At 6:26 am on May 1, 1960, Francis Gary Powers guided a super-secret U-2 plane of the CIA, also called the “giant black crow”, on the tarmac of a clandestine American airbase in Peshawar, Pakistan. Perspiring inside the cockpit, Powers was soon in the skies, headed northeast towards the Soviet Union. His mission was to film the Soviets’ ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) bases with an on-board Hycon B camera. He had climbed to 70,000 feet. But just as he was over Sverdlovsk in eastern Soviet Russia, Powers felt a “WHUMP”. The U-2 had been hit by a Soviet ground-to-air missile. Soon the wings of the spy plane tore off and the damaged aircraft spun earthward. Powers ejected and at 15,000 feet his parachute jerked open. Below, a small detachment of the Red Army waited for him.

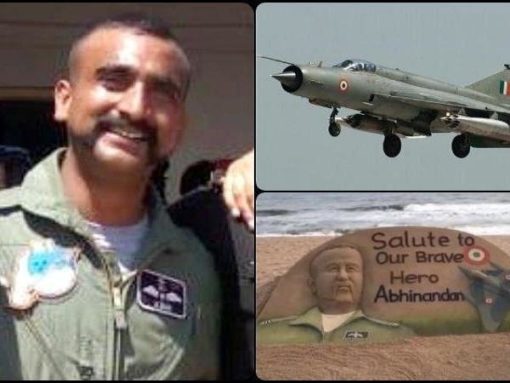

Today, 59 years later, the capture of Indian Mig-21 Bison fighter pilot Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman on Pakistani soil on February 27 is a sombre reminder of how close Powers’ audacious mission, followed by his capture that May Day on Soviet soil, had brought the two Cold War antagonists close to the threat, if not brink, of war. The Soviet Union and the US did not go to war. Two years later, the Soviets returned Powers to America in exchange for one of their prized spies.

But even as some comparisons could be made of the capture of Powers and Abhinandan, there is one crucial difference: while Powers’ mission was planned, the Soviets too were prepared because they had got wind of, and consequently, observed and kept tabs on previous U-2 missions over their territory. On the side, Abhinandan flew into Pakistani airspace by defying orders.

Most of the Indian media, silently backed by the ‘establishment’, spun stories around Abhinandan’s “bravery”. He was turned into an instant icon of Indian air superiority, which was followed by lionisation of a pilot who had “shot down” a Pakistani F-16 before his Mig-21 was allegedly hit by “enemy” missile and brought down. This led to a cinema-like campaign of collective breast-beating, loud and angry denunciation of the Pakistanis and then appeals for his release.

What happened on Indian and Pakistani skies on the morning of February 27 raises important issues regarding unforeseen consequences of actions – individual or collective – that can spark a conflagration between two nuclear-armed states.

While nuclear deterrence would likely prevent both India and Pakistan from escalating, the possibility that even a limited war could break out because of relatively small, insignificant battlefield acts or accidents caused by man or machine cannot be ruled out. It is often said that the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria sparked the Great War of 1914. There is also the example of an “engineered” skirmish on the German-Polish border that caused Adolf Hitler to declare war on his eastern neighbour. The 1961 botched Bay of Pigs invasion and the crisis that followed is yet another instance which brought the US and the USSR dangerously close to an armed conflict.

There is enough evidence to suggest that the so-called “accidental wars” of the last century did not start because of unwise taunts or lunacy of individual soldiers. Wars, usually full-scale wars, often begin as a result of “miscalculations during rising tensions” and, in most cases, the real culprit is a perceived loss of deterrence or when rivals misread each other’s relative military strength. One way a war could start is by a “false alarm”. During the Cold War, many “false alarms” and accidents, ranging from trivial to very serious, have been listed against the US. There were similar mishaps on the Soviet side as well.

It would be instructive to discuss what occurred on February 27 to drive home the point that “individual heroism” could often prove fatal. Much of what happened that morning over Indian and Pakistani skies remains shrouded, not by the fog of war, but by deliberate suppression of facts by both the Indian and Pakistani governments. There is, however, no doubt that the Indian side, backed by a hyper-nationalist and loud media, claimed to have demonstrated air superiority. We need to examine how valid these claims are.

While defence analysts would be better placed to answer these questions, the chain of events that caused Abhinandan and his Mig-21 to cross over into Pakistani airspace must be examined in greater detail. Defence sources have told us that four F-16s (Pakistani forces claim that they were JF-17s of Chinese make and not F-16s) transgressed Indian airspace on the morning of February 27, flying over the Nowshera-Rajouri sector before dropping bombs and then returning to the safety of their own territory. They were given hot chase by Abhinandan’s and another Mig-21 fighter. Further up in the skies, an airborne early warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft within Indian territory watched over the entire battle space.

