When the British officially brought India under the governance of the British crown in 1858 declaring Queen Victoria as the Empress of India, the rationale provided was that the British Government would work to ‘better’ its Indian subjects. The ‘natives’ then considered uncivilized and deprived of the ‘enlightenment’ were therefore deemed unfit to govern themselves. Thus the white man’s burden was to ‘guide’ their subjects into more progressive ways of being. This meant educating Indians into Western modes of thought and stamping out what was considered to be ‘regressive cultural practices’. It is through this ‘autocratic paternalism’ that the British justified its imperialism and the banning of Sati (the practice of widow self immolation over the pyre of her husband) epitomised its success. An act that Spivak described as “white men saving brown women from brown men”.

However, paternalism as a mode of colonial rule faced rejection through the convergence of nationalist struggle and women’s movement. The hollowness of this paternalistic claim of being protectors of women was revealed by feminists and nationalists as the debate for franchise began in the 1900s and the British administrators resisted the reform stating that “social conditions of India make it premature to extend the franchise to Indian women” (Great Britain Franchise Committee). The white man’s burden was therefore limited to speaking for the women but never to create enabling spaces for women to speak for themselves.

Interesting though while the paternalist colonial project was turned on its head during the formation of a new social contract post independence, only a few years later, as the militarisation of Kashmir began, and the once colonised turned colonisers, the colonial rhetoric of paternalism too found its way back. One could always hear arguments about how India was indeed ‘protecting’ Kashmir from Pakistan and Kashmiri women from the Pakistani ‘other’. Thus, as India formalized its occupation of Kashmir by abrogating Article 370, the skeletal structure that at least symbolically granted Kashmir autonomy and remained as a remnant of India’s hollowed promise of a referendum, the logic of the white man’s burden, of doing it for their own good, consolidated itself, and crept its way back into our whatsapp groups and official declarations. Images of a saffron turban ironically blinding and muffling Kashmir and spreading across the length and breadth of the Indian map flooded social media, as people celebrated the occasion of Kashmir ‘becoming ours’. Among the various ‘rationales’ put forward for enabling Kashmir’s tryst with development is again the garb of women’s emancipation as saffron men are now proclaiming to save Kashmiri Muslim women from their men as the abrogation of article 370 will now put Kashmiri men under the jurisdiction of Indian constitution which has criminalized triple talaq for the ‘good’ of Muslim women. The fact that the appropriation of the Muslim women’s movement on the issue of triple talaq by the right wing state itself reeks of paternalistic benevolent patriarchy is something that requires separate deliberation.

There is jubilation in the air hailing the removal of article 35 A too in the name of securing property rights for Kashmiri women who would now marry outside their community. Whether property rights for women at all mean anything in the most militarized zone of the world is a question that is met with silence and whataboutery. Similarly, it is proclaimed that this move has also been to liberate queer people of Kashmir as they can now live freely in a land where homosexuality is no longer criminalised. That it is the same Indian government that uses its army to molest, rape, degrade Kashmiri women day in and day out, becomes a narrative spun by the anti-nationals as Kashmir reels under lockdown and communication blackout, unable to speak. It is also important to note that this trope of saving Muslim women have been an excuse for imperial interventions worldwide. Interventions and invasions in the Middle East by the US government too draws its justification through the ‘saving’ syndrome.

