Those affected by the communication lockdown in Kashmir the most, are journalists and the media organisations they work for. At the moment, there is a tussle going on in the Valley between Indian and international media. While Indian television channel reports show the local populace in Kashmir as happy with the decision of the government to abrogate the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, the international media has been showing ground realities, such as the curfew, the protests and the clampdown.

In this tussle between these two media giants, it is the local Kashmiri media whose voice is being muzzled. It is they, the local media outlets and their reporters, photographers, and other staff members, who come in the direct line of fire from the corridors of power.

“We have not published since the clampdown on August 5. We have no contact with our staff members either,” says Shams Irfan, an associate editor at Kashmir Life. He says that most staffers of Kashmir Life live in North and South Kashmir. There is absolutely no way for the office to contact them and vice-versa.

Many working journalists compare the present situation with the mass unrest of 2016 and find the present situation worse. “We used to work regularly in the 2016 unrest, but not anymore. There is no internet, so all the online breaking news has come to a grinding halt. Even if we somehow manage to get access to the internet, no officials come on record to confirm any news. So, we thought it would be better to suspend our online section for the time being,” an online editor of a local daily says.

Many of the journalists interviewed did not wish to be identified from fear of reprisal or arrests.

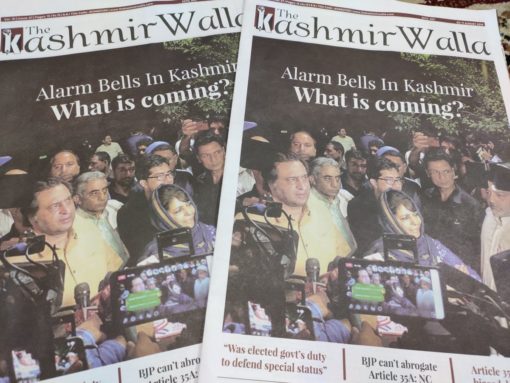

Another local weekly, The Kashmir Walla, put out its last issue on August 4. Thereafter, it has not been published. “Our website is down since the last 14 days. We have no contact with our staff members or designers. Our printing press has also run out of raw material,” says its editor, Fahad Shah.

Shah says if any of his reporters file a story it will be sort of “incomplete” as their movements have been confined to Srinagar city. “We have limited access to information. There is no way we can contact officials to confirm any incident.”

The 'Media' Centre

Although the authorities have established a media centre at a local hotel in Srinagar, many journalists hesitate to visit it and file stories from there. A total of five desktops have been established for the close to 200 working journalists in the city. At present, Kashmir has also been stormed by New Delhi-based journalists. This has made it even more difficult for local reporters to get their hands on the few desktops available.

“I have not visited the media centre since it was established. It is very difficult to work from there due to the heavy rush of journalists,” says local journalist Junaid Kathju.

Many journalists have to travel from North and South Kashmir to their office headquarters in Srinagar in order to deliver their footage or photographs in person.

“I travel from Pulwama, South Kashmir, every two days in order to deliver photographs and video footage at out office in Srinagar. The government and security forces do stop [journalists] while [they are] travelling to Srinagar but [they] only check the identity card and allow us to move,” says photojournalist Nissar-ul-Haq.

Journalists also say that the internet should at least be allowed to media organisations so that they can verify news and kill rumours. “We cannot operate from the media centre because it has a limited access. The authorities should at least give [full internet] access to the media. It will kill the rumours that are floating massively at this time in the Kashmir valley,” says Fahad Shah.

In the 21st century, supposedly a technology-driven era, the people of the northern parts of J&K are going through the worst communication lockdown that the region has ever witnessed. People here say that such harsh measures were not even been witnessed during the active conflicts in Syria or Iraq.

“When the wars in Aleppo and Homs in Syria were at their peak, SOS messages from the Syrians still used to trend [online]. Similarly, when the war in Mosul was raging in Iraq, once again, SOS messages could be seen on Twitter. Internet services were not snapped even in those active conflict regions. In Kashmir, we are observing the worst communication gag in the last 30 years,” says a local media person from the Bagh-e-Mehtab area of Srinagar, who did not wish to be identified.

This person says that a multiple-tier communication gag has been imposed in the Valley. “First, there is no mobile service. Second, the internet has been blocked. Third, landline phones are dead. Fourth, the inter-person communication has also been gagged because of the curfew-imposed across the Valley,” he adds.

Not Just Journalists

Employees from far-flung areas in the Kashmir Valley are also finding it difficult to communicate with their families at home due to the unprecedented lockdown. “I am not able to speak with my family members. There has been no contact with them since I have joined work after the Eid holidays,” says Bilal Ahmad Bhat, who works at a local shop in Srinagar city.

Bhat, a resident of Hajin area of North Kashmir, returns to his native place during the wee hours on weekends to meet his family. “During the 2016 civil unrest, I was able to talk with my family since the mobile phones were functional but today the situation [of complete blanking out of communications] is worrisome,” he said.

Bhat says he has to travel a minimum of 80 kilometers on weekends just to meet his family in Safapora area of Hajin in Bandipora district of North Kashmir; a journey he must make if he wants to check on their well-being—and they his.

The doctors in Kashmir valley have also been on tenterhooks. To reach their hospitals and attend to their patients has been next to impossible after the communication gag. They are unable to reach their hospitals on time.

“My mother is a doctor at a primary hospital in Srinagar. A few days back [Friday morning], an ambulance driver came to our home with a patient’s details written on a piece of paper. It was sheer good luck for the patient that my mother was able to reach the hospital despite these curbs and saved the patient,” says a resident of the Nigeen area of Srinagar.

The same resident says that he finds the curbs in Kashmir unprecedented. His sister lives in Bengaluru and he has not been able to contact her for two weeks. Some relatives visited his home on Eid but they have not seen them thereafter.

People in Kashmir have resorted to old means of communication such as visiting the homes of relatives or friends in person to know their whereabouts.

“When you see your friends and relatives in person only then do you stop worrying about them. If you don’t see them, at least twice a day, you start getting worried. This need for physical confirmation is a must in Kashmir these days,” says a student who lives in the Rafiabad area of North Kashmir.

He says that locals have to ask “ten different people at ten different locations” about the whereabouts of their friends or relatives, as they strive to pick up any reassuring information about their loved ones.