"Copies of this Court's judgment in 'Shreya Singhal v. Union of India' [(2015) 5 SCC 1] will be made available by every High Court in this country to all the District Courts."

Agreeing with the suggestion mooted by the Attorney General of India, the Supreme Court has directed all High Courts to make available the copies of the Supreme Court judgment in 'Shreya Singhal v. Union of India' to all the District Courts with eight weeks.

The bench issued these directions while disposing an application filed by Peoples' Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), on the continued use of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act.

The bench also directed the Union Government to make available copies of the said judgment to the Chief Secretaries of all the State Governments and the Union Territories, with eight weeks. "The Chief Secretaries will, in turn, sensitise the police departments in this country by sending copies of this judgment to the Director General of Police in each State, within a period of eight weeks thereafter.", the bench added.

In its petition, PUCL had brought to the notice of the bench that more than 22 people have been prosecuted under the provision, after it was scrapped in 2015. The case was argued by Advocate Sanjay Parikh, who was assisted by Advocates Sanjana Srikumar; Abhinav Sekhri; Apar Gupta and C. Ramesh Kumar, Advocate on Record.

Section 66A

Section 66A was introduced in the Information Technology Act by virtue of an Amendment Act of 2009. The said provision penalised any person who sends, by means of a computer resource or a communication device,— (a) any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character; or (b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device; or (c) any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages. The offence was made punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

Shreya Singhal Judgment

In 2015, the Supreme Court considered a atch of writ petitions challenging Section 66A on the ground that it infringes the fundamental right to free speech and expression and is not saved by any of the eight subjects covered in Article 19(2). The petitioners contended that the causing of annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill-will are all outside the purview of Article 19(2). The bench was also apprised of the fact that large numbers of innocent persons were booked under this section.

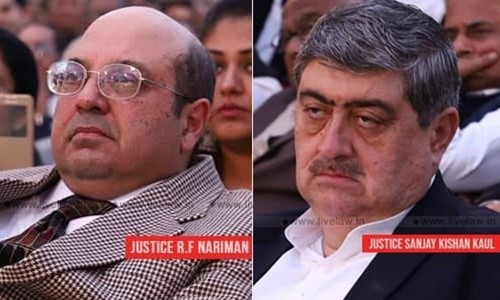

The Apex court bench comprising Justice J. Chelameswar and Justice RF Nariman, struckdown Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 in its entirety, for being violative of Article 19(1)(a) and not saved under Article 19(2).

The court had observed that Section 66A creates an offence which is vague and overbroad. "It takes within its sweep protected speech and speech that is innocent in nature and is liable therefore to be used in such a way as to have a chilling effect on free speech and would, therefore, have to be struck down on the ground of over breadth", Justice Nariman had observed.

"In point of fact, Section 66A is cast so widely that virtually any opinion on any subject would be covered by it, as any serious opinion dissenting with the mores of the day would be caught within its net. Such is the reach of the Section and if it is to withstand the test of constitutionality, the chilling effect on free speech would be total.", the Court had held.

Continued Use of 66A

The Internet Freedom Foundation had released a paper in October last year, claiming that Section 66A continued to be used across India, despite the judgement. The paper, co-authored by Abhinav Sekhri and Apar Gupta, had called Section 66A a "legal zombie", asserting that it haunts to Indian criminal process, despite more than three years having passed since the judgment. It had argued that this was because of deeper institutional problems which resulted in judicial decisions not reaching state actors at the ground level. "Right from the police station, to trial courts, and all the way to High Courts, one finds that Section 66-A is still in use despite it being denied a place on the statute book," the study had said.