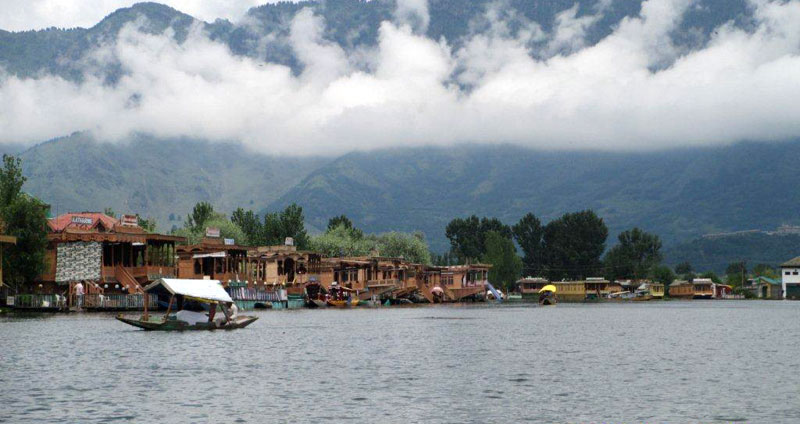

The imperial project lay itself bare through the Prime Minister’s address to the nation that declared how Kashmir is now open for development, fresh virgin lands to be conquered by the Ambanis and Adanis. We have real estate companies spinning advertisements to cater to middle class dreams of buying a house overlooking the Dal Lake, and ministers proclaiming how Kashmiri girls can now be brought as brides to balance sex ratios in Haryana. Neither is it much of a departure from the gendered notions of the nation building project, nor is it very different from the classic patriarchal design of using women as instruments of accession. The viewing of Kashmiri women as colonial conquests has historically been an ideological tool of the nationalist project. It is therefore no surprise that post August 5, 2019, Google searches have gone up for pictures of Kashmiri women and on ‘how to marry Kashmiri women’. What this article is trying to argue is that this is not just casual misogyny. We need to see this as an integral ideological tool of occupation.

Even in the process of the postcolonial nation formation project, women’s citizenship had always been mediated through kinship networks. Similarly, women’s bodies have always been political arenas used to communicate to male citizens. One might remember how during the nation building project of partition, women’s bodies were used to send political narratives to the ‘other’ community. Again, in a similar vein, post partition, India and Pakistan had signed an agreement where both the newly formed nations took it upon themselves to become the father figure of the women abducted during partition violence and mutually agreed to ‘recover’ those women and ‘rehabilitate’ them in their native state. The vocabulary of recovery and rehabilitation in this context can be read as returning Hindu and Sikh women to the Hindu and Sikh fold and Muslim women to the Muslim fold. The consent or agencies of the women in question were considered immaterial in this nationalist project undertaken to claim ownership and protect nations’ ‘daughters’. Read in this context, the process of ‘integration’ that the government promises through the abrogation of Article 370, ownership of land and marrying Kashmiri women speaks volumes of the Indian state’s colonial aspirations.

Ever since the militarization of Kashmir, India has been using Kashmiri women’s bodies as ‘semiotic territory’ through which India sends its political messages. Rape as been used as a weapon of war in Kashmir to assert nationalism. One remembers the horrifying cases of Kunan Poshpora, of Shopian, of Kathua whereupon Kashmiri women have become political anatomies for the state to inscribe their warning, to impose their hegemonic masculinity. The objectification of Kashmiri women too is nothing new in the Indian political narrative. Bollywood scripts have long set up this template of fair Kashmiri women being ‘Indianized’ through love and marriage to Indian heroes. Kashmir in our Indian imagination has thus always been the idyllic landscape to be conquered, to be owned, and Kashmiri women have been seen as instruments of accessions, as colonial conquests, whose desires, aspirations are only to be defined by those desiring.

Misogyny is therefore not a casual accompaniment of occupation, we need to recognize it as a fundamental principle of occupation, an underlying premise of nationalism. The denial of Kashmiri women’s agency, the complete disregard, dismissal of their voices, their dissent, their protests, their resistances have been necessary for furthering the case for white or rather, upper caste Hindu man’s burden. It is imperative for the Indian state to depict Kashmiri women as helpless, as being sandwiched between militants, as being oppressed under Islamic fundamentalism to make a case for occupying Kashmir. But it is also precisely the time for us to reject these narratives. We who have once refused to be handmaidens of the British empire in their colonial aspirations, we, who have clamoured for women’s agency, for choice, for right to self determination of love, of gender, we who have fought too hard for freedom, we who have always stressed ‘nothing about us, without us’, we who know what it is to be imposed, to live curfewed lives, we who have been told to forget our identities, to assimilate, we need to stand with Kashmir, with Kashmiri women. Liberation movements can never be curfewed. People’s aspirations can never be contained with militarization. Kashmiri women have been saying what they want through poems, through songs, through slogans, through mourning, through remembering, in press conferences, in social media, on the streets, in funerals, in Friday protests. We only need to listen and let them speak for themselves.

In ‘Shooting an Elephant’, Orwell had written, “when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys.” As residents of an occupier country, we need to think this through not only for the people of Kashmir, but for ourselves as well.