Vikram Sonare, son of a debt-laden farmer who commits suicide and Mallika Joshi who works for an NGO, embark on an epic mission after they meet in Vidarbha, to draw attention to the plight of farmers and other underprivileged sections of society, and finally mobilise millions of people to march into the major cities of India. After the success of the march, the group transforms into a revolutionary political party. But will the existing political forces allow it to succeed?

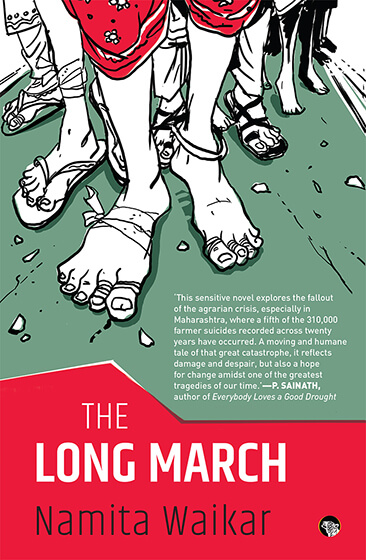

Urgent and inspiring, Namita Waikar’s The Long March is a necessary story for our time. The following is an excerpt from the book.

Bundles of Firewood and Fistfuls of Fodder

Readjusting the sari over her head, Kashibai peered around the shops. But her husband was not to be seen anywhere. She hastened to the cowshed. He was not there either. Just as she turned to leave, her eyes darted back, catching sight of something at the deep end of the little enclosure. Toes…Feet…? Her husband’s familiar gnarled feet! She called out to him, ‘Aaa…ho…!’ and the next instant shouted out to her son, ‘Vishwaa…aaas!’ as she ran inside. She felt her heart thumping, the beat filling her ears. He was on the ground, stretched out near a pile of hay. Next to him was a can of pesticide. Hands at his sides, palms open, he lay lifeless. His eyes were closed and his head was turned a little away towards the wall of the cowshed. Kailashnath’s ashen face was vacant of the worries that had pinched it the night before.

Vishwas and Surekha came running into the cow. Followed by Nilesh, who was rubbing his running nose on the sleeve of his T-shirt, a birthday gift from his grandfather from last year. On seeing her father-in-law on the ground, Surekha silently took Nilesh out of the cowshed, tears streaming down her cheeks. Vishwas crouched next to his father. He picked up a scroll of paper that seemed to have rolled out of his father’s open palm. It was a stamp paper. A hundred-rupee, non-judicial stamp paper. A letter on the stamp paper was addressed to the village sarpanch, Maharashtra, the Agriculture Minister, the Prime Minnister, and the president of India…surely, at least one of the recipients would listen to his plea:

Please take note of my plight. I had taken a loan of Rs 45,000 from the Status Bank of India. I cannot repay the loan or the interest because there has been no rain again this year and my crop has failed a second time. The people from the bank have come to our house three times to ask us to repay the debt. They will come again to ask my wife, my son, and my daughter-in-law to pay the loan amounts that they have also taken. Please spare them any harassment. If they get a good harvest and are able to repay, they will clear the debt. We are not bad people. We do not want to swindle money from the bank. But if we just do not make enough money to repay the loan, I request you to give us more time or waive the loan. I do not want my family to meet the same fate as mine. Please let them live in peace.

The villagers gathered and crowded in the cowshed. Kashibai’s eyes were dry. Only one thought occupied her mind: his worries were all over and now she had both his and her share of worrying to do. Before her tearless eyes, all she could see was her family: Vikram and Vishwas, little Nilesh, Surekha and the one growing in her womb. Kashibai must now worry alone for all of them. She was head of the family now and they were all her responsibility.

And They March In

The morning had brought the city of Mumbai, not to mention most of the country, to a standstill. People in their homes watched the news while events played out outside. All along the streets, people were sitting on the roads and the footpaths. Men in white tunics and pyjamas or shirts and trousers stood or sat amongst the crowd. Some men were in dhotis and sported bright turbans or white topis. The women were in saris, their pallus covering their heads or only the shoulders. Many women in salwar kameez. There were children too, girls in frocks and boys in oversized, soiled T-shirts and shorts, some sitting, many of them standing.

So it had happened. People from rural India had marched into the cities, claiming their rightful place in the nation’s prosperity. They wanted a share—a fair share in the better life that their urban countrymen had been enjoying every day of their lives. As the news spread during the course of the day, it became clear that others too had joined the farmers in their protest rally. Other people from the village community, cowherds and shepherds, weavers and blacksmiths, potters and cobblers, had all lent their support, standing firm alongside the farmers. The city folk were not far behind. Slumdwellers showed solidarity too. They only had to walk out of their homes and occupy the streets and maidans situated close to the slums. They entered building compounds and filled up the empty spaces they found. It was a peaceful protest. But as the sheer number of people blocking up the streets and empty grounds rose, fears and rumours of potential violence spread.

How did this come about? Why now? What triggered it?

In a year when the country was facing drought, a group of farmers in Maharashtra, who could not remember when they had had their last good meal, were closely watching the news in the only village home that had a television. They were tired not from working in the fields but from waiting for the rains. They were aware that at this late juncture, even if it rained, the crop yield would only be a fraction of what they’d hoped for, or none at all. Four farmers from the village had killed themselves in the last few weeks. The others watched the television with eyes as dry and parched as the land, feeling as powerless as the emaciated children on the screen. Silently they watched their own story being told to them by a man in a suit and tie. A woman broke into quiet sobs. But soon there was a commercial break, with advertisements for shampoo, cars and pizza oozing with cheese. This was followed by the next big news item—a daughter of a government minister, the groom the son of an industrialist with a business empire in petrochemicals, infrastructure and mining. The opulence of the wedding was on full display. The woman who had been sobbing quietly stood up. She picked up a small earthen pot nearby and hurled it at the television screen. Others in the room stood up and watched her in silence as someone switched off the television. They all returned to their own houses, but no one slept that night.

In the morning, one of the men from the village, who happened to be a part of Vikram’s network, told him it was time to act on their plan. Vikram spread the word and sent the messages to the set of contacts who were the principal nodes in his database. They in turn sent messages to people in their own list and so on, until all the people in villages, towns and cities received the message. They also informed the police and permission was sought for a peaceful march and assembly in the Azad maidan in Mumbai, and several parks and maidans in all the towns and cities across the country. Nobody had envisaged the scale of the march. Nobody had expected that everything would come to a complete halt.

Within six days, the villagers started to walk or take bus rides to the nearest railway station and board trains to Mumbai. Word got around to other villages, districts, and across states. It is time, six days from now. That was the message. They had often talked about doing this and had been eagerly anticipating it. All over the country, the poor left their villages and started moving towards the cities, to all the state capitals. Vikram informed Trevor and Mallika, his principal contacts in Mumbai that they will be at the Azad maidan. Trevor and Mallika contacted many others within the city who had joined the network, many of whom were students, social workers and young professionals. Trevor also contacted people who formed a hidden majority of the network—the men and women who lived in Mumbai’s innumerable slums and shanties. People who earned their living as workers in small factories, mills, meat shops, metal works, car repair, those selling goods in small matchbox-sized shops, domestic helps, nurses, autorickshaw and taxi drivers.

And that is how Mumbai stopped as the trains, buses, and every available space on the roads were occupied by people.