Aamer Hussein is a short story writer and critic. Born in 1955, Hussein grew up in Karachi, spent most of his summers in Indore, studied in Ooty for two years, and moved to London in 1970. He has written several collections of short stories, including Mirror to the Sun (1993) and Insomnia (2007). He has also written a novella titled Another Gulmohar Tree (2009) and a novel, The Cloud Messenger (2011). Hermitage is his latest collection of short stories, which, as Bina Shah puts it, “delve into the realms of mythology and the metaphysical…his language is that of myth and legend, and in interpreting the symbols and signs of his own parlance, he helps us understand our own…”

In this conversation with Daniya Rahman, Hussein talks about Hermitage, why he prefers writing short stories, the question of translatability and much more.

Daniya Rahman (DR): Your stories are interspersed with moments of history, family memories, and retelling of classic parables and this is a very conscious choice. Can you talk about your style of writing, the journey of how you acquired this style? Why short stories specifically?

Aamer Hussein (AH): I began in the way that most apprentice writers do, by writing stories inspired by my own immediate surroundings and the places of my past, but my real attraction from the start was to the fabular and the parabolic – what we might define as tales, rather than stories, eg. the work of Isak Dinesen, Tanizaki, Borges and Youcenar. However, to develop the detached impersonal voice that tales require took me time, as I was also drawn in by intimacy and the tangles of psychology. As I wrote on, I began to juggle historical moments with what you call classic parables, particularly when, about 15 years ago as I worked on own favourite book, Insomnia, I came across the writings of Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch, a brilliant French scholar of Islamic mysticism. She was best known for her prose translations of Rumi and Iqbal, though her range was in reality much wider. It occurred to me then that the classic tales I’d taken for granted needed very little in the way of embellishment to be retold in simple English prose.

I want my collections to be eclectic, to take you on a journey most novels can’t, from places of the mind and heart to imaginary lands and lost worlds and back. My style is eclectic, too, as it is influenced by different genres and particularly by music and poetry. As for my choice of the short story, it was what I preferred as a young reader, and to begin with, it was easier to complete a few short fictions than the two novels I struggled with (both of which eventually became long short stories, to use that tautological description). Until I was finally inclined to write a novella followed by a novel in my 50s, I had remained dedicated to the form as a practitioner. Paradoxically, writing that novel nearly a decade ago made return to my preferred form with new vigour, with the difference that my stories became shorter still, and my range of interests wider, so here we are, back at the beginning of your question.

DR: You have used photographs to add a visual background, as it were, to the stories in Hermitage. I’ve always believed that photographs are capable of telling stories. Photographs freeze a moment and at the same time, make it eternal. Your stories are already very visual in nature, what was the thought behind adding photographs to these stories?

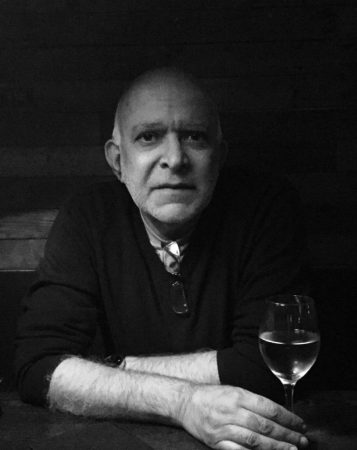

AH: I wish I could lay claim to that idea! A collaborative piece in a previous collection used photographs of a trip to Andalusia taken by Alev Adil, the co-author; and a year later, when poet and publisher Leona Medlin asked if I’d work on a miniature book of stories (Love and it Seasons) for her Mulfran press, she also suggested we use some colour photographs I’d taken on my phone as a visual diary on my London walks and other journeys, to give the collection contrast and vitality. We couldn’t use the story I mentioned for copyright reasons. Eventually, we selected a variety of images, including artworks by young artists from Karachi and Dhaka. My new Pakistani publisher, Shahbano Alvi, is herself an artist and designer, and suggested a full-length collection for Pakistan with a different set of black and white images, which include photos by myself and also by Shahbano, and by two young writers from Kashmir, which as you say freeze moments and make them eternal. I think my publisher/editors and I would agree that we chose images to add a counterpoint to the texts and to signal continuities across eras, rather than to illustrate the stories in a conventional sense. Though we do have a picture of my mother, and in my author portrait on the back cover I’m backed by the Karachi sea, so there’s a documentary element included too.

