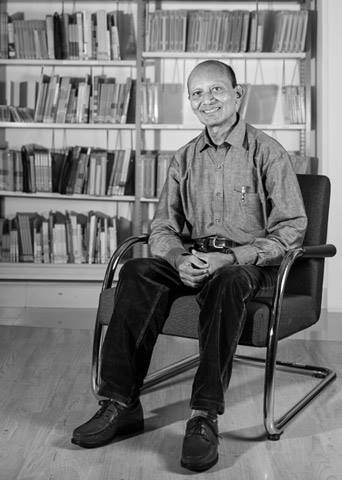

Neerav Patel, a pioneering Gujarati Dalit poet, passed away on 15 May, 2019. A bi-lingual poet, he wrote in English and Gujarati. During the last few days of his life he fought the cancer with the same indomitable spirit that imbues his poetry. When he could not speak he kept a notebook and pen, communicating with his many visitors – friends and well-wishers – through notes. From mid-December 2018, when the cancer did not let him sleep, he wrote a poem almost everyday and posted it on his social media page. A total of 68 poems. Each of these poems is a testament to his spirit of resistance. Strident and politically charged, these poems address issues from “sabka saath, sabka vikaas”, to untouchability, to the demand for reservations by uppercastes and the purpose of poetry.

Patel’s was a significant voice not just in Gujarati poetry but also in Indian poetry. His words captured the pain and experience of the material life of Dalit communities. One of the most widely read and translated of Gujarati poets, his poetry has been translated into several Indian languages as well as English and German. Though Dalit poetry remains marginalised in the Gujarati literary sphere, Neerav Patel was widely published and celebrated. In the past few years his poetry appeared in most of the major Gujarati magazines, literary and otherwise – Parab, Shabda Shrushti, Nireekshak, Naya Marg and Navneet Samarpan.

Deeply committed to the cause of Dalit literature, Patel was closely associated with the Dalit Panthers of Gujarat (inspired by the Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra, especially the poet Raja Dhale). He was one of the founding editors, along with Dalpat Chauhan, Yogesh Dave and Pravin Gadhvi, of the first Dalit literary magazine, Aakrosh (1978), published by the Dalit Panthers. His poem on the Jetalpur burning, when a young Dalit man named Shakrabhai Premabhai was burnt alive on the allegation of theft in the village of Jetalpur on 26 December, 1980, is a searing critique of caste hierarchies and a bold political statement. Patel calls it a ‘report poem’. Indeed, for Patel the subject matter of poetry could not be separated from the stark social and political realities of everyday life for Dalit communities.

As Deeptha Achar says, he was one of the first Dalit poets to make a conscious choice of writing in English. His first two collections of poetry, Burning From Both The Ends and What Did I Do To Be So Black And Blue, were written in English and published by the Dalit Panthers of Gujarat in the 1980s. Very few Dalit writers even today choose to write in English, and when young Dalit poet Chandramohan began writing Dalit poetry in English, he found he had no mentors. He says, “I used to feel so orphaned that most of them wrote in their native tongues and didn’t possess enough command over English to read and critique poetry written in English and have a fruitful conversation on the nuances of a cultural text conceived in English. He was one of the few Dalit writers well-versed in English; this helped me in sustaining a conversation with him.” Always unflinching in his commitment to the cause of Dalit Literature, Patel advised Chandramohan to stay away from the media and limelight, read voraciously and hone his craft. This is a dictum he followed himself. He read widely and deeply. In his writing and conversation he would refer just as easily to Sarte as to Ambedkar, to Sisyphus as to Shambhuka, to Paul Robeson as to Baburao Bagul.

Patel’s commitment to Dalit literature is evident in his work with various Dalit literary organisations, publishing books and magazines, conducting workshops and other programmes. As an editor he was prolific. He edited several literary magazines in succession, even editing of the first anthologies of Gujarati Dalit poetry published by the Sahitya Akademi. Not only was he devoted to Dalit poetry, as an editor he sought to contextualise it, including interviews, sociological and other scholarly essays.

A bank officer for most of his working life, Patel was never at ease in the upper caste, middle class staidness it represented. In a preface to his collected poems, he says that the word poetry is ‘misleading’ (chetraamno). Misleading because for him poetry is not about the familiar, romantic tropes of traditional Gujarati poetry. It cannot be. His poetry does not please, or entertain. As he says, writing poetry gives him pain and he wishes that the reader not be just a reader but a ‘hamdard’ (someone who empathises). Neerav Patel has opened our world and made us all ‘hamdard’.

Song of our shirt

We are such a fashionable jati.

Our ancestors

used to wear three-sleeved shirts.

Their ancestors

used to wrap a shroud around themselves

as a shirt.

And their ancestors

used to wander in their own bare skin.

I am no less fashionable!

See me in this sleeveless, buttonless, collarless shirt

from a seth on C G Road?

As I sweep the foot path, I wear it with style.

Strutting around bare chested like Salman Khan,

showing off my muscles like Sanjay Dutt.

Their young women are dying to see the label.

How will they be able to see

without touching this

untouchable neck

that it is an odd-sized

Peter England!

Yes, we are an ultra-fashionable kom.

The inspiration for Neerav Patel’s poem

The inspiration for Neerav Patel’s poem

To each, their own Gandhi

Today is 30 January,

an unholy day in independent India.

All Indians remembered Gandhi

in their own way.

In a country turning to hell

everyone remembered him

specially.

Hindu Mahasabha also memorialised him:

In Aligarh, they celebrated

Gandhi vadh divas

and Godse shaurya divas.

With a toy pistol, three shots were fired

into Gandhiji’s statue.

The packet of dye secreted in the statue’s chest

burst, mock blood flowing.

Then, like Ravanadahana, the executives of the Mahasabha

slayed the state of the Mahatma

to bold slogans of ‘Nathuram Godse Zindabad’.

Then everyone offered garlands

to the image of Godse, bowing before it.

Sweets were distributed.

Gandhiji brought us independence:

Now we are all independent,

able to do as we like.

Perform a Gandhi vadh,

pray to Godse.

The Constitution, our rulers and our courts

give complete freedom

todesh bhaktas to express their emotions.

You are independent.

You are free to do anything,

kill, lynch, stage encounters –

you can celebrate your freedom any way you like.

30 January 2019

Both poems translated from the Gujarati by Gopika Jadeja.

Gopika Jadeja is a poet and translator from India who writes in both English and Gujarati. She publishes and edits the print journal and a series of pamphlets for a performance-publishing project called Five Issues. Her work has been published in Asymptote, The Wolf, Indian Literature, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Vahi, Sahcharya, etc. Gopika is currently working on English translations of poetry from Gujarat.