A professor of political science, Prabhakar, comes upon a corpse at a crossroads, naked but for the skullcap on his head. Days later, he listens to a friend’s stark retelling of a gang rape in a village, as chilling as only the account of a victim can be. And in a macabre sequence, he finds his favourite dhaba no longer serves gular kebabs and rumali roti, while Bonjour, the fine dining restaurant run by a gay couple, has been vandalised by goons. Casting a long shadow over it all is Mirajkar, the ‘Master Mind’, brilliant policy maker and political theorist, who is determined to rid the country of all elements ‘alien’ to its culture.

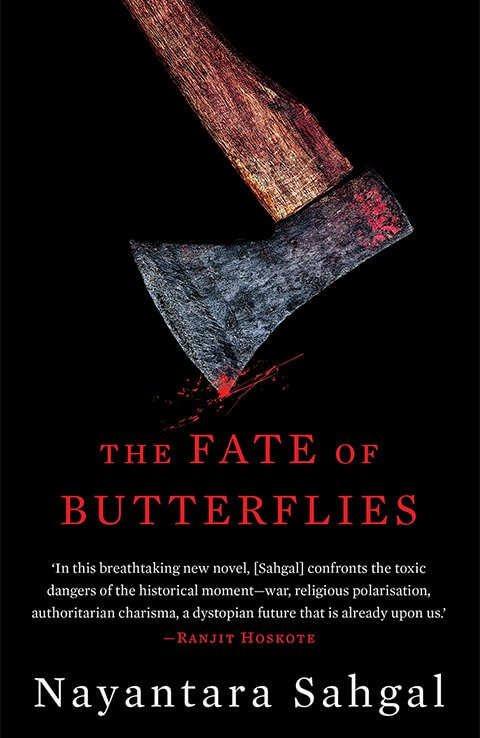

In The Fate of Butterflies, Nayantara Sahgal reveals, in masterly detail, the unraveling of the idea of India. But she also offers hope — in people speaking up for each other; reclaiming citizenship with compassion and friendship; and seeking the meaning of life in love. The following is an excerpt from the book.

A suggestion came from Katerina at dinner that night at Rahman’s. ‘Rafeeq’s home must be in one of the areas they’re driving people out of and setting fire to, like the village I was asigned and other villages around there, or digging up grounds like the graveyeard. They call it taking back the land occupied by invaders.’

Rahman had been unlike himself, unnaturally subdued since the excavation of the graveyard. It was Salma who asked where the villagers driven out of their homes had gone. Katerina didn’t know, but one of her colleagues and co-writer on their book project had said that in her country the policy of wiping out a religion had herded whole families into camps, made displaced people of them while it was decided what to do next. These were very primitive makeshift shelters with no proper sanitation or water supply or electricity. People had to rig up their own electric wiring and scrounge around for wood to cook on.

‘How did she know? Did she see one of these camps?’ asked Salma.

‘She lived in one of them. She was one of the herd driven into them. She said guards used to come at night and separate the women from the men…’

Katerina sensed violent recoil like a live presence in the room and gave it a minute before continuing, ‘We will have to find out where those villagers are, if they’ve been put in a camp, and go there.’ Another second of silence told her no one else’s mind had jumped ahead to that course of action. ‘Of course, Rafeeq may not be there but that’s where he’s most likely to be. We’ll have to go and see.’

She must not go with them, they protested. Rahman, with his habitual tenderness for mankind and more especially for womankind, said it would be exhausting and emotionally too much of a strain after all she had been through. As if she hadn’t heard, Katerina told them she would make enquiries tomorrow morning and go with them. She had never met Rafeeq and wouldn’t recognize him, but Rahman had said he had a wife and two children so she would ask among the women. It could be useful. It had to be agreed she would go with them tomorrow afternoon after classes, giving her the morning to find out where the camp, if there was one, was located.

At the sprawl of tents, hutments and flimsier shelters concocted out of tin and tarpaulin, Katerina suggested they divide up for a thorough search for Rafeeq, not just look around for him but keep asking if anyone knew him or had seen him. Prabhakar took the direction given. He had not imagined quite this. There was a finality about this mass removal, clealy no hope of escape from it. There would be no going back to where they had come from, or forward to elsewhere, for those expelled from their village lands and their livelihoods who now had nothing to do and nowhere to go. This squalor had no shape or form and no connection with anything he thought of as human habitation. Yet human voices were telling him they knew no one called Rafeeq; the sun was beating down on barefoot children chasing each other through the mud of narrow alleys between shelters or playing marbles in the dirt; an infant howling behind a makeshift curtain of cloth thrown over a rope, was soothed, lulled, and must have slept; cooking fires were being fanned, hot sparks flying into the hot air. He walked on through the sound of men’s voices, the chatter of quarelling children, a woman pounding clothes in the scanty water from a tap—signs of humanity obstinately alive in the nowhere of displacement. In a patch of shade two old men squatted, staring into space. They, at least, had recognized the permanence of their plight. Coming to a tent at the end of his area he called out and lifted a tent flap by its corner, hoping to get some information from those within, and let it drop, paralysed by his transgression. A woman labouring strenuously to give birth lay on straw matting on the ground, her legs wide open, her body writhing, her groans unmindful of all but the merciless rhythm of labour. The woman keeping vigil between her legs had paid him no attention. He walked back, his stomach convulsed by the sight and sounds of birthing, the ultimate act in defiance of extermination.

On their way home, an hour’s drive, Rahman at the wheel, there was little to be said about the failure of their mission. Their separate silences bound them closer than talk. Prabhakar, sitting beside Rahman, felt sickened at the thought that Rafeeq might have been beaten to death and his body left rotting on some roadside. Where could his family be hiding and how long could they hide? He understood why Rahman had nothing to say. In deep mourning for the man he had known, for the faith they had shared, and for their brotherhood with all others under the Indian sun, what is there to say?