According to sources, even as Abhinandan’s Mig-21 sped through the skies behind an F-16, a Group Captain in operational command in the AWACS is said to have given him instructions to not cross the LoC. Did he ignore such instructions? Or did he fail to disengage as he was in a dogfight with the F-16? Does the standard operating procedure cover such instances of crossing over into enemy airspace as he was in hot pursuit?

These are questions we need to ask, as the IAF had earlier taken a decision to fire its laser-guided bombs against the Jaish-e-Mohammad terror camp from the Indian side of the LoC. Who then authorised the crossing of the LoC? The second Mig-21 did not cross the LoC and returned to its base in Srinagar.

Questions have also been raised that the F-16s laid a trap to lure Indian aircraft and pursue the F-16s into Pakistani airspace. While Abhinandan is no doubt a talented pilot, did he actually shoot down an F-16? The Indian media has carried stories that Abhinandan shot down an F-16, and its pilot was lynched by a mob in the belief that he was an Indian pilot. Pakistani media have termed this as fake news being circulated by Indian media.

Did Abhinandan fire a missile (supposedly a heat-seeking R-73)? Claims by senior IAF officers such as Air Vice Marshall R G K Kapoor (a transport aircraft pilot) that the Mig-21 flown by Abhinandan shot down an F-16 comes into question because the fighter aircraft would have needed a range of at least 2.5 to 3 km to fire a missile at his intended target. “The reality is that the IAF has no proof of any missile being fired by either of the two Mig-21s,” a senior air force source said.

The jury is out on whether an F-16 was indeed shot down. Just as Pakistan’s story of a second MiG being shot down by it, and coming down on Indian side of the LoC does not have any confirmation. By all accounts that we can verify, there has been no other MiG that was lost in this engagement. Truth, indeed, is the first casualty in the fog of war.

Other questions, however, remain. Was Abhinandan shot down by an F-16 or Pakistani ground fire? The accounts suggest that it was not Pakistani aircraft but its air defence that brought down Abhinandan’s Mig-21.

One enterprising journalist wrote on his personal blog that Abhinandan’s Mig-21 was “struck” by an “AIM-20 AMRAAM missile”, presumably fired from an F-16 that brought him and his jet down. But IAF sources said that “AMRAAM is not a close combat missile. It is a beyond-visual-range missile and firing such a missile with another F-16 nearby (at visual range) could not have been attempted for fear that it could have hit one of their own aircraft”.

Abhinandan conducted himself bravely while in Pakistani custody. Video clips leaked by his Pakistani captors show him speaking coolly and calmly enough and sipping tea that he described as “fantastic”. At home, he was hailed as a brave-heart who engaged in a dogfight with an F-16 and with his Mig-21 before being brought down by aircraft missiles or air defence systems in Pakistani airspace.

Senior IAF sources, both serving and retired, said that Mig-21 Bisons “should not be tasked to chase enemy aircraft” because they are less advanced (from the point of view of speed and avionics) than other Indian fighter aircraft such as the Sukhoi whose fuel capacity is four times—12 tonne—that of a Mig-21 Bison. The Mig-21s, it is said, cannot “turn” as swiftly and dexterously as the Sukhoi-30s and Mirage-2000s. It is unfortunate that a lack of hardened bunkers made the MiG-21 Bisons the only aircraft available to engage the much more sophisticated F-16s on that fateful day.

Already, comparisons have been made between Abhinandan and Flight Lieutenant Kambampati Nachiketa who was taken prisoner of war on May 27, 1999, about a month before the Kargil war, after his Mig-23 aircraft was shot down by a Pakistani ground-to-air missile.

The Abhinandan and Nachiketa examples indicate how decisions – whether in the skies by fighter pilots or on the ground by soldiers – could potentially take countries to the brink of war. The IAF top brass are competent and may even have some degree of “control” over a potentially hostile theatre, but individual actions, the “heat of the moment”, or even circumstances beyond the control of individual pilots, could escalate hostilities to levels that were never planned or anticipated. This is why “controlled” escalation is an oxymoron: it can spiral out of control at any moment.

The history of 20th century wars is replete with such instances that are eminently avoidable, especially in the context of nuclear-armed India and Pakistan. That is why the need for diplomacy. The alternatives are far more dangerous.