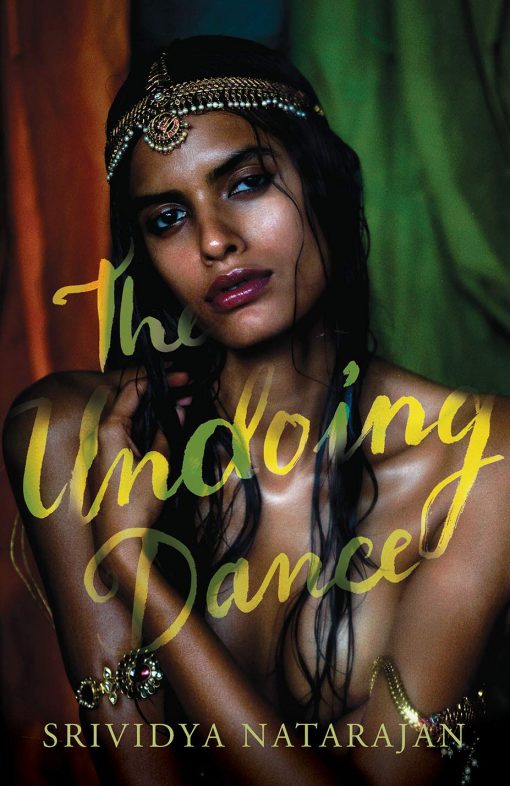

Written by Srividya Natarajan, The Undoing Dance is the story of Kalyani, a woman who comes from a lineage of famous devadasis. The devadasis were once celebrated as artists, but are shunned as ‘prostitutes’ in a newly independent India. The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Kalyani” of the book.

When I came back from the mission house, after more than a decade of being away from Kalyanikkarai, I avoided my old acquaintances. A chasm had opened between the girl I was when I belonged to them and the woman I had become after years of belonging to Aunt Rachel. All my life since then I have built frail notional bridges from past to present, from one self to the other, and have not expected them to bear me safely across the gap.

I had built up hopes of being a school teacher, with my English education, and at first, the Kalyanikkarai Government Elementary School showed interest when I applied for a job. Then the headmaster heard that I was a dasi’s daughter, and the school closed its doors to me. There was a shop on East Main Street near the temple’s south gopuram that sold things used for worship: kungumam powder, turmeric, clay dolls of gods, brassware for rituals. The owner needed someone to sit in the shop in the mornings when there was not much business. My wages reflected this, but I was glad to have a job.

One evening, two months after I had come back, I met Velu Vathyar on Musicians’ Street. ‘So you’ve done all right for yourself,’ Velu Vathyar said. ‘Never came to see us. Not once.’

‘Aunt Rachel – Kokku Missy – would not let me.’

‘She was not watching you when you came here. You should have come to see us at least, even if you didn’t want to come back to dance. My father missed you. He is a sick man now.’

I hung my head. It was indeed shameful that I had not visited Samu Vathyar when he was ill, and he on the same street as us. It was impossible to explain the strain and disturbance of moving between those worlds, my mother’s and Aunt Rachel’s; to explain the inertia that made me long to remain in one element and one world for a stretch of time.

‘So,’ Velu Vathyar said, ‘why are you back now?’

‘I’m back home for good. Aunt Rachel’s nephew came and took her away to Australia.’

‘Are you coming back to dance?’

‘I never thought about it.’

‘Come back and learn,’ he said. ‘It will please my father.’

I went to see Samu Vathyar after work that evening. He lay on a string cot, a gaunt old man. His ribcage expanded and contracted with each breath he laboured to take. He peered at me, not looking in the least bit pleased.

‘Why did you not train to be a school teacher?’ he growled. He was as terrifying as ever, even with his vision almost completely gone now. The ripe opaque cores of his cataracts were visible in his irises. ‘Eh? Why come back to this?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said.

‘Hmm. Tuck your sari up and get in position,’ he said. ‘Let’s see if you have any talent left.’

I began to dance again.

Over the next few weeks, Samu Vathyar taught me a new varnam. The absence of people (his wife had died, his girls had married and gone away) in the booming hall made his tapping-stick sound hollow. Velu brought him food, changed his clothes, plumped his pillows, fetched the doctor. He taught the younger students their steps. There were brahmin girls in the class now, smug and thin-lipped. There was need for their money and their goodwill. They brought their own water, to stave off the pollution of quenching their thirst in the home of a nattuvanar, so many rungs lower than them on the caste ladder.

The control of the traditional masters was worn away by this difference in caste. The new pupils danced indifferently. Since Velu Vathyar knew quite well that neither they nor their parents would tolerate the old pedagogy – the sticks flung at the stumbling legs, the dancing for hours without a break, the curses and insults – he developed a sort of ferocious patience. He withheld the best dances from the brahmin girls. He filled his mouth with betel leaf and betel nut. When he could not bear to teach, he went out and spat noisily into the drain. His betel-chewing was an insult.

