedom of expression to be protected. He said that he cannot be forced to stand with folded hands during prayers and that singing of prayers amounts to imparting religious education, not permissible under Article 28(1) of the Constitution.

A two-member bench of the Bombay High Court had ruled in his favour, saying that “forcing a teacher to do so [fold hands during prayers] will be a violation of the fundamental rights.”

These are individual examples. Efforts by rationalists in Punjab, Maharashtra, Karnataka and other parts of India also need special mention. They have built a limited base of cadres to further their cause of rationalism. Perhaps the most discussed such outfit is the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (Maharashtra Anti-Blind Faith Association), led by the legendary Narendra Dabholkar.

The Samiti is fighting superstition and spreading a scientific temperament through hundreds of its branches spread all over western India. It played a key role in passing the first anti-superstition law in 2013 in the state. Despite its limitations, the law has been widely appreciated. A report on it says that within three-and-a-half years, more than 400 cases were filed against “fraudulent godmen” under its provisions.

A draft Bill presented before the Kerala State Assembly, the Kerala Prevention and Eradication of Inhuman Evil Practices, Sorcery and Black Magic Bill 2019, has been modelled on anti-superstition and black magic Bill passed in Maharashtra and Karnataka. This proposed legislation also aims to fight superstition and eradicate cruel practices that are propagated in the name of black magic. The Kerala legislation, it is said, will advance the law even beyond the provisions of other existing laws; for example by making a provision that the government should run awareness programmes against such practices.

The struggle to limit the intrusion of religion and god into social and political life is bound to enrich secularisation, that is, the exit of the sacred from the functioning of state and society and its reconstitution on secular foundations. Scholar and activist Achin Vanaik, in his book, Hindutva Rising, underlines the need for deepening secularisation. “…the longer-term battle to defeat communalisms and fundamentalisms must be waged on the terrain of civil society, where the democratic process must be stabilised and secularisation deepened.”

It is difficult to disagree: Till date, the secularisation of civil society has not got due attention. Academic research still continues to focus on secularism and not secularisation.