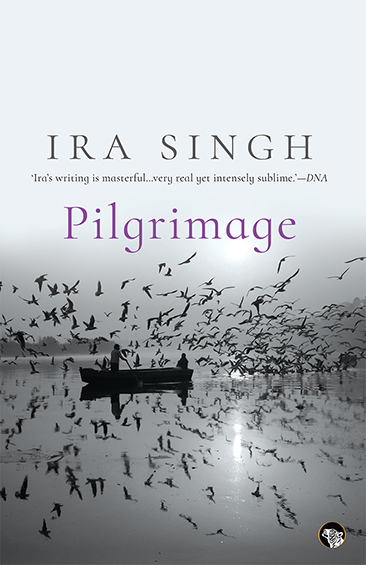

Written by Ira Singh, Pilgrimage tells the story of Monica or Mona, who belongs to western Uttar Pradesh, through three phases of her life. The three sections of the book, titled “Pilgrimage”, “Transgressions” and “Punishment” take the readers on a journey through her life in reverse, unearthing how the life of a woman transforms from the 1980s to present-day India. The following is an extract from the section “Pilgrimage” of the book.

She sees her father strapped down on a gurney, face covered by the mask of a portable ventilator, blood blooming along the path of the hastily inserted tube in his wrist, life beating erratic, quick, at his neck; the nurse, muttering into his cell phone, jiggling the stand to which the drip is connected; she hears the slosh-slosh of urine in the plastic bag on the side of the gurney, hears her mother’s prayers.

Her cell phone rings. It is Vicky,her brother,in a panic; he will take the first flight he can get, he says. She talks calmly about the situation, she reassures him.

Her phone rings again; a relative, bemoaning the fact that her brother isn’t here to do his duty.

The driver stops for a pee, apologetically. She emerges, too, from the back of the hard-benched brutal interior of the vehicle for a minute, looking anxiously over her shoulder, cell phone to her ear.The air hits her face, moist and smelling richly of cow dung. Dogs, yammering, slink into the shadows. The relative talks on. She is exhorted to be calm, philosophical and wise, to believe in the power of the Almighty.

Devotees roar past. They are called kanwariyas. In this season, the season of rain, in a month named after the rain, they walk down highways with gaudy tinsel-covered pots of holy water strapped across their shoulders.They are worshippers of Shiva and must, at the end of their arduous journey, empty these laden pots at their village temples, please the god with their fervour.

They have been seen for years on this route; stork-like they’d made their way, flash of bony legs and rain pouring down upon them they balanced their loads and walked on.

Now they race past, waving saffron flags.

She sees, in quick succession, men on a pair of motorbikes with no silencers, yelling, a tempo with flashing lights atop and then a decorated truck, two glittering mini temples inside and devotees trudging alongside, streamers floating behind, a diesel genset packed into its roomy interior and a disco beat thumping, its volume ratcheted up.

She gets into the ambulance,the air-conditioning envelops her, neon within. It is considered state of the art: shiny, stocked with gleaming gadgets, expensive to hire, the first of its kind in the small town they have come from.This desperate journey to the city was the result of a doctor’s pronouncement in an ill-equipped hospital; he said he needed his sole working ventilator for a burn victim, a young man whose wife, two small children and dazed old parents were huddled outside, sobbing.The implication was obvious, her father was not needed in this world the way the young man was, bandages on his bare muscular chest, eyes taped shut.

[…]

Increasingly the landscape of these great dusty highways is dominated by saffron, the colour of a faith. On the broken-down walls at the edges of fields fringed by ragged rows of eucalyptus, there have always been hastily scrawled invocations, on billboards and pillars pictures of saints and the gods, holy men’s discourses blaring from podiums and TVs, always those makeshift shrines with diyas flickering below peepal trees and labyrinthine processions carrying statues of decorated deities to the rivers.

All that magnified, exaggerated, distorted. She has seen camps that seek to make kanwariyas comfortable, they are given food and drink, shelter, they are given respect; loud speakers, triumphal fervour, the piety and obeisance of people, and plastic waste, mark these camps.

She has seen those other camps, too, the camps of refugees from the tall fields of Muzaffarnagar not that long ago, tarpaulin blue and flapping and thick mud everywhere as children, uncharacteristically quiet, played, women, bewildered, wept, and young men [impotent, uncertain] talked wildly of revenge. Old men gathered and talked of compensation.

They talked of citizenship.

