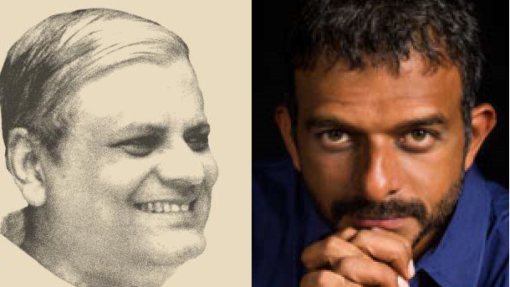

On Sunday, June 16, the second memorial lecture for veteran editor Neelabh Mishra was held at the Jawahar Bhavan in New Delhi. He would have turned 59 this year. Remembered as “a selfless mentor, a principled fighter and a true liberal”, Mishra’s final stint was with The National Herald. He passed away in February 2018 following an illness. The event was chaired by poet Ashok Vajpeyi and Karnatik musician T M Krishna delivered his lecture, “Between the Note and the Word”.

He began with the question, “What is the concept of perfection in pitch?”, and steered the talk towards the structural, aesthetic, sonic, social, cultural and semantic nature of “rightness”. Speaking and sometimes singing, he elaborated upon the histories and layers of influence that have shaped the Karnatik music of today. Despite notions that what is “classical” is standardised, “ragas are like humanity”, Krishna said. “They have the markers of centuries. It has a history of who handled it, but also has a history of who didn’t.” Appropriation, exclusion and ownership are critical factors. The “anyasvara” (the svara that doesn’t belong; the alien one), he explained, was originally sung by the devadasis. While the devadasis have been kept out, their music has become canonical.

This led to discussions on propriety, what is believed to be “correct” and “appropriate” and the notions of “purity”. Such ideas create linguistic frictions as well. The hierarchy of languages and biases within a language exist in the Karnatik music field. Songs used to be and even now are dominantly composed in Sanskrit or Telugu. But in the early 20th century, the Tamil Isai Movement backed by non-Brahmin privileged castes and funded by the well-to-do Chettiar community, supported compositions in Tamil instead. It triggered cultural feuds including conferences and meetings reported in The Hindu and heated Letters to the Editor, published by the then Madras Bureau. One such archived article that TM Krishna shared with The Indian Cultural Forum, reads that the last few years “have witnessed very marked changes due to the influx of the so-called Hindustani tunes from North India. They have been popularised by the talkie and the radio and had invaded our homes much to the detriment of classical Carnatic music. There was no conflict between pure Carnatic music and pure Hindustani music; the conflict arose only when the cheap mettus passing muster as Hindustani tunes, began to influence even Vidwans and composers.” These were the words of speakers at the Ranade Hall, Mylapore. Under the title “Lowering of Standards Deplored”, the reporter further registered the complaints made at the meeting which continue with similar petulance: “… the over-enthusiasm of advocates of Tamil culture to oust compositions in other languages all together from the field of Carnatic music. He [TL Venkatarama Aiyar] was second to none in his desire that Tamil compositions should be encouraged and popularised. But he would plead here for a recognition of the fact that there were very few compositions in Tamil which could lay claim to the same technical and aesthetic perfection …”

This obsession with “purity” that has an almost eugenic quality to it, is both disturbing and factually incorrect. These only reveal entrenched prejudices regarding “pedigree” – a dangerous fancy to harbour and it is fanciful. The belief that traditions, especially in the arts remain unchanged is laughable. In that respect, TM Krishna’s speech also touched upon the instances where social “rightness” has to take precedence. Referring to a certain operatic composition, he spoke of the many deviations that have occurred over time. The song includes the term, “parayan”, a humiliating pejorative for the leather-working, dalit sub-caste. KV Naryanswamy replaced “parayan” with “ezhai” that merely means “the poor”. This created a curious situation. While the move to replace the word was the socially correct thing to do, it impacted the song structurally, Krishna pointed out. The alliteration on the “ra” sound is lost. Alliterations are important to Karnatik music. As a way of resolving this conflict, the singer himself has instead chosen to use the word “naranin” when he performs the composition. “So the aesthetic and linguistic and social issues are tackled,” he said, speaking to the ICF.

