“It shall be the duty of every citizen ‘to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”

[Article 51A(h) of the Indian Constitution]

“I shot him twice”, says Sharad Kalaskar, one of the two prime accused in the assassination of rationalist Narendra Dabholkar, about the act. Kalaskar further elaborates the two shots – one in the head and the other, right above the eye – in his confession to the Karnataka Police. Assassinated by Kalaskar and Sachin Andure on the morning of August 20, 2013, Narendra Dabholkar was a medical doctor and the founder of the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (MANS), a group committed to fighting superstition and black magic in the state from 1989.

Dabholkar made several attempts to bring about an anti-superstition law in Maharashtra. Under his supervision, MANS drafted the Anti-Jaadu Tona Bill (Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Ordinance). The bill was opposed by the BJP and Shiv Sena, claiming that it was against Hindu culture. However, a day after his death in 2013, the bill was approved as an ordinance by the Maharashtra government. MANS has also spearheaded the campaign against polluting water bodies by the immersion of Ganesha idols in them during festivals, against godmen, astrology and other superstitious beliefs. Right before his death, he and the group were involved in an intense campaign against superstition and blind faith, with rallies and press conferences.

Dabholkar, part of the country’s pro-science and scientific temper movement, was one of the three rationalists who were murdered one after the other around the same time. Communist leader Govind Pansare in Mumbai and academic M M Kalburgi in Karnataka, were shot dead for similar reasons in the following years.

These are to be seen as attacks on reason and science in general, in a country which has had a strong philosophical streak of materialism and rationality as part of its history. Not to be seen as isolated incidents of violence, they are a part of a concerted effort to attack India’s scientific temper. Their attempts at promoting science and scientific thinking were in opposition to the narrative of the current regime, which one the one hand unleashes violence on those who work towards an inquisitive society and on the other, people at the helm of affairs, including the prime minister, produce unscientific and ahistorical claims about the country’s past. Furthermore, we have the country’s most important rocket scientists falling at the feet of godmen and astrology before each of their scientific ventures.

At six years since Dabholkar’s assassination, his death anniversary is commemorated as National Scientific Temper Day in India. Today, 20 August 2019, the Indian Cultural Forum too joins the nation in remembering this giant of a rationalist, in an effort to also develop science, rationality, and the spirit of scientific temper, a Constitutionally ordained duty of every citizen.

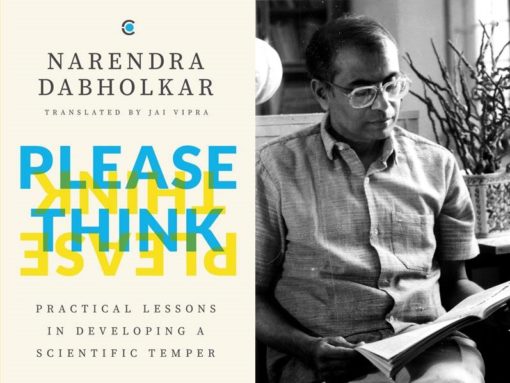

The following are excerpts from the chapters “Scientific Temper” and “Religious Inquiries and Rationalism” from Please Think: Practical Lessons in Developing a Scientific Temper by Narendra Dabholkar.

Image Credits: Amazon|The Caravan

Possessing scientific knowledge and developing a scientific temper are two different things. A person who has studied science is more likely to develop a scientific temper than someone who has no knowledge of science, but there is no guarantee that she will do so. Scientific thinking requires independence of thought, a faculty which inheres within a person’s value system. Thus, mere intellect cannot help develop a scientific temper. A person can be highly intelligent and yet incapable of independent thinking, while another person of average intellect could have a keenly analytical bent of mind.

In other words, acquiring a scientific knowledge is a function of someone’s intelligence but developing a scientific temper is a function of their values. In the same vein, the notion that common people lack the ability to internalise scientific thinking is false. In fact, it is much more difficult for such people to internalise the teachings of religion.

Certain people who possess a scientific temper also follow superstitious practices. They are either insincere or struggling to live in the way they want to. Perhaps they do not want to detract from their well-wishers. Whatever the case may be, they cannot be held up as examples for the failure of scientific thinking. We do not label pious believers as irreligious just because some other people use religion for their beliefs and their deeds. However, the truly scientific person strives to bridge the gap between their thoughts and actions.

Scientific thinking saves time, effort and money. There are only two options before us if we want to solve our country’s problems: we can be slaves to tradition or we can think scientifically. Our long history complicates this choice; the hold that tradition has over us as a people is agonising. In Indian social contexts, it is tough to adapt old beliefs, habits and institutions to changing situations. Scientific thinking helps us determine the magnitude of such changes. And a scientific temper teaches us that no matter how glorious our past, it cannot solve the questions of a completely different time – the present or the future.

A convenient merger of slavery to tradition and scientific thinking is even more dangerous. For instance, we sing the praises of scientific thinking everywhere, from our textbooks to our Constitution. But the Notable Research awards of the National Science Congress go to heads of institutes of revelatory knowledge or to chartered accountants who write essays on astrology. The Science Congress does not feel the need to correct these errors even though several venerated scientists have objected to them. No one sees anything absurd in a governor who performs a prayer ceremony to propitiate the rains, or in prime ministers and presidents who, while ushering India into the twenty-first century, also fall at ring-producing Satya Sai Baba’s feet.

If we incorporate scientific thinking in education, our children can be taught to combine and make sense of various experiences, and to derive conclusions from them.

