…an historian who is indefatigable in the pursuit of knowledge and prolific in its publication, and who is above all a devoted partisan of the truth. … The early history of the country has been illuminated by Professor Thapar, whom I now present, more than by almost any other scholar. An historian of that period who seriously wishes to refute accepted fictions and dispel the general darkness will need several high qualities. (From a citation presented by Oxford University to Romila Thapar while conferring on her an honorary Doctorate of Letters in 2002.)

It was 1960, when Romila Thapar, a young historian at the time, wrote a 400 plus-page monograph on Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. According to Oxford University Press, which published it in 2017, it tried to “trace virtually the entire span of Indian history.” The monograph is considered a classic today.

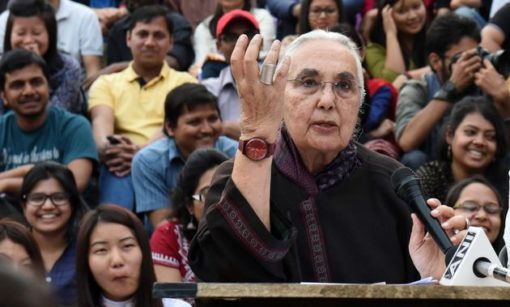

Thapar’s scholarly journey continues unabated at the age of 88. She is among the world’s foremost intellectuals, known for path-breaking work on Indian ancient history, as this interview acknowledges. Undoubtedly, her work has informed and inspired at least three generations of history students.

It hardly needs mention that Thapar has prestigious prizes to her credit for the scores of books and academic papers she has published. Twice, she declined the Padma Bhushan, the highest civilian award granted by the government.

Now, Thapar is in the news because of a strange query from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) administration, where she has held teaching and administrative positions for roughly three decades. Thapar was instrumental in setting up JNU’s prestigious department of modern history. This is the department she is still associated with as Professor Emerita after she retired in 1993. Now the university wants her CV, or curriculum vitae, so as to “review” her status and contribution as an honorary emeritus professor.

It is no wonder then that academic circles are up in arms, for they have rightly construed it as one more effort to “denigrate the teaching and learning traditions of JNU” and Thapar herself. An emeritus professorship is simply an honorary position, a status accorded to scholars an institution regards as valuable. The JNU Teachers Association (JNUTA) has said that it is unquestionably the university’s honour that scholars such as Thapar are associated with it.

Before asking Thapar to send her CV, JNU’s administration (it later said 11 others had been sent similar letters) could have checked what the American Philosophical Society, considered one of the most learned societies in the United States (US), thinks about her work. Set up by Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the US 276 years ago, this society selected Thapar as its member in June.

In 2008, Thapar was awarded the $1 million Kluge Prize for the Study of Humanity, along with the historian Peter Brown, who is also an emeritus professor at Princeton University. For the benefit of JNU’s administrators, this prize is regarded as the Nobel that honours disciplines not covered by the Nobel Prize itself. Fortunately, the possibility of being declared ‘intellectuals’—a disparaging term in the populist discourse that prevails in India—did not bother the administrators of the Kluge Prize.

The custodians JNU, exposing their anti-intellectual position, want to convey to Thapar and other scholars a message that their work beyond academics (Thapar has played a stellar role as a public intellectual who never shies away from speaking truth to power) is neither welcome nor acceptable to the present dispensation.

In an interview just before the parliamentary elections this year, Thapar had boldly stated that minorities feel alienated living under the rule of [Prime Minister Narendra] Modi. She also commented on how India’s governing party is rewriting history to justify its Hindu nationalist ideology. It is these clear-cut positions, and not the achievements listed in her CV, that seem to be the real stumbling block for JNU.

Thapar’s academic work has always been seen as ‘controversial’ by the Hindutva lobby, for her research is grounded in professional methods of investigation rather than pet theories of Hindu extremists based on extrapolation from Sanskrit texts. Thapar’s documentation of early India is at odds with the Hindutva preference for a mythical past replete with orthodoxies. To them, India is a purely Hindu civilisation; and the political advantages of this approach hardly need to be detailed in contemporary India. Regressive positions, the Right hopes, will cement its popular position even if it comes at the cost of valuable research and scholarship.

