Samina Mishra is a writer, documentary filmmaker, editor and curator. She is the author of several books for children including My Sweet Home: Childhood Stories from a Corner of the City (2017), 101 Indian Children’s Books We Love (2012), Madhav and the Magic Balloon (2012), and My Friends in the City (2007). Her documentary film The House on Gulmohar Avenue traces her personal journey to understand what it means to be a Muslim in India. In this interview, we speak to her about her work, the complex “insider-outsider” positions that she inhabits, and what makes children’s books special.

Kanika Katyal (KK): I am intrigued by your project for the India Foundation for the Arts, on how the State, as embodied by the Children’s Film Society of India (CFSI), imagined and represented the child, from its inception in 1955 to the early 1980s. Could you please tell us more about the project in terms of the repository of images and narratives that you used, the primary focus of your inquiry, how the films were produced, disseminated, received, etc.?

Your project proposal states, “The researchers will study the CFSI archive, examining its institutional engagement with the figure of both the real and metaphorical child.” What do you mean by the “real and metaphorical child”?

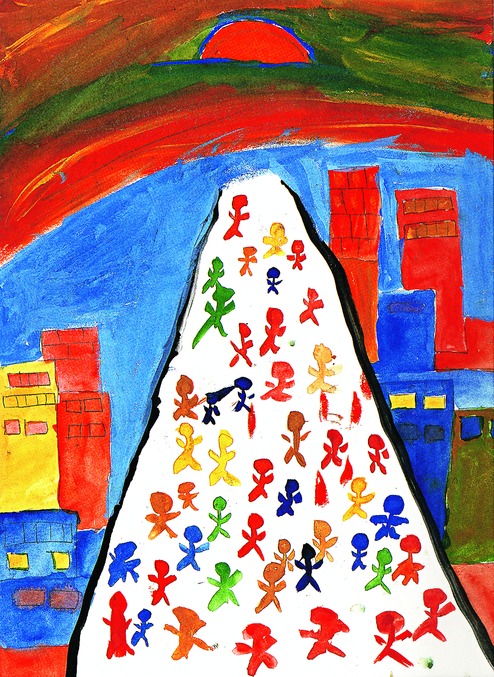

Samina Mishra (SM): The CFSI archive is a huge body of work created specifically with the child in mind – and at a critical point in our history. It was set up in 1955 in the immediate phase of nation-building, like many other state-supported organisations dealing with culture – for example, the Films Division (1948), ICCR (1950), National Gallery of Modern Art (1954) – that were born out of or developed under the Nehruvian vision. CFSI’s objective was to undertake and organise the “production, distribution and exhibition of feature films and shorts for children, provide them healthy and wholesome entertainment, aim to enhance their knowledge, develop their character, broaden their perspective and help shape them into useful citizens of modern India.” The films in the early decades take up issues of class, caste, education. Many of the films are about the encounter between children of different class backgrounds (Jawab Ayega), many are about the middle-class child having an adventure in a rural/natural setting (Kala Parbat), there are films set in remote areas (Jaldeep), a film set in the context of the 1962 war focussing on the contribution of children to the war effort (Boond Boond Mein Sagar). These indicate how the films sought to construct the idea of the Indian nation, and the child-citizen as a symbol of hope. So, the metaphorical child is the child-citizen representing the ideal citizen, the one that a nation, perceiving itself as benevolent, sought to fashion in the nation-building project of the post-independence years – the idea of unity in diversity embodied in children, the future of the nation. This is also why dissemination through mobile vans and projectors was an important activity of CFSI in the early years.

But the reality of childhood is complex and diverse and the CFSI films from this period reflect how the benevolent approach came from the standpoint of the middle-class child. And so, while the films argue for a progressive, more equitable world in which children are given space and agency, at the same time, they do not question the larger structural framework. So, the focus remains on the change of heart or enlightenment that can bridge the divide and enable harmony.

