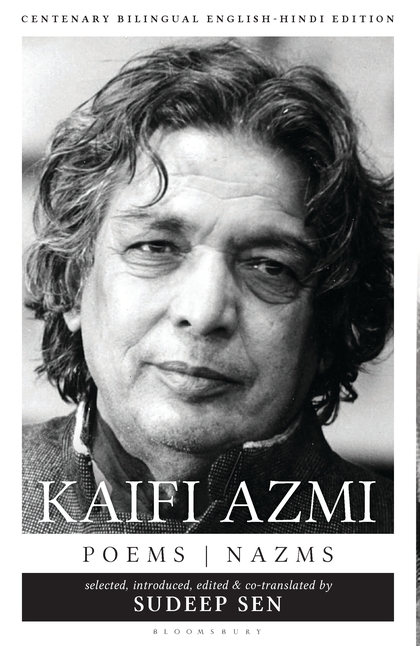

Kaifi Azmi: Poems | Nazms is an homage to Kaifi Azmi’s centenary birth year. The book, edited by Sudeep Sen, is a specially curated volume that contains 50 billingual — Hindi and English — poems. The contributors to the book are Husain Mir Ali, Baidar Bakht, Sumantra Ghosal, Pritish Nandy and Sudeep Sen. The book also contains archival photographs of the life and times of Kaifi Azmi.

The following are two poems by Azmi and their translations into English by Husain Mir Ali, along with a note from the translator.

Note on the translations

Kaifi Azmi begins Main Aur Meri Shaayeri, a reflective essay on his poetry, with the following words: ‘When was I born? I can’t remember. When will I die? I don’t know. All I can say with any certainty about myself is that I was born in an enslaved Hindustan, grew old in a free Hindustan, and will die in a socialist Hindustan. This isn’t the babbling of a mad man or the pipe dream of a fool. This belief is born from the deep connection that has always existed between my poetry and the great struggles for socialism being waged across the world and in my own country.’

Kaifi’s beliefs didn’t emerge from barren soil. He was politicised at an early age, having inherited his anti-colonial sensibilities from his grandfather, who had tried to thwart the British effort to grow indigo in his village by persuading his fellow farmers to roast the seeds before sowing them. A 10-year-old Kaifi once sought to organise an aborted black flag protest against a visiting British Collector. He also courted arrest, succeeding once only to be let off with a light caning by the police because of his age. Disappointed and eager to ensure that he would be detained the next time, he tried his hand at bomb-making with friends, but their childish effort literally fizzled out.

While the rest of his brothers received a modern education, Kaifi, the youngest, was sent to a madrasa in Lucknow for religious schooling. According to one commentator (who Kaifi himself approvingly quotes), ‘Kaifi was sent to a madrasa so that he could learn to perform the last rites of his parents, but instead, he came out having performed the last rites of religion itself.’ In an interesting twist of fate, it was at the madrasa that Kaifi came across Angaare, a scandalous collection of short stories written by four rebellious youth who would go on to create the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA), a trail-blazing literary group that spearheaded a hegemonic movement in Urdu literature for decades. Kaifi was to become one of the leading lights of the movement.

While in Lucknow, Kaifi was surrounded by and soaked up the energy of the anti-colonial movement. His rebellious spirit led him to organise a strike at the madrasa, during which he kept up the spirits of his comrades by writing and reciting fiery verse. His eagerness to join the struggle waging across the country meant that he never completed his formal education. His political journey took him to Kanpur as a young man where he became involved with the Mazdoor Sabha and was introduced to communist literature. He soon started working for the Communist Party of India and began living in its commune in Bombay, where he was joined by Shaukat Azmi, who he had met, and fallen in love with, in Hyderabad. Shaukat, who made the decision to eschew a life of relative comfort to marry and join Kaifi at the commune, would go on to become a comrade in the struggle and an important part of the Indian Peoples’ Theatre Association in her own right.

