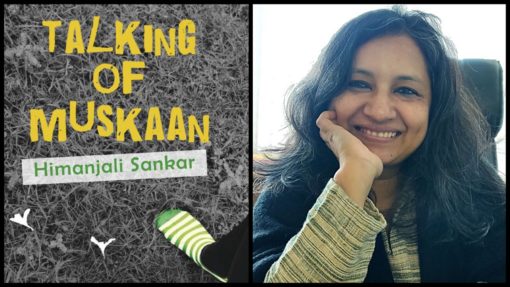

In this conversation with Daniya Rahman, author and editor Himanjali Sankar talks about books for children and young adults, the importance of writing about social issues, the responsibilities of a writer and more.

Daniya Rahman (DR): How do you find children’s books as a means to talk about issues like sexuality or mental health?

Himanjali Sankar (HS): As a writer I’m trying to tell a story, but I think it is important that whatever bothers me as a person also seep into the book. I don’t think I make the choice to talk about sexuality, communal issues or mental health, but these are just what we are increasingly aware of and bothered about. Therefore, when I choose what to write, these concerns naturally become integral. It’s not necessarily about trying to get a message across to children. These issues are important and it is crucial to sensitise children. Simply through the different characters — by showing how and what they are going through, one can make kids aware of differences. Most children grow up only exposed to the “mainstream”. It is the task of literature to show one what exists apart from what you’re usually exposed to.

DR: Does this also come out of an absence of such issues in children’s books in general?

HS: In India, writing children’s books hasn’t been around as long as Indian English books for adults has been. It has failed to grow into its own. Yet there has been an attempt to address a fair number of issues by both small and larger publishers. When I wrote Talking of Muskaan, I didn’t even realise that it was the first children’s book in which the main character was lesbian. Even with regards to mental health, we have started talking about this only very recently.

DR: Has working with publishing houses for children and young adults influenced your writing?

HS: Definitely. I was reading more of children’s writings then. The conversations I had with my colleagues helped me gain a sense of what I would like to write about and what the gaps were that need to be addressed.

My publisher is Duckbill. They were very instrumental in helping me plan the books and get me excited about writing on certain themes.

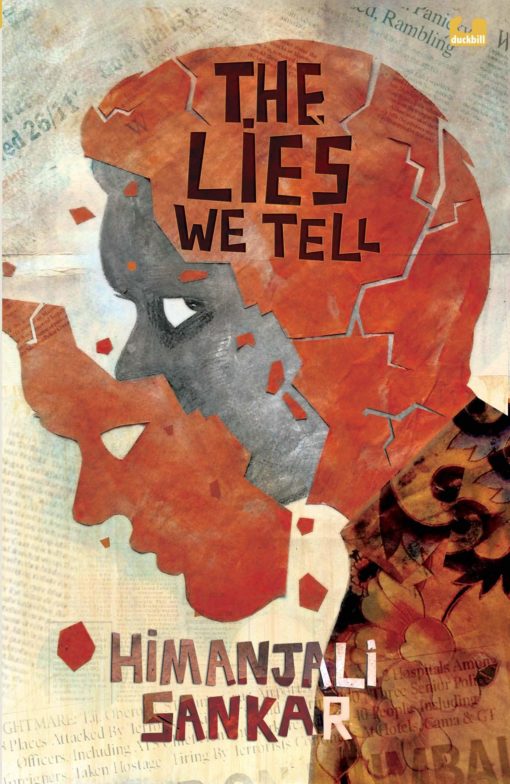

DR: In The Lies We Tell you’ve used WhatsApp chats as a form of narration. In Talking of Muskaan you’ve used narratives of her friends to tell the story. Would like to talk about your choice of styles?

HS: There were specific reasons for these choices. In Talking of Muskaan, the idea was to bring out her story through her friends’ narratives. One is a close friend, and the other not so much, but someone who would give a different point of view. So it was “talking of Muskaan”. You don’t hear Muskaan’s voice directly. It creates a narrative tension. It wasn’t a conscious choice to leave out Muskaan. When I started writing, Muskaan’s voice was very similar to Aaliya’s voice. So I decided to keep just the friends. That way she’s a little removed, but is also the main person.

With regard to WhatsApp chats in The Lies We Tell, the narrative was turning out to be very linear. The book is just one person’s voice and he’s anyway disturbed. My editors felt that the others were becoming peripheral, for it was about the main character and his angst alone. So the idea of the WhatsApp chat was just to break that up and give voice to the other two characters. The current generation is glued to social media. Even in this book, social media plays a significant role.

DR: How have the responses to your books been among children?

HS: Muskaan is older. It’s been around for a while. When Section 377 was scrapped, there was a sudden renewed interest in the book. Interestingly, I’ve had a lot of kids writing to me, saying that they were really happy to read the book and that they could identify with it; that they had not felt that with many other books. They thank me for it, and it’s just nice to hear that.

