In the equality jurisprudence, there are two schools of thought that emerge while addressing the issue of reservations. There is one that believes that providing a special pedestal, or a forward push to certain communities in the form of reservation in public employment, exacerbates the difference, thereby enhancing inequality and discrimination.

The other school of thought maintains that reservation as a form of affirmative action is a way of achieving an equal footing; by providing an extra push, the historical wrong to certain communities is being compensated. This is also termed as compensatory discrimination.

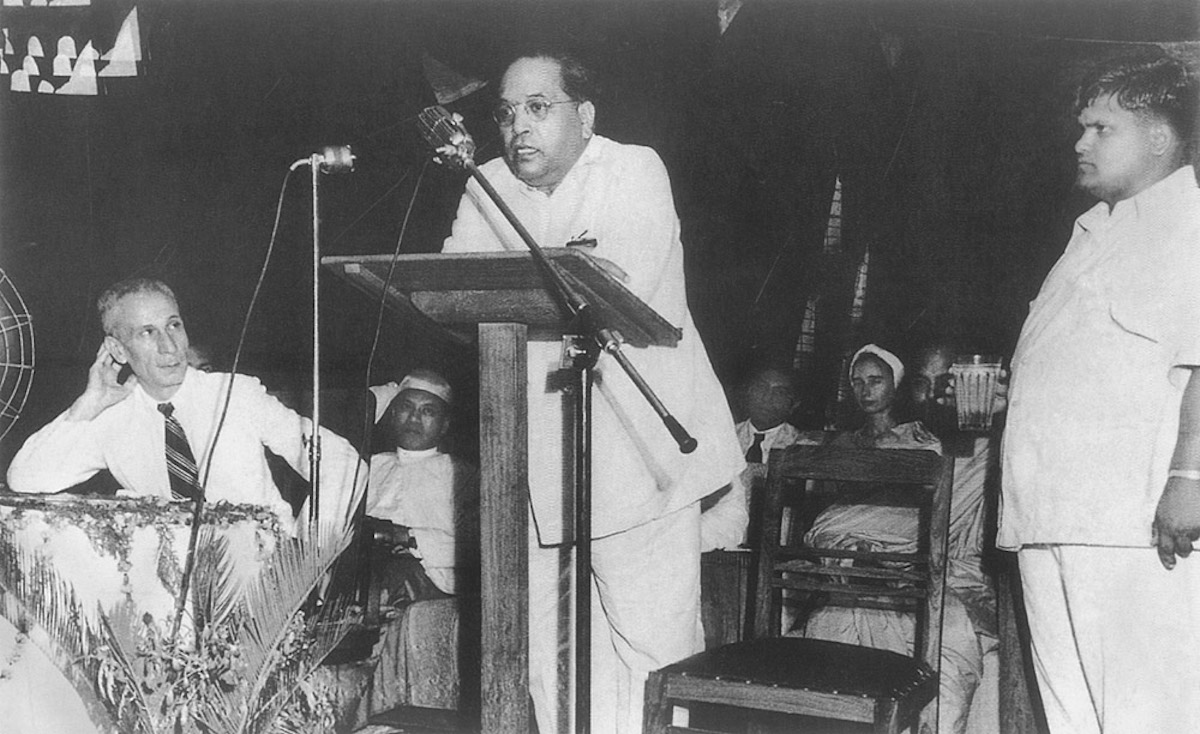

During the Constituent Assembly Debates on Article 16, the then Article 10 of the Draft Constitution, Dr B R Ambedkar explained the dichotomy in two schools of thought of equality jurisprudence. However, he maintained that theoretically guaranteeing everyone “equality of opportunity” may not be possible without reservations for those who had faced a historical disadvantage. To quote him from the debate dated November 30, 1948:

“At the same time, as I said, we had to reconcile this formula with the demand made by certain communities that the administration which has now – for historical reasons – been controlled by one community or a few communities, that situation should disappear and that the others also must have an opportunity of getting into the public services. Supposing, for instance, we were to concede in full the demand of those communities who have not been so far employed in the public services to the fullest extent, what would really happen is, we shall be completely destroying the first proposition upon which we are all agreed, namely, that there shall be an equality of opportunity. Let me give an illustration. Supposing, for instance, reservations were made for a community or a collection of communities, the total of which came to something like 70 per cent. of the total posts under the State and only 30 per cent. are retained as the unreserved. Could anybody say that the reservation of 30 per cent as open to general competition would be satisfactory from the point of view of giving effect to the first principle, namely, that there shall be equality of opportunity? It cannot be in my judgment. Therefore the seats to be reserved, if the reservation is to be consistent with sub-clause (1) of Article 10, must be confined to a minority of seats. It is then only that the first principle could find its place in the Constitution and effective in operation.”

In the Constituent Assembly, it was pointed out by one member that Article 16(4) would become a paradise for lawyers. Interestingly, it is not far from the truth

Reservations in public employment has been a contentious issue under the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution that has been amended, as well as given varying interpretations by the Supreme Court over the last seven decades. From the multiple issues that come under the umbrella of reservations, in this article, I will trace in brief the constitutional history of issue of reservations in promotions in public employment.

Article 16: Equality of opportunity in matters of public employment

- There shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters of public employment or appointment to any office under the State.

…

(4) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.

In Indra Sawhney v. Union of India[1] the Supreme Court held that reservation in promotion was not desirable and Article 16(4) did not permit reservations in matter of promotions. It held that:

“741…Art. 16(4) is not an exception to the Art. 16 (1) but, that it is only an emphatic way of stating the principle inherent in the main provision itself. …In our respectful opinion, the view taken by the majority in Thomas (supra) is the correct one. We too believe that Art. 16(1) does permit reasonable classification for ensuring attainment of the equality of opportunity assured by it.”