[…]

They come, suddenly, to a halt.The road ahead is blocked.The driver turns on his wailer.The dense stretch turns out to be a collection of vehicles inching along, packed with kanwariyas dancing to loud disco bhajans. Some run behind each truck, carrying batons and bottles of water, daak kanwariyas, postmen.They are unmoved by the high-pitched yowling of the ambulance, this tone that signifies impending doom. Its noise is drowned out by theirs [deafening, unapologetic].

Young men, half naked, dance. They wear baggy shorts, track pants, orange lungis.Their T-shirts proclaim Bum Bhole and Bhole Nath, in praise of the god, they wave the tricolour and shout Bharat Maata ki Jai, in praise of the motherland. Saffron banners flutter in the meagre night air. Each banner speaks of origins, of the village, the place from which these particular young men have journeyed, how far they have come on their quest.

The driver turns to her, he pushes open the connecting window, the nurse shaken out of his WhatsApp-induced stupor. Her mother comes out of the trance of prayer.The driver calls her mataji.

We can’t move them, the driver says to all of them worriedly.They don’t like interference.

Their shivir has been set up nearby, that’s why they are moving so slowly now.

He means their camp, where they will have their feet massaged by willing volunteers, where they will be assured by the minions of the state that they are protected admired revered.

He says a riot is possible if they are moved. The word danga, riot, fills her with alarm.

She watches the appalling spectacle, momentarily outside the increasing urgency of the situation.

The driver says tenderly, watching them dance, [hockey sticks in their hands] poor things. Many die on this pilgrimage every year. They are killed by speeding trucks and cars, by Mohammedans too, deliberately.

She interrupts him rudely, snapping back into the moment. She cannot listen to this.

You need to move them, she says.

They are doing the work of God, he continues to muse, why blame them, how is it their fault, they go to get that sacred water and they walk barefoot, on stones and through the dust of highways,through fields,they travel only in worship, to fulfil their vows. Mohammedans wire their fields and the current kills these poor boys when they pass through.That is why they have started using trucks to travel, because of these people.

My father will die, she says, now not listening to this casual, unconscious venom, not even, anymore, responding to it.

The driver is a good man, she is sure of that, he understands suffering,he will help her.

My father will die if we don’t reach the hospital soon, she says again. Please do something.

The driver gets down, he goes towards the men.

She finds she is weeping again, she has uttered the word death and it has become real, she imagines her father unmoving, without breath or blood.

Their journey has ground to a halt in front of the faithful; the beat gets louder, every surface nearby rings, vibrates from the noise.

A hot thin moon rides above them.

The road is lit up by neon from their portable generator, the air thick with diesel fumes, they are producing electricity, consuming it, they are suficient unto themselves, their lives till now [unremarked, unredeemed] pure in these moments of elevation.

She watches the driver reason with the leader of the young men, who has hopped off a motorbike and who wears an orange T-shirt with a matching pair of shorts. It is obvious he wears no underwear.

He wears sneakers.

[Weren’t they supposed to be barefoot? Weren’t they supposed to suffer?]

The young man gesticulates angrily. The driver folds his hands. She sees before her, in gestures, a drama of supplication and appeasement.

Her mother says, from the back, Mona. She gets down. She marches towards the

man, who turns and stares.

It must be her cropped hair, her jeans and shirt, she thinks, she is used to the staring.

She must make him understand.The driver says to her, madam, go back, he will not listen to you. His voice is raised. Perforce.

She says in a rusty imperious voice, tears banished now, falling into a recognizable idiom, my father is critical. Let the ambulance go past. This head gyrator, mechanically touching his lips and forehead in a superstitious gesture, implores her to speak only of good fortune, Shubh shubh bolo, he says.

She says, urgently, we have to go to the hospital.

He gestures at his comrades, in motion, ostensibly lost in worship.

I cannot do anything Aunty, he says.

He wears a sacred thread on his brawny wrist, a holy smear on his forehead.

He turns away.

Absurdly, she finds herself as offended by the appellation as by the gesture.

She grabs his arm. It is tattooed, inked with portraits of armed goddesses. They leap out at her, blue in the lurid glare. She has never touched a working-class man before. He shakes her hand off roughly, clearly not electrified by her touch, seeing it, evidently, as a breach of propriety.

She says, holding her phone up, I will WhatsApp your photo to the media. Everyone will know you stopped a man from reaching the hospital, you denied him treatment. Is this your religion?

The rhetoric comes unbidden to her lips. The nurse looks impressed. He has hopped out of the ambulance. The machines are on within, hissing, rattling.

The kanwariya pauses in turning away.The word religion, it seems, signifies only authority [brazen, brassy].The word media holds for him, though, a multitude of meanings.