During the lecture, he also talked about including other such interventions in his practice. On several occasions, TM Krishna has also collaborated with poet and author Perumal Murugan. Murugan is known for his “colloquial” use and masterful command over the Tamil language and his deep understanding, love and empathy for the Kongu Nadu region of Tamil Nadu that he often writes about. One of the kirthanais that he wrote for TM Krishna to perform is on the irrigational crisis in the region. It talks of the farmer’s desperation as the land turns as arid and unyielding as a “bald rock”.

The song referred to below can be heard from 46:27 minutes

The song has the word “saami”, a generic term for referring to a deity. As TM Krishna explained, the habit of saying “saami” or “swami” is a marker of caste. Only Tamil brahmins use the Sanskritised “swami”. Others normally say “saami”. That it is sung as “saami” is a deliberate detraction within the setting of a brahmanical stronghold in Karnatik music singing. “They don’t say Nataraja, they say “Natarasa. So how much, as a musician, am I sensitive to this idea of meaning and what it conveys? When changing the syllable and the sonic structure, semantics may say they both mean exactly the same. They don’t mean the same.”

Referring to the introduction of the three language system in the National Education Policy (NEP) 2019 draft, he said that the issue of language and hierarchies within have taken on fresh relevance now. The original draft made Hindi compulsory in non-Hindi speaking states. Tamil Nadu, which has a two-language system in schools was at the forefront of protesting against this move. The state already has its history of fierce anti-Hindi agitations in the late 1930s and again in the 1960s. While a revised draft has dropped the lines about compulsory Hindi following the row, it has still not wavered from the original position on three languages. Those opposed to the move have been critical of this, alleging that this is a “back-door” left open for enforcing Hindi regardless of non-Hindi speakers’ sentiments.

Krishna also spoke of those who are committed to supporting art forms that are considered “folk”. The koothu music, for instance, has gained a form of popularity today but is traditionally funereal work left to dalits. Even now most will use the terms “garish” and “crude” to describe it. Referring to people who claim to be liberal and progressive, Krishna said that they too still talk about certain cultures using such words when they can “safely” admit to those thoughts. He proposed that this disconnect comes from something fundamental that each of us is conditioned to. Even if we choose a particular position based on social justice, there is an innate inability to identify aesthetics against this conditioning.

Referring to the McGurk Effect, he asked, “Can everything but the sound, determine the sound?” He talked about how, Professor Lawrence Rosenblum, through a simple demonstration shows that “the speech brain” just takes in the information that it wants to hear and “it doesn’t care what outside knowledge you bring to bear.” Our effort then, he suggested, is not just towards political or cultural correctness, but “to find a way to negotiate the cultural ugliness within us.”

He ended with a compelling point. “Many people ask me the question, why do you write and why do you speak, can’t you just sing?” In the context of the lecture’s title, “Between the Note and the Word”, he said that question has particular relevance. “For me, it is about challenging the note first. It is about subverting the note. It is about not accepting the note as pure. It’s about not accepting that the way I listen is the right way to listen. Once that happens, it is automatic that the word will also need to be subverted. I speak and write only because the note is not pure. It is not about searching for the perfect note, it is about realising the imperfection in the note. The perfect note doesn’t exist. It is a fraud. Realising the imperfections is what I seek as a musician. It’s in that grey space that gives authority neither to the note nor the word where music and poetry happen. It is in that space that a democracy truly flourishes.”

Read More:

“Yarukkaghilum Bhayamaa” – Whom should I fear, asks T M Krishna

Rhythm of Resistance: When T M Krishna Did Sing

Listen to T M Krishna Singing Perumal Murugan’s Verses of Exile

TM Krishna: “It is ironic that people who have built this large Hindu temple in a Christian country would take such a decision”