Reservations in public employment has been a contentious issue under the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution that has been amended, as well as given varying interpretations by the Supreme Court over the last seven decades.

- …“The question then arises whether clause (4) of Article 16 is exhaustive of the topic of reservations in favour of backward classes. Before we answer this question it is well to examine the meaning and content of the expression ‘reservation’. Its meaning has to be ascertained having regard to the context in which it occurs. The relevant words are ‘any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts’. The question is whether the said words contemplate only one form of provision namely reservation simpliciter, or do they take in other forms of special provisions like preferences, concessions and exemptions. In our opinion, reservation is the highest form of special provision, while preference, concession and exemption are lesser forms. The constitutional scheme and context of Article 16(4) induces us to take the view that larger concept of reservations takes within its sweep all supplemental and ancillary provisions as also lesser types of special provisions like exemptions, concessions and relaxations, consistent no doubt with the requirement of maintenance of efficiency of administration — the admonition of Article 335. …”

- 858. … (7) Article 16(4) does not permit provision for reservations in the matter of promotion. This rule shall, however, have only prospective operation and shall not affect the promotions already made, whether made on regular basis or on any other basis. We direct that our decision on this question shall operate only prospectively and shall not affect promotions already made, whether on temporary, officiating or regular/permanent basis. It is further directed that wherever reservations are already provided in the matter of promotion — be it Central Services or State Services, or for that matter services under any Corporation, authority or body falling under the definition of ‘State’ in Article 12 — such reservations may continue in operation for a period of five years from this day. Within this period, it would be open to the appropriate authorities to revise, modify or re-issue the relevant rules to ensure the achievement of the objective of Article 16(4). If any authority thinks that for ensuring adequate representation of ‘backward class of citizens’ in any service, class or category, it is necessary to provide for direct recruitment therein, it shall be open to it to do so. (Ahmadi, J expresses no opinion on this question upholding the preliminary objection of Union of India). It would not be impermissible for the State to extend concessions and relaxations to members of reserved categories in the matter of promotion without compromising the efficiency of the administration.”

The 77th Constitution Amendment

The Parliament of India enacted the Constitution (Seventy-Seventh Amendment) Act, 1995, providing for reservation in promotion and overruled Indra Sawhney on this point. Article 16(4A) was inserted in the Constitution, and it came into effect from 17-06-1995.

The 77th Constitutional Amendment inserted the provision of Article 16(4A), making reservation in promotion a fundamental right. However, this provision limits its application to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Contrary to this, Article 16(4) applies to reservation in appointments and posts for “backward classes”, without making any special distinction for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

85th Constitution Amendment

By way of 85th Constitutional Amendment, in 2001, the words “consequential seniority” were included after reservations in promotions in Article 16(4A), and it was said to be in effect from June 17, 1995, i.e. the same date on which “reservation in promotion” was instituted in the Constitution by way of 77th Constitution Amendment.

“Consequential seniority” means that seniority in public services would be given as an automatic consequence of promotions to SC/ST persons given by way of reservations.

The Constitutional validity of 77th and 85th Constitutional Amendment were challenged in the case of M. Nagaraj v. UOI[2]. The judgment of the Supreme Court vide a five-judge bench upheld the validity of Article 16(4A). However it inserted a few conditions, upon satisfaction of which, States had the power to provide for reservations in promotions for SC/ST. These “compelling factors” as held by the Supreme Court were:

- quantifiable data regarding backwardness

- Inadequacy of representation in public services

- No impact on the overall efficiency of administration by way of such reservation

It held:

“The State is not bound to make reservation for SCs/STs in matters of promotions. However, if they wish to exercise their discretion and make such provision, the State has to collect quantifiable data showing backwardness of the class and inadequacy of representation of that class in public employment in addition to compliance with Article 335. It is made clear that even if the State has compelling reasons, as stated above, the State will have to see that its reservation provision does not lead to excessiveness so as to breach the ceiling limit of 50% or obliterate the creamy layer or extend the reservation indefinitely.”

The 77th Constitutional Amendment inserted the provision of Article 16(4A), making reservation in promotion a fundamental right. However, this provision limits its application to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Contrary to this, Article 16(4) applies to reservation in appointments and posts for “backward classes”, without making any special distinction for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The question of producing quantifiable data to prove “backwardness” for granting reservation in promotion to SC/ST was recently decided by the Supreme Court in Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta[3]. The Supreme Court vide a five-judge bench held that there was no need to provide data for assessing backwardness of the SC/ST community as they are presumed to be backward. However, while reading down one of the compelling factors of M Nagaraj, the Supreme Court did uphold that a State wanting to grant reservation in promotions as per Article 16(4A) would have to conduct a study to show inadequacy of representation of SC/STs in their public service, while showing that overall efficiency of the State administration was maintained.

In the Constituent Assembly, it was pointed out by one member that Article 16(4) would become a paradise for lawyers. Interestingly, it is not far from the truth. Currently, there are litigations ongoing in the Supreme Court on statutes enacted by different states across the country that provide for reservation in promotion and consequential seniority. Their final adjudication after the application of the judgement in Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta[4] is still pending.

[1] 1992 Supp. (3) SCC 217

[2] 2006 (8) SCC 212

[3] 2018 SCC Online SC 1641

[4]2018 SCC Online SC 1641