DR: What does home mean to you as a writer and as somebody who has lived in many places?

AH: As a writer, and as I grow older, home reflects the axis of my life today: Karachi, which is not just my native city but the place where, for the last decade, I’ve done much of my most significant work, and London where I came of age, studied, and published my first fictions and then a book, long before the subcontinent recognised me. There’s also the influence of my maternal family’s homes in Malwa, India, which as a teenager I knew much better than my father’s Sindh (where I’ve recently, finally travelled). And the fact that I come from a family divided by borders and how difficult it is to visit India, which has published almost all my books from the second one onwards, But I’ve spent almost all my adult life here in Little Venice, London, and I sometimes think this physical rootedness allows me to travel frequently both physically and mentally. In Karachi, I now stay in a private club. The irony is that travel seems to feature more in my writing than home, wouldn’t you say?

DR: The stories in Hermitage move across not just multiple spaces but also languages. Do you think this multilingualism has helped your writing? How?

AH: Quite literally, two of the stories are translated from my original Urdu versions. But much more importantly than that, stories like “Dove” and “The Life and Death of a Poet” are about Ada Jafarey and Shefta, two Urdu poets belonging to two different centuries, whose lives span not just a century and a half of Indo-Pak history, but the development of a language and an anti-colonial mindset. I wouldn’t have come upon these accounts had I not been an inveterate reader of Urdu: in fact, it was Ghazalnuma, an anthology of poems edited by Ada Jafarey that led me back to the facts of Shefta’s eventful life. There’s the Hindi ballad of Daya Gujar which I gloss in another piece; certainly not the sort of material anglophone writers usually use. Then there are Attar and Rumi’s parables, which I think cast their light on the entire collection, that I read in Persian verse and French prose versions, bypassing entirely my two natural languages. More literally, my early prose style, which reminds some people of Urdu though I was hardly well-versed in Urdu fiction at the time, was hugely helped by my readings of French fictions in the original language. In Hermitage, though, the influence of Urdu and Persian is evident.

DR: The story “Annie” seems to blur the distinction between fiction and non-fiction. It is a personal account but seamlessly fits in with the other stories. What do you have to say about this?

AH: It was only after Hermitage was published that this point about the generic interface in “Annie” was brought up by the critic Muneeza Shamsie, among others – it was written as a documentary account with no inventions or embroidery. But memory and its vagaries shape our writing, and I imagine the reconstruction of remembered dialogue here is a fictional technique that helps to blur distinctions. My publisher, as far as I remember, wanted to include it, to my delight, I thought that including non-fiction was a risk worth taking in a book that draws so much upon life. There are precedents in Urdu of writers slipping brief memoirs into their collections (Ismat Chughtai, for example). Annie Hyder herself used sophisticated novelistic techniques in her autobiographical volumes, Kaar e jahaan daraaz hai, so obviously she was a forerunner I was aware of. Flattered as I am, I confess I didn’t intend to blur boundaries, though I did primarily want to narrate the long story of a friendship. A memoirist can also be a storyteller.

DR: The emotions we feel and the attachment we have for our families, often makes it challenging to write or talk about. You’ve written the “Lady of the Lotus” taking from your mother’s diaries. Can you talk about the experience of writing this story?

AH: My mother handed me her diary (which I’ve used, I believe, in its entirety) about 21 years ago, but it wasn’t until 2016 that I was able to decide how to use to use it without plagiarising or ‘stealing’ her voice. One day it suddenly occurred to me that if I transcribed her writing word for word but in the third person, interspersed it with her children’s comments, and her own voice, we’d have a new piece entirely. I took me about a day and the day was an epiphany. I haven’t had to edit her prose at all, and there are quotes in the story I took from her at the time of writing. However, she firmly refused to be acknowledged as co-author, though she does take credit for her translation of “Bridges”, and all of her maternal uncle Rafi’s story was told to me by her, so added to the other genres in the book there’s also oral history and yes, the question of what can and can’t be told is a challenge when you aren’t presenting it as invention. In fact, as our conversation reveals, the subtext of this book is really about collective authorship; there’s almost nothing here I can claim as exclusively my own, as even the most intimate of the stories, “The Wounded Swan”, is brought to the reader in translation.