Thapar has for decades questioned the historical theories that are expounded by the Hindutva brigade. In her Communalism and the Writing of Ancient Indian History, brought out by Popular Prakashan in 1969, the Right’s flawed reliance on assumptions that date back to 19th century colonial history-writing are exposed. Again, while delivering the Athar Ali Memorial Lecture at the Aligarh Muslim University in February 2003, Thapar makes it clear why the Hindutva brigade dislikes her.

The reason is the colonial interpretation of history, which was craftily composed and propagated by the British over the 19th century. It is this history that the Hindutva brigade still goes by and readily accepts, and thus their dislike for Thapar and other proponents of modern historiography.

As Thapar said, by 1823, the History of British India by James Mill was available and widely read in India and had become a standard text of British imperialists. In it, Mill slotted Indian history into three ‘periods’—Hindu civilisation, Muslim civilisation and the British period. This periodisation was accepted in India largely without question through the 19th century (Mill died in 1836).

Thus the effects of this book lasted on Indian historiography and research for 200 years. Mill had argued in it that ‘Hindu civilisation’ was stagnant and backward, that the ‘Muslim’ era was only marginally better and that it is the British colonial power that became an agency of progress of India.

The Hindutva version of Indian history, tragically, accepts this periodisation even today. As Thapar has pointed out, the Hindu Right only changed the colours of each of these phases: It regards the Hindu period as a golden age, the Muslim period as a black and dark age of tyranny and oppression, and the colonial period as a grey zone of near-marginal importance.

What is being done by JNU is by no means Thapar’s first brush with the Hindutvadis. Nor is she the only scholar to suffer its abuse. Two decades ago, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) assumed power at the Centre and set about rewriting the educational curriculum, giving it its own chauvinistic flavour. As the project gained momentum, intellectuals and academics who were at odds with the Sangh Parivar’s view of history came under attack. Again, various pretexts were used to make their life difficult or humiliate them.

It stalled the Indian Council of Historical Research-sponsored Towards Freedom project, which was being edited by Sumit Sarkar of the University of Delhi and KN Panikkar of JNU. The National Council of Educational Research and Training also went all out to exlcude from the curriculum all influences of—in the words of the then chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh KS Sudarshan—“anti-Hindu Euro-Indians”.

In 2001, when NCERT was deleting passages from school textbooks on the grounds that they “hurt” the sentiments of one community or the other, a delegation of Arya Samajists met Murli Manohar Joshi, then human resource development minister, and demanded that Thapar and historians such as Delhi University’s RS Sharma and Arjun Dev of NCERT, be arrested. Joshi had reiterated time and again his pet thesis that “academic terrorists” are more dangerous than armed ones.

Manufactured controversies, such as demanding Thapar’s CV, also remind one of the malicious campaign of Hindutva acolytes in the Indian diaspora, who launched a vitriolic campaign in 2002 when she was honoured by the US Library of Congress. The Library wanted to appoint her as its first Kluge Chair of ‘Countries and Cultures of the South’.

While this honour was welcomed by serious students of history, Right-wingers found it “a great travesty”, and gathered over 2,000 signatures to demand that it be revoked. Political commentator, late Praful Bidwai, had then argued at the time that the campaign represented the “rebirth of McCarthyism.”

The matrix of political conditions in 1950s’ America and present-day India (and the outlook of many in the Indian diaspora) is similar. Hindu nationalists, both in India and abroad, are sensitive to India’s position in the world and see themselves as fierce defenders of the Indian nation against ‘dangerous’ elements, typically constructed as Muslim and also at times as communist/Marxist.”

Bidwai’s was a fitting comparison, for the American conservative had denigrated his political and ideological opponents by fostering deep-seated religion-led suspicion of left-wing ideologies. He had advanced a powerful and dangerous cocktail of nationalism in the US, which was grounded in so-called Christian values, whose hallmark was unquestioning support for the conservatism and its political reflections and institutions.

Clearly, the more things change, the more they remain the same.