With adults, it’s been different. Most of my children’s books have been for those in the fourth or fifth standard. I used to do school visits for promoting my books. My publisher pitched for such visits for Muskaan too, but we found that schools were not very receptive to it. The principles, librarians or teachers would tell me that they were personally alright with it, but that they would rather not invite me. They were worried about the parents’ response, and thought it wasn’t appropriate for younger children to be exposed to the theme of sexuality. I find this silly, because kids are exposed to much more from what they watch and read otherwise.

The Lies We Tell got a lot of feedback. Mental health is something that youngsters are increasingly talking about. From that perspective, whatever feedback I’ve received has been good.

DR: Do you think there is also a need to write books such as these for parents, so that they could understand its importance?

HS: There are enough books for parents to read. If that isn’t opening their minds, then their minds are just not open.

DR: If not books, workshops in schools maybe?

HS: Yeah, that’s true. For kids, their biggest influence is still their parents. Whether you’re fighting your parents or accepting them, you’re still defining yourself against or through your parents. There is definitely a need to address parents, though I’m not sure how. Yes, workshops are one way or just making them aware that kids could go through certain things and feel in certain ways.

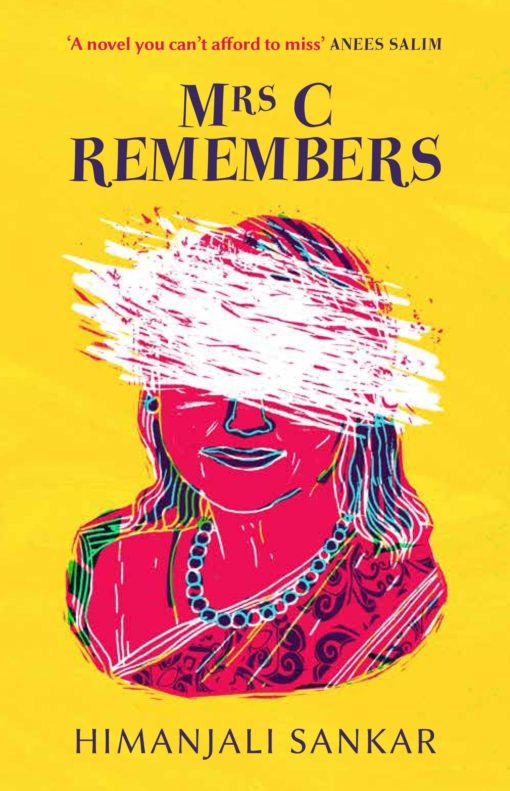

DR: How was writing a book like The Lies We Tell different from writing, say, Mrs C Remembers, which was for an adult audience?

HS: To me, they are like a pair. It’s just that the central characters are of different age groups and different genders. I wouldn’t really like to differentiate between them along the lines of children or adult books, because they’re both characters whom I felt very strongly about.

Incidentally, I thought it would be fun writing as a 17-year-old boy, so that automatically made it for a young adult audience. Mrs C Remembers is about a middle-aged woman and that made it a book for adults. The reasons for writing were the same for me — they were topics or themes that spoke to me in some way. I felt that I had to write about that.

DR: I read that Mrs C Remembers is based on some of your personal experiences.

HS: Yes, my mother has Alzheimer’s.

DR: Were your other books also influenced by something personal?

HS: I suppose, for every author there is some amount of personal and impersonal in their work. The Lies We Tell was the most removed from the personal, for me. It’s not really based on my personal experiences, but on what deeply concerns me. But even for that I had my daughter. When I was writing it, she was of that age. She is a teenager, so I would often talk to her about her friends and experiences. Mrs C was even more personal because it’s my mother I was writing about. I believe there are varying degrees of fiction and reality.

DR: Does having the personal bits help or does it make it more difficult to write?

HS: I found it easier. I wrote Mrs C Remembers quite fast, because there was nothing that I needed to consult. I’ve seen what happens with Alzheimer’s, how the mind breaks down.

In The Lies We Tell, I have talked about schizophrenia, although not explicitly. But I did talk to doctors. The research that one does when it is not personal is more, because you don’t want to get it wrong. It doesn’t come as easy, but is interesting in its own way.

DR: When you write about the personal, is there a sense of opening yourself up to the reader?

HS: It’s easier to write, but after a point, one feels apprehensive that one has said too much. It is also the family who will be reading it. I’ve mixed up fiction and facts. My extended family didn’t respond very well to Mrs C Remembers. Some of their reactions were funny. They would say things like “oh, this didn’t happen. Why has she written this?” I know it didn’t happen. It is heavily fictionalised.

DR: Do you think it’s important to write politically, especially in our current times?

HS: Yes, it is important, whether it’s writing for children or adults. That’s the point of literature. It is supposed to be for writing about the issues that bother us and to challenge the status quo. When one writes, even if it isn’t a political piece per se, their politics comes through. That’s true of children’s literature as well.

DR: Would you like to talk to us about your experience as an editor?

HS: There is politics when one is an editor as well. We are allowed to choose what to publish and what not to, but we should also make the choice to not censor them. It becomes tricky, because the tendency is to not include what you don’t agree with. You have to decide how to be inclusive and keep that balance. My own opinions are very obvious. Those aspects are complicated when you’re a publisher.