I had to wait for my lesson until the brahmin girls had finished and left. If I lost my balance or moved clumsily, Velu was foul-mouthed. My shani, my curse, he cried, mocking me because he could not mock the brahmin girls. Gnanasoonyam, ignoramus. I tried on the movements he taught me, tried on the mind that went with such movements, the ethos that had produced them. Growing up as Callie, I had not learned what Kalyani would have learned by instinct, by osmosis: how to love, how to respect, how to seduce, how to insult, how to walk, how to spit, how to make a bed, how to pick flowers, how to count money, how to hate. I felt as square and angular as furniture; as wooden. My arms felt unfamiliar. I felt discomfort in every one of my tight muscles.

I learned the gestures for the varnam: a woman preparing a bed with flowers; a woman pointing to her own breasts that were heavy with desire; a woman sending her parrot to her lover, with a message. Of course I had danced a varnam at my arangetram, but that was before I knew the meanings of the lyrics. I want to make love to you, lord of the fifty-four kingdoms on the banks of the Kalyani.

If I hesitated before the sexual explicitness of the gestures, Velu’s mouth became wry. ‘So you’ve learned this from your white Christian Mamma,’ he would say. ‘So you can’t make the bed to receive your lover or describe the beauty of a woman’s breasts any more.’

How did my mother dance so differently from me?

Her dance was part enactment (so remote, so ritualized, the neck flicking lightly from side to side, keeping the beat, no vulgar grasping at the real), and part conversation (so easy, so natural, like talking to one’s cook or one’s husband). I had to act. All the dancers in the class now were acting their emotions; they had been watching the way actors emoted in the movies; they didn’t know how to enact anything. How? I thought, envious, thrashing about in my body, how did my mother do that?

But the world that had called for enactment was obliterated. It was dead already, though I tried to revive it in my body.

After many months of dancing with Samu Vathyar and Velu, I began again to feel the fluency of my body. When I had been a child, I had danced what I was told to dance; now I understood more about the composition of each piece, about music and rhythms, and about teaching dance so that it was subtly adapted to the body or the personality of the student. I began to teach the younger children in Velu’s class, and I took a small share of their fees home. I still worked at the shop. Th e money helped my mother and me survive from month to month. The only other income was rent from a portion of the house which had been sectioned off , if I remember right, the year I began to dance.

Samu Vathyar died in his sleep one summer night. Velu Vathyar continued to teach me. His hand had begun to shake when he wrote down the notation for a song. Wasn’t he, I wondered, too young for that? The tremor would roll down his fi ngers into the curlicues of his thadinginathom in Tamil, making the letters hard to read. I had not read Tamil for years. Now I could read it well enough when it was printed, but I slowed down when it was hand-written. He lost his temper when I could not decipher his notation for the songs I was learning. He blamed my Christian Mamma.

When he taught me, I was compelled to give the dance everything I had. Th e hollows of my neck became cups of sweat; my muscles, even though they were supple again, ached. With me, he still enforced discipline of the old-fashioned kind. Not the kind that the modern individual would tolerate, but the kind that broke down the self to reveal the dancer, some grander, stronger force than the self, all hamstrings and energy, all seduction and poetic intuition, underneath. He was the medium of my surrender to something transcendent, apart from myself. I needed him, for I had been taught too much individuality by Aunt Rachel, and I did not know how to exercise my craft simply and directly, without the veils of analysis, timidity, moral doubt.

It was almost logical for a woman whose art did not flow unimpeded by self towards god or king or world, the way my mother’s had done, but needed a human medium; it was almost logical, I realize now, to take her master for her god, and then by degrees for her lover. Years of searching his face for infinitesimal signs of approval, years of waiting patiently as he tapped out combinations of steps with one hand, kept time with the other.

The universe had to be pared down to this: a leg stretched just so, a movement of the hands so precise it was a stillness in the movement of the world. My feet described clean squares and perfect circles. The expressiveness, the emotion, they had to come from passion that was deeper than geometry, and Velu was there, the water that wore down the rock of my self.

Until I married Balan, everything I really knew, deeply, everything that accorded with my impulses and felt agreeable to my body, came from Samu Vathyar and Velu Vathyar. When I came back from the mission house, and for years afterwards, when I thought of Velu, I could have wept with gratitude. I actually did weep when I was feeling volatile. Watching Hema struggle with her loathing of Padmasini, I was often on the verge of telling her what a teacher might be to a student.

And what was I to Velu? Th e complex combination of rhythms he thought up needed a body to bring them to fruition.

In that empathy – in that moment of being the female body which would interpret and complete the man’s creation – love was easy, inevitable.

Read More:

From the Salon to the Studio

The Syncretic History of Music in India