Edited by Gopalkrishna Gandhi, The Oxford India Gandhi: Essential Writings tells Gandhi’s story in his own words. Gandhi’s writings—in the form of speeches and articles, and also the more informal diary entries, letters, and conversations—unfold chronologically, the unexplored facets of his evolving world view, his responses to persons and events, and his relationships with family, friends, and colleagues. Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s general and part introductions locate these writings in their proper context. The following are excerpts from the chapter “The End of an Epoch” of the book.

To the tension between India and Pakistan was now added the issue of Pakistan’s share of the cash balances of undivided India amounting to Rupees 55 crore. On the ground that this money would provide Pakistan the sinews of war to be used against the Indian Union on the Kashmir soil, the Government of India deferred the payment of the amount.

Gandhi discussed the question with Lord Mountbatten on the 6 January 1948, and asked for his frank and candid opinion on the Government of India’s decision. Mountbatten said, it would be the ‘first dishonourable act’ by the Indian Union government if the payment of the cash balance claimed by Pakistan was withheld. This set Gandhi thinking. He would have to, he felt, have to create a new moral climate.

Gandhiji had decided to launch on a fast unto death. …

… A pure fast, like duty, is its own reward. I do not embark upon it for the sake of the result it may bring. I do so because I must. Hence I urge everybody dispassionately to examine the purpose and let me die, if I must in peace which I hope is ensured. Death for me would be a glorious deliverance rather than that I should be a helpless witness of the destruction of India, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Islam. That destruction is certain if Pakistan ensures no equality of status and security of life and property for all professing the various faiths of the world and if India copies her. Only then Islam dies in the two Indias, not in the world. But Hinduism and Sikhism have no world outside India.

P, MG: LP Vol. II, pp. 702–3

Devadas … made an impassioned attempt to dissuade him from the grave decision through a note which he drafted. The note ran: ‘My chief concern and my argument against your fast is that you have surrendered to impatience, whereas your mission by its very nature calls for infinite patience. You do not seem to have realized what a tremendous success your patient labour has achieved. It has saved … thousands of lives and may still save many more. … By your death you will not be able to accomplish what you can by living. I would, therefore, beseech you to pay heed to my entreaty and give up your decision to fast.’

Gandhiji replied to Devadas:

… You are of course a friend and a friend of a very high order at that. But you cannot get over the son in you. Your concern is natural and I respect it. But your argument betrays impatience and superficial thinking … I regard this step of mine as the acme of patience. Is patience which kills its very object patience or fully? I cannot accept the credit for what has been achieved since my arrival in Delhi. It would be sheer conceit on my part to do so. How can any mortal say with assurance that so many lives were saved as a result of his or anyone’s labours? God alone could do that …

… Your last sentence is a charming token of your affection. But your affection is rooted in attachment or delusion. Attachment does not become enlightenment because it relates to a public cause. So long as one has not shed all attachment and learnt to regard both life and death as same, it would be idle to pretend that he wants to live only because his life is indispensable for a certain cause. ‘Strive while you live’ is a beautiful saying, but there is a hiatus in it. Striving has to be in the spirit of detachment. Now perhaps you will understand why I cannot comply with your request. God sent this fast. He alone will end it, if and when He wills. In the meantime it behoves you, me, and everybody to have faith that it is equally well whether He preserves my life or ends it, and to act accordingly. I can therefore, only pray that He may lend strength to my spirit lest the desire to live may tempt me to a premature termination of my fast.

P, MG: LP Vol. II, pp. 703–5

[…]

Rajmohan Gandhi concludes in The Good Boatman redemptively thus (pp. 436–8):

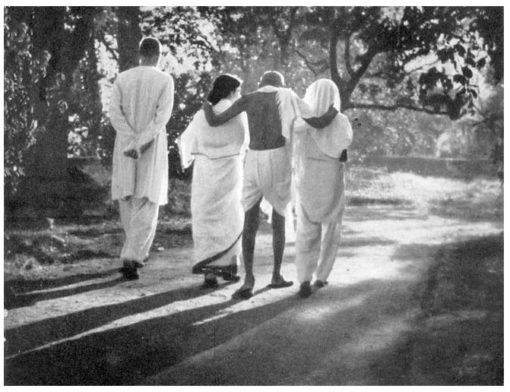

With this the three and those walking behind them fell into a complete silence, for they had reached the five curved steps that gently led up to the open prayer ground. It was Gandhi’s stipulation that small talk and laughter had to cease, and all thoughts turn to their sacred purpose, before they put their feet on the prayer site.

Behind their backs the winter sun was setting. A 32-yard path lay between the steps and the platform where Gandhi used to sit for the prayers. The women and men who had come for the prayers lined the path on both sides. Removing his hands from the shoulders of the girls, Gandhi brought them together to acknowledge the greetings of the congregation.

From the side to the left of Gandhi, Nathuram Godse of Pune roughly elbowed his way towards him. Godse had been on the scene ten days earlier for the abortive attempt to kill Gandhi, had slipped away, travelled to Bombay, and returned with a fresh plan of assassination. Thinking that Godse intended to touch Gandhi’s feet, Manu asked Godse not to interrupt Gandhi, added that they were late already, and tried to thrust back Godse’s hand.

Godse violently pushed Manu aside, causing the Book of Ashram Prayer Songs and Gandhi’s rosary that she was carrying to fall to the ground. As she bent down to pick the things up, Godse planted himself in front of Gandhi, pulled out a pistol and fired three shots in rapid succession, one into Gandhi’s stomach and two into his chest.

The sound ‘Rama’ escaped twice from Gandhi’s throat, crimson spread across his white clothes, the hands raised in the gesture of greeting which was also the gesture of prayer and of goodwill dropped down, and the limp body sank softly to the ground. As he fell, Abha caught Gandhi’s head in her hands and sat down with it.

Always a sharp observer and well aware, as we have seen, of a conspiracy aimed at his life, Gandhi may have perceived Godse’s intention before seeing the pistol in his hand. We will never know for certain whether he forgave Godse before life left him, but his mind was on prayer when he was shot and he had prayed earlier to be able to forgive his assassin.

A haste to pray. A hush on entering holy ground. A sense of the Eternal. Lines of fellow-worshippers. A gesture of goodwill. Rude elbows. A smell of attack. The ring of three bullets. ‘God! God!’ Possibly a silent, ‘God! Forgive them.’ Loving hands underneath. Earth, moisture, grass. The open sky. Rays from the dipping sun. A perfect death.

Read More:

Gandhi’s Last Fast

Prof. Irfan Habib on ‘Mahatma Gandhi and the Concept of Nation’: Lecture Organised by SAHMAT

Is Today’s India a Threat to Gandhi and Ambedkar’s Idea of a Secular Nation?