The PWA soon became a dominant force in Urdu literature and Kaifi made his mark in the movement as a quintessential progressive poet. The direct, powerful and unabashed poems in this selection mostly reflect Kaifi’s progressive politics. ‘Aadat’ is a dystopian view of a superficial world ruled by commerce, inhospitable to any thinking person. ‘Ibn-e- Maryam’ begins as a critique of the state of affairs in post-colonial India and ends with Kaifi exhorting Jesus to head to Vietnam instead, to save its people from the war being waged on them by Bible worshippers. ‘Bekaari’ is a strident critique of the exploitation of labour by capital, and builds up to a powerful climax, in which the discarded and marginalised worker seeks to rise up in revolt. ‘Telangana’ was written in support of the armed insurrection and peasant uprising of the 1940s against the ruling caste feudal landlords and the princely state. In ‘Taj Mahal’, Kaifi sees the iconic monument not as a beautiful mausoleum, but as a grotesque display of the world’s inequalities. ‘Saanp’ is both a lament on the subversion of science and progress by the power of money and capital, and a cautionary tale of how irrational sentiments embodied within organised religion suppressed true knowledge and promoted sectarianism. ‘Peer-e Tasma Pa’ is a sarcastic and despairing take on a similar theme. ‘Doosra Banwaas’ mourns the bloodshed during the resurgent communalism of the early 1990s. ‘Taj’ offers a harsh critique of monarchy and of the concentration of power. ‘Charaaghaan’ holds out hope for the future even as it bemoans the broken promises of Independence.

Kaifi ends his essay about his poetry on a less certain note than the one on which he begins it. He writes about how his early encounter with radical literature inaugurated the journey along a path that he faithfully and unwaveringly walked upon (despite my paralysis, he says). ‘One day’, Kaifi writes, ‘I will fall on this very path and my journey will end, at my destination, or at least, close to it.’

Kaifi and his comrades worked tirelessly, first for independence from colonial rule, and then later for an egalitarian and non-sectarian society, but his dream remains a work in progress. His poem ‘Inteshar’ ends with a demand: koi to sood chukaaye, koi to zimma le, us inquilaab ka jo aaj tak udhaar sa hai.

For Kaifi, the revolution is a debt that is still owed to him.

Unemployment

These arms, the strength of these arms

This chest, this neck, this power, this vitality

This passion of youth, this storm of courage

Without these, I have no worth

I have failed to do justice to both life and action

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

There is this earth, where treasures abound

The river, with jewels scattered on its bed

The jungles that are the envy of heaven-dwellers

But these prizes of nature are not for me

For I am destitute, deprived, and poor

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

Why don’t the mine owners ever summon me?

Why don’t the owners of the brightly-lit stores step forward?

Where, o where, are the owners of these factories?

Why don’t the owners of sparkling treasures purchase me?

