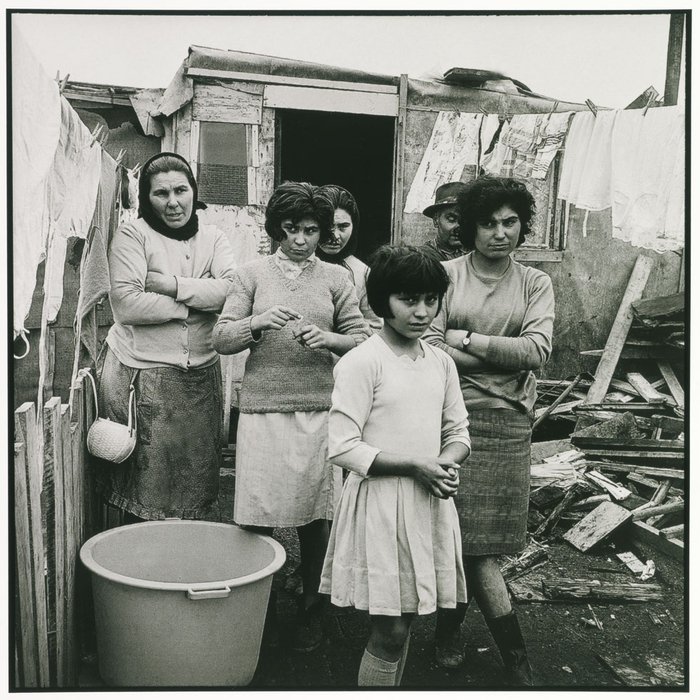

Gérald Bloncourt (1926-2018), who died last week at 91, had a close sympathy for political exiles. In 1965, Bloncourt went into the border region between France and Spain in the Pyrenees mountains to greet and photograph Portuguese refugees who fled the dictatorship of Antonio Salazar’s Estado Novo. He followed them into their shack towns that would eventually ring Paris, from Champigny sur Mame to Aubervilliers. Many were political refugees, people who had fled the periodic crackdowns against the working-class movements and the left. In 1964, the Portuguese dictatorship attacked unionists and the Left on the pretext that a Lieutenant General – Humberto Delgado – was plotting a coup with the Portuguese Communist Party. It was politics that sent people to brave the crossing into France. It was politics that took Bloncourt to greet them with his camera. It was this thick gaze, these faces looking defiantly at the camera that told you about their politics. We are not merely refugees, they are saying; we are militants for a better world.

As a young university student in his native Haiti, Bloncourt helped start a paper – La Ruche (The Beehive). Drawn to Marxism like his fellow radicals, Bloncourt’s paper published an editorial on 1 January 1946 that called for democracy over the ‘fascist oppression’ of the post-war government of Élie Lescot. Two days later, some of the editors were arrested. Bloncourt met with Stephen Alexis, then a young medical student but later a novelist (Compère Général Soleil, 1955) and a communist militant, and other student leaders. They began a series of cascading protests that drew in organisations of workers and feminists. Bloncourt had joined the Communist Party, which participated in these protests against the US-backed dictatorship. A year into the protests, in February 1946, Bloncourt was picked up by the para-military forces, put on an airplane bound for the Dominican Republic and sent into exile in France.

When he encountered the Portuguese exiles, he saw himself in them.

In Paris, Bloncourt worked for the Communist Party newspaper L’Humanité. It was this connection that drew Bloncourt to visit the USSR several times in the 1960s, when he spent his days photographing ordinary people doing ordinary things inside the Soviet Union. Thirty years before Bloncourt visited the USSR, the Soviet artist Valentina Kulagina wrote about Communism and photography. In 1931, Kulagina noted, ‘We are for a revolutionary photography, materialist, socially grounded and technically well equipped, one that sets itself the aim of promulgating and agitating for a socialist way of life and a Communist culture. We are against flag-waving patriotism in the form of spewing smokestacks and identical workers with hammer and sickles. We are against picturesque photography and pathos of an old, bourgeois type’. Instead, Kulagina championed the use of photo-montage, putting pictures and other forms of art into conversation with each other, cutting up fragments of pictures and using them to elicit strong reactions from the viewers.

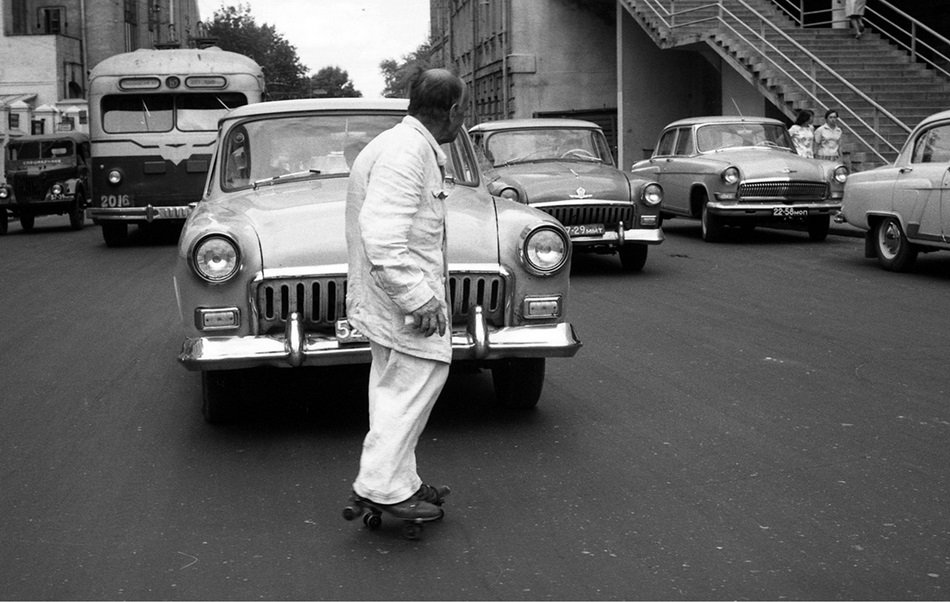

Bloncourt’s approach was different. He was interested in the world of ordinary people doing extraordinary things, an elderly man in Moscow in 1963 – for instance – roller staking across a busy road.

Soviet life was not only about protest and work. It was also about being alive, doing silly things. This is what Bloncourt was keen to demonstrate. There are pictures of young people in a Moscow park, women farmers dragging a child in a sled, textile mill workers discussing a new weaving pattern, children in school, a jazz band, men and women at an outdoor table playing dominoes, a man and a woman inside a phone booth making a call. The world of the USSR comes alive in these pictures (as they do in those of the German photographer of this period, Hans-