This complex and complicated space has much to teach practitioners like me who create art and media for children today. The divisions in society are much sharper now and so we really need to think about how we talk to children about these ideas – how do we find an approach that does not reproduce these divisions despite good intentions and how we tell stories that children themselves want to read/see rather than the adults forcing those upon them.

The project was like dipping a toe into the archive and there were many challenges. So we see it as a beginning, something that needs more work. The research led to a presentation of the work done by Nandini and me, and we had hoped to continue working more on the idea but unfortunately, we have not been able to so far.

KK: When curating a list of films or books for children, what are the things you look for?

SM: The artistic merit of the film/book itself has to be foremost – does it tell an engaging story or present an engaging experience. And this is about both content and form. A good story but also one that is told well. Also, what is very important for me is that the film/book respects children and does not patronize them. This requires an understanding of what it can mean to be a child, not an approximation of what we imagine children to be but an understanding that comes from our own lived experiences.

KK: Do you feel that art, literature or film for children’s amusement is an underrepresented field in India?

SM: Definitely! Things have/are improving in some ways – children’s literature, for example. But films are more expensive to produce and disseminate and so while there are efforts, there is much more that is needed.

Image Courtesy: PSBT

Image Courtesy: PSBT

KK: Your film The House on Gulmohar Avenue is about your personal journey to understand your roots, but in the form of a documentary. What was your idea behind depicting the personal and autobiographical in documentary format?

SM: I have come to creative practice through the documentary. I am very interested in the every day and how it is a window to larger ideas, and how politics is enacted through the everyday. So, it was an instinctive choice. I wanted to tell a story about the complicated-ness of identity in the context of what was going on in India. So, I knew I had to include my family’s story – because I have a hybrid-sounding name and have grown up answering the question, “How come you are Muslim?” My great-grandfather’s house in Okhla, built when Jamia Millia Islamia was founded, became a starting point. The house used to be rented out to the Jamia as the VC’s residence but when the lease ended sometime in the early 1990s, my grandmother decided not to rent it out anymore. She was going to fix it and her children were all going to get a share in it. It was lying empty and I used it for a student project. And somewhere along the way, I became connected to it and to a sense of legacy. I say this with the awareness that this has feudal roots – but that is the honest answer. What I hope is that while the link may have emerged from a history that is part feudal, my work has been critically aware of that and that it includes more than just a nostalgic, privileged perspective. I saw the changes in Okhla as mirroring some of the larger changes taking place in the country and I wanted the film to be about the diversity of those experiences. So, the film became about my personal journey along with the intersecting stories of others who inhabit the same space.

KK: Your books, My Sweet Home and My Friends in the City, talk about not just the city through ideas of home for humans but also describe animals as our friends whom we share the city with. It also shows the various parks or market places that are not prescribed spaces but ones we interact with in our day-to-day lives. Did you view it as a foray into the field of “urban studies”?

SM: Gosh, “urban studies” makes it seem like such a considered decision… the truth is sometimes ideas just come into your head, sometimes they grow organically from work you’re doing. Of course, they emerge from your experiences, what you have absorbed about looking at the world, what you have read and watched, how you engage with other people… As an urban citizen, my everyday encompasses spaces that may find marginal representation and my way of looking at the world is one that seeks more equity. So, those things will influence my storytelling. But I don’t think it’s for me to say that this is about urban studies, that’s for others who read/analyse the books. For me, they are stories I wanted to tell, ideas I wanted to share with children that I believe they should think about, spaces and people that I think they should not overlook.

KK: In The House on Gulmohar Avenue, you end the film with a beautiful line. While talking about the various entanglements of history, you ask, “Is there a history that is simple?” – do you think children’s literature offers a possibility to find answers to that question?