[…]

How do religious beliefs regulate everyday life? Many traditional ceremonies, rituals and practices in society, such as weddings, inheritance or adoption, are legitimated by religion. Private and communal prayer, fasts and vows are all religious inventions. Most of these observances are tied to the notion of an afterlife. Morality, including the concept of virtue, non-violence, truth, renunciation and stoicism, is also taught as a part of religion. Religious teaching , in addition, includes certain conceptions of the world and man’s place in it – usually anthropocentric ones. It also propagates its own brand of sociology and its own theories of social organisation.

Traditions and rituals, and moral and sociological theories are not separate parts of religion. Religion is created by the very interaction of these concepts. And thus all of this ‘religiosity’ has seeped into society, with considerable impact on the people holding these beliefs.

What does our anti-superstition thinking reveal about religion?

These rituals can be exploitative and meaningless. Until recently many people believed that if a girl did not marry before a certain age, her parents would be condemned to hell, and that the doors of heaven would close for them if they did not have a son to perform their last rites. A huge amount of rice is thrown over the bride and groom during the wedding ceremony. In Maharashtra alone, fifteen-twenty lakh kilos of rice are wasted every year in this manner, but even raising this issue is considered blasphemous. Daughters are ‘donated’ in a kanya daan as if they are goods, and this degrading practice is seen as a matter of pride. A widowed woman is kept away from her own son’s wedding for no fault of hers. When a family member dies, people coop themselves up inside their homes for a twelve-day period of mourning and feed the whole village on the thirteenth day, regardless of the debt they incur. All these beliefs and practices are products of religion. In the Muslim community, triple talaq makes getting rid of a wife very easy. Sometimes couples cannot adopt even if they are incapable of having children. Every religion calls a man’s wife his ‘other half’; not one supports the woman’s claim to half her husband’s property. Religion pervades every aspect of life; this is the reason our movement needs to raise questions about it.

Which religious rituals should one follow? How does one please deities? How does one ensure happiness in the afterlife? These are personal questions for a believer, and religious individuals have the right to them. But what if, in pursuing religious goals, man is blinded to reason? Should we then respect his actions because they are religious?Should we not denounce them when they are inhuman? People have been known to run at the stone walls of temples, breaking their skulls on collision, simply to fulfil vows they made to God. They stab themselves in the back with a sharp knife or cut their own foreheads with a rusty one, tie themselves to a bullock cart which drags them along with it all day, tear open the sacrificial goat with their bare teeth, bathe their hands in buffalo blood and imprint it on the temple walls, walk on fire and roll about in the dirt around the temple. Less horrifically, they are constantly preoccupied with their aartis or namaz, and agonise over how many times they should recite the gayatri mantra, how severely to fast or whether to finish eating before sunset. People have a right to perform these rituals, of course, even if others find them pointless. Likewise, other people have a right to analyse and criticise them.

When a manufacturer of sweets donates tens of thousands of sweets to a Ganapati idol, should this act be condoned as freedom of worship? Is it acceptable for lakhs of people to gather to perform a yajna for world peace? Is the pouring of hundreds of litres of milk, ghee or honey on the ascetic Bahubali’s idol, in consonance with core religious values? Are meaningless, outdated fasts an essential part of religion? A banyan tree provides shade to a weary traveller but it can also fall and kill people when it is old and weak. How does tying a thread to a branch of this tree help increase one’s husband’s lifespan? What is the link between observing the Goddess Hartalika’s fast and acquiring a good husband?

One story that our society cannot accept any commentary on is the legend of the Satyanarayana puja. This is described in the Skanda Purana in two parts, which implies it was written around 300 CE to 400 CE. The purana says that Lord Vishnu prescribed this puja to Narada Muni as a way to earn the favour of the gods with minimum effort and money. Narada then narrated it to Suta Maharshi, who told it to Shaunaka Muni. The entirety of Hindu society is encompassed in this story. It characters include a Brahmin, King Tungadhwaj, the merchant Sadhuram and a woodcutter. These four represent the four castes of the varna system.

Sadhuram is a rich merchant. The merchant class, desirous of both preserving and increasing their wealth, is inclined to try and reap benefits from minimum investment in religious rituals. Therefore, while others in the kingdom observe the Satyanarayana puja once a year, Sadhuram is instructed to perform it every month.

The story openly uses the human motives of greed and fear to insist on the observance of this ritual. The woodcutter complies, and earns twice as usual on the day he performs the puja. Kings are unlikely to be tempted by such gains, so Tungadhwaj refuses to perform the rite. As a consequence of divine retribution, he loses his sons and risks losing his kingdom. Once he buckles and performs the puja, his former glory is restored. The merchant Sadhuram is shown to be alternately tempted and threatened. Among other things, he is accused of thievery and is thrown into prison, and eventually all his wealth disappears. Needless to say, everything is resolved when he finally performs the Satyanarayana puja.

As this story illustrates, this is a prayer that is performed purely for personal material gain. There is no element of alleviating human suffering and granting prosperity to all, as Vishnu is supposed to have promised in his narration to Narada. The saint Gadage Maharaj used to ridicule the story of Satyanarayana puja in front of assemblies of thousands. Indeed, rational people should not believe in or condone such rituals for obvious reasons, and religious people should balk at taking such an unabashed shortcut to personal well-being and gain.

Yet, most people simply acquiesce in such observances. This is akin to keeping your brain aside and participating in a meaningless ritual. The Satyanarayana prayer actually includes the verse which claims that the Brahmin was born out of Brahma’s mouth, the Kshatriya from his arm, the Vaishya from his thigh and the Shudra from his feet. How is this acceptable? We either accept the Indian Constitution or we accept this verse. Do we know what we are agreeing to when we nod silently as the priest chants? Is this ignorance or cognitive dissonance that is being cleverly exploited by religion?