For I am ready to sell my labour

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

Given the opportunity, I can make the sky bow down

Turn the stars into lamps that light the earth

Heat a fragment of clay such that it glows like the sun

Push the frontiers of progress even further

For I am smart, intelligent, and woke3

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

I am necessary to life and its continuation

I am necessary to the earth and the wind

I am necessary to the beginning and the end

I am necessary to civilization and progress

It’s ridiculous to claim that I am the obstacle

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

Those who worship wealth are poor judges of worth

Looters and marauders are unfamiliar with love and gentleness

I am left with this thirsty existence, this hungry youth

I am cold lightning, I am stagnant water

I am the stalled sword, the diverted stream

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

It’s my bones that were used to make these palaces

It’s my blood that has produced the freshness of spring

This glittering wealth is built on my poverty

These shining coins require my dispossession

I am the rust on these sparkling treasures

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

How long can this I suffer this oppressive existence

The ways of the world are beginning to change

My blood is at a boil, there’s sweat on my brow

My pulse pounds, my chest is on fire

Roar o revolution, for I am ready

It upsets me greatly that I am unemployed

बेकारी

यह बाज़ू, यह बाज़ू की मेरे सलाबत

यह सीना, यह गर्दन, यह कुव्वत, यह सेहत

यह जोश-ए-जवानी, यह तूफ़ान-ए-जुरअत

ब-ईं-वस्फ़ कुछ भी नहीं मेरी कीमत

हयात-ओ-अमल का गुनहगार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

यह गेती है जिसमें दफ़ीने मकीं हैं

वह दरिया है जिसमें गुहर तहन तहनशीं हैं

वह जंगल हैं को रश्क-ए-ख़ुल्द-ए-बरीं हैं

ये फ़ितरत के इन्आम मेरे नहीं हैं

तहिदस्त-ओ-महरूम-ओ-नादार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

पुकारें ज़मीनों के कानों के मालिक

बढ़ें जगमगाती दुकानों के मालिक

कहाँ मैं कहाँ कारखानों के मालिक

खरीदें छलकते ख़ज़ानों के मालिक

कि मेहनत-फरोशी को तैयार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

जो मौक़ा मिले सर फ़लक का झुखा दूँ

ज़मीं पर सितारों कि शमाएँ जला दूँ

ख़ज़फ़ को दमक दे के सूरज बना दूँ

तरक़्क़ी को कुछ और आगे बढ़ा दूँ

कि चालक-ओ-हुशियार-ओ-बेदार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

ज़रुरत है मेरी हयात-ओ-बक़ा को

ज़रुरत है मेरी ज़मीं को, फ़िजा को

जरूरत है हर इब्तिदा इन्तिहा को

ज़रुरत है तहज़ीब को इर्तिक़ा को

ग़लत है कि इक हर्फ़े-ए-तकरार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकरार हूँ मैं

कहाँ ज़रपरस्ती कहाँ क़द्रदानी

कहाँ लूट ग़ारत कहाँ मेहरबानी

यह बे-आब हस्ती, यह भूखी जवानी

यह यख़बस्ता बिजली, यह इस्तादा पानी

रुकी तेग़ हूँ मैं, मुड़ी धार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

मिरी हड्डियों से बने ये ऐवॉं

मिरे ख़ून से है यह सैल-ए-बहारॉंं

मिरी मुफ़लिसी से ख़ज़ाने हैं तबॉं

मिरी-बे-ज़री से हैं सिक्के दरख़्शाँ

इस आईनः-ए-ज़र का ज़ंजार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

कहाँ तक यह बिलजब्र मर-मरके जीना

बदलने लगा है अमल का क़रीना

लहू में है खौलना जबीं पर पसीना

धड़कती हैं निब्जे़ं सुलगता है सीना

गरज ऐ बग़ावत, कि तैयार हूँ मैं

बड़ा दुख है मुजको कि बेकार हूँ मैं

The Second Exile

When Ram returned home from his exile

He began to miss the jungle as soon as he arrived into the city

When he saw the dance of madness playing out in his courtyard

on 6 December, Shri Ram must have wondered:

How did so many mad people enter my home?

Where Ram’s footprints had once sparkled

Where love’s galaxy once stretched out its arms

That path had taken a turn towards hate

No one would have been the wiser about their religion or

their caste

They would have gone unrecognised had it not been for the

light from the burning home

They, who had come to my home in order to burn it

I know your daggers were vegetarian, my friend

And that you had thrown your stones only towards Babar

It’s the fault of my own head that it got bloodied

Ram hadn’t even washed his feet in the Sarju river yet

When he noticed the deep stains of blood

Getting up from the river’s edge without washing his feet

Ram took leave of his home saying:

The atmosphere of my capital doesn’t agree with me

This 6 December, I am exiled once again

दूसरा बनबास

राम बनबास से जब लौट के घर में आए

याद जंगल बहुत आया, जो नगर में आए

रक़्स-ए-दीवानगी आँगन में जो देखा होगा

छह दिसंबर को स्रीराम ने सोचा होगा

इतने दीवाने कहाँ से मिरे घर मे आए.

जगमगाते थे जहाँ राम के क़दमों के निशाँ

प्यार की कहकशाँ लेती थी अँगड़ाई जहाँ

मोड़ नफ़रत के उसी राहगुज़र में आए

धरम क्या उनका था, क्या जात थी, यह जानता कौन

घर न जलता तो उन्हें रात में पहचानता कौन

घर जलाने को मिरा, लोग जो घर में आए

शाकाहारी थे मेरे दोस्त तुम्हारे ख़ंजर

तुमने बाबर की तरफ़ फेंके थे सारे पत्थर

है मेरे सर की ख़ता, ज़ख़्म जो सर में आए

पाँव सरजू में अभी राम ने धोये भी न थे

कि नज़र आए वहाँ ख़ून के गहरे धब्बे

पाँव धोए बिना सरजू के किनारे से उठे

राम यह कहते हुए अपने द्वारे से उठे

राजधानी की फ़िज़ा आई नहीं रास मुझे

छह दिसंबर को मिला दूसरा बनबास मुझे