SM: I think I am a romantic and I see children embodying possibility. This is both a truism and a cliché. But one that we have to believe in if we want to believe that the world can be a better place. I also believe very strongly that art shows us the possibilities for a better, more equitable, a kinder world – in both a public as well as a personal way. And it does that by allowing for a plural, layered understanding of the world, for its messiness and its order, its many voices… So of course, the answer to that rhetorical question is – No. And art and literature can show us how it is “no”, how we have complicated histories and how it is possible to live with those complicated histories without losing our humanity. So that is why I engage with art for children, and also why I like to teach.

KK: “A life, a home, and identity”: are phrases from your own film, but I feel they are the meditations informing all your work. Do you agree? Would you like to contemplate on that?

SM: Yes, I think you are right. It did not come as a conscious decision but looking back at the work I have done, I feel it is a search for an understanding about who we are and where and how we belong. Isn’t this everyone’s quest, in different ways? Isn’t this the purpose of art and of education – to make sense of who we are, and of the world we live in as well as the world we choose to build? Our struggles as individuals – both in the personal and in the public space – are actually about that. About our sense of ourselves, and how that fits in with others we choose to live with. The road to a sense of self is a long one, though, and people like me who work in the arts are in many ways lucky because our work forces us to interrogate ourselves. You cannot interrogate the world without interrogating yourself. And it is in that process that you find an understanding of “life, home and identity”.

Image Courtesy: The Telegraph

Image Courtesy: The Telegraph

KK: Your latest book, My Sweet Home and My Friends in the City, is based in Okhla, a region in South Delhi called “mini-Pakistan”. It seems a shuddering thought to bear from the outside-looking-in. What are the (real) limitations as well (creative) freedoms that inform the process of documenting an intense subject like that? How do you balance them in your work?

SM: My Sweet Home is based in Okhla and is actually not my latest book. I have one more out after that – Shabana and the Baby Goat, a picture book for Tulika. My Friends in the City is an old book. But yes, my work does include perspectives that can be seen as from the outside-looking-in. So of course, this is an issue – how do you write about people or spaces that are very different from you or your life? I think I have been helped by my documentary practice in this regard. Documentary film is so often about people not like yourself that you have to be very critically aware of how you are representing them. I think I try to be honest about my position – while I am not an “insider”, I also think the binary of “insider-outsider” is a bit narrow because there are many on the “inside” who may feel they are different. I also engage with the every day as a way of creating a more layered representation. Like I said earlier, the everyday interests me in how it reflects larger ideas. So, My Sweet Home may have been prompted by the extraordinary – the Batla House encounter – but that is only one part of the book. The book is about the everyday experiences of childhood – sometimes commonplace, sometimes special. And that allows for a more complex experience of the space and the children in the book. Although people may still come to the book from that one-dimensional idea – oh it’s the about kids and the Batla House encounter or it’s about Muslim kids – or even reject it coming from that position. But hopefully, if given a chance, the book will be about much more than that for the reader because it is about many kinds of experiences.

With My Sweet Home, the sense of freedom and limitations came more from the way in which the book grew. It was freeing because it was not being done for delivery or deadline, there was no fixed idea or format, we could experiment with it. Sherna and I worked on it as a documentary film edit. But the limitation is that it cannot be slotted easily and so it was not easy to find a publisher for it who would accept our vision of the book. And now that it’s out in the market, that is still a challenge – where to slot the book. I have shared the book with different groups of children at festivals and other places, and I have found the children engaging with the ideas. I have also shared it with teacher educators and they found it an extremely useful resource. So, it cuts across fixed boxes… I think the whole “finding a slot” thing is perhaps more of a marketing-driven challenge. But that is also a reality of our times where the onus of pushing at boundaries lies more and more on individuals unsupported by larger structures and so, as a creative practitioner, you have to accept that you have to do more and that certain kinds of books will be more successful than others.

Read More:

“Writing has become a response to the political horrors of the present”

“The Work of the Poet is the Work of the Historian”: Najwan Darwish

Aamer Hussein: Weaving Stories from Memories, Myths and Fables