The photograph of the 62-year-old Sakhu Bai’s foot from the Kisan Long March in Mumbai earlier this year spoke more than thousand words about the plight of the female farmers across the country, struggling to be identified as owners of their land. On November 30, 2018, thousands of female farmers like Sakhu Bai walked the streets of Delhi, from Ram Leela Maidan to the Parliament street – some with blistered feet, some with wounds from the violence in their fields, but all with the commitment to make their stories heard, as their stories, by the virtue of their realities, are intertwined with the destinies of their men.

Parvati Kumari Devi, a middle-aged farmer from Zila Madhubani, said, “I wake up every morning, and work in the field tirelessly every single day, as I manage the household chores as well.” When asked about her right to own the land, she said, “The saree I am wearing right now is given to me by my family. The men decide what clothes I wear; do you think I will be able to have anything in my name?”

Although a large number of rural women are engaged in agricultural work, mostly as agricultural labourers and marginal workers, as many as 87 per cent of these women do not own the land they work on, as per an Oxfam report released in 2013. This is primarily because of the patriarchal mindset prevalent in the society, which has kept women bereft of land ownership for generations.

Another glaring example of the discrimination against women in rural areas is the wide gap in wages. As a recent ILO report on wages pointed out, India has one of the largest wage gaps in the world – of about 34 per cent – between women and men. This is the ground reality in spite of laws explicitly prohibiting difference in wages for same nature of work.

Thus, the deep-rooted gender discrimination inherent within agriculture does not help women stake claim to their right to own the land they cultivate. This conflict assumes greater importance post the death of their husbands who are recognised as the main stakeholders of the land.

Despite changes in the inheritance laws, independent evaluations have time and again shown that cultural barriers have impeded women from inheriting land. The picture looks even grimmer in agriculture, owing to rural poverty, lack of basic education, and the stigma of being a widow in a land where marriage is sacrosanct.

Usha Devi, who travelled to Delhi from Bhadohi District of Uttar Pradesh, shows her wounds and says, “I have come so far. My husband is no more, I am being forced to work as a labourer on someone else’s land where I am often beaten up and hurled abuses as.”

The title of a farmer is an important one, as it will decide whether a farmer’s family gets compensation or not. This definition includes the fate of irrigation facilities in the farm, the productivity of the crops, the requirements of the children and of the elderly.

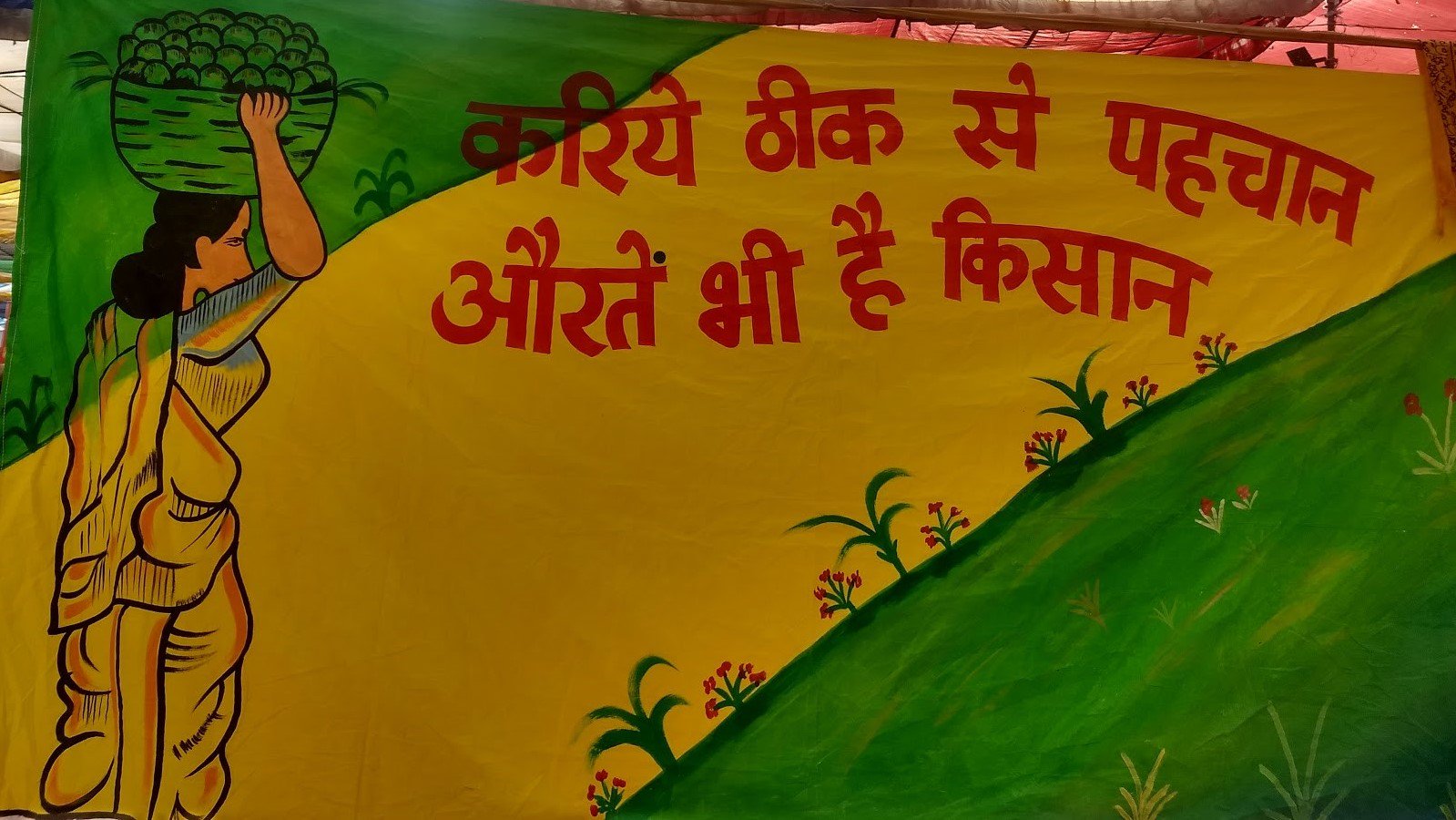

Women are never recognised as farmers, but only as cultivators, as they farm alongside their husbands. However, they continue to do so even after their husbands pass away. Existing policies only recognise these women as farm labourers, making it extremely difficult for women to avail the title of a ‘farmer’ after the death of their husbands. As a result, most women in agriculture cannot avail of government schemes meant for farmers. They cannot access institutional credit for farming, or get subsidies. Without any security net and with limited access to government schemes, women are driven deeper into the circle of debt and penury.

The lakhs of farmers who marched in the Kisan Long March in New Delhi on November 29-30, have demanded a 21-day special session of Parliament to discuss the agrarian crisis. A bill called Women Farmers’ Entitlement Bill, 2011 was presented in Parliament in May 2012. Due to the lack of political will, the private member’s bill introduced by agricultural scientist MS Swaminathan himself, had lapsed in the parliament, but the farmers have now demanded reintroduction of this Bill in the Parliament.

Explaining the significance of this Bill, senior journalist P. Sainath told Newsclick, “Women farmers are denied property rights, they are denied ownership of land. Barely eight per cent of the women in this country hold land in their own deeds. You cannot solve the agrarian crisis if you do not engage with the rights and entitlements of women farmers. Women farmers and women farm labourers do a bulk of work in agriculture in this country. You cannot evade the issues of the section that is working the most in agriculture, and hope to solve your crisis.”