DR: You also write in Urdu, how do you find Urdu as a language to write in?

AH: I have witten six pieces in Urdu, the first five over less than a month in 2012 and the last one in 2014. It was an exercise in delight as I’d really never thought I’d complete anything in my language. I was given a challenge by a poet friend who said I should write in the simple everyday language I speak and I thought, why not try a very short piece? It flowed, but it was anything but simple – as I wrote, the echoes of half-remembered Persian and Urdu poems and a vocabulary drawn from Hindi too found their way to the page as I wrote by hand. Everything I miss in my borrowed language is available to me in Urdu. What wasn’t present was the influence of English; I would see as in a film what I wanted to narrate and pluck the right words from the air. After two short pieces, written in one sitting, came an essay and two long stories, and I experimented with style and dialogue, overcoming the problem many of us have in conveying vernacular speech in English. The greatest praise, perhaps, came when the genius of the Urdu short story, Intizar Hussain, complimented my work and also commented wryly that while others were rushing towards English I’d made a return journey to my mother tongue.

DR: How true to the original, do you think a translated version of any work is?

AH: It depends entirely on the language. French to English or Persian to Urdu or Punjabi to Hindi is, for example, easy enough. I’ve found that Persian and the subcontinental languages I know don’t transfer well into English. It’s a question both of melody and of idiom; you lose one or the other and at times both. Poetry is nearly impossible; I’ve rarely seen a translation of a ghazal which retains rhyme and metre and still works as an aesthetic object. Prose should be better, though recently I read some translations of Ismat Chughtai with a class, comparing versions by two different translators; they might have been different stories altogether, as each translator had cast the story in his/her own paricular idiom.

My own English stories read very well in their Italian versions, but I interfered a fair amount in the process. Of my own Urdu stories, two were ‘Englished’ by a collaborator who knew no Urdu, from literal versions by me; two were translated by my mother; and one by Shahbano Alvi. The first two seem faithful to me, but I can’t say much because I see my own hand in them. Mother recast one entirely with my approval, so it’s a free translation that retains all the humour of the original tale; the other, “Bridges”, sounds exactly like my work in English though she made some cuts.

DR: Being a translator yourself, what do you think are the challenges you face, if any, while translating from Urdu to English?

AH: Interested as I am in the question, I’m not a translator by any means, because while I’d like to be true to the original I’d end up rewriting it; I’ve probably worked on translating about three texts in my life and been accused of taking liberties with two of them. I don’t think of my Attar or Rumi fables as translations, but as very faithful retellings, as their austerity needs no decoration. But here I can recount the story of a story. When I tried to translate my own story “Maya or Hans” into English it soon became something quite different and lost its original dramatic and somewhat surreal conclusion for something more throwaway. Finally it was translated by Shahbano last year; I think her translation, “The Wounded Swan”, is very close to the original, though evidently, certain word choices had to be agreed upon; it’s hard to retain the lyricism of one language in another, but the strength of her translation is that it captures the mythological dimension as well as the bird and water imagery of the story’s key passages.

DR: You’ve been at and experienced multiple places and as you said, you travel quite frequently, have you considered writing a travelogue or may be an autobiography, perhaps in the form of short standalone and yet interconnected narratives?

AH: I write columns for the book pages of DAWN, the leading Karachi daily, many of which have a travel element, including one about a trip I made to Palestine in 2013. I somehow don’t think they’d add up to a book. Odd you should say that about an autobiography, though, because that’s exactly the form that I envisage, a kind of ‘Six Chapters of a Floating Life’, to steal the title of a Chinese classic. Maybe in a year or so, once I’ve consigned the stories jostling for space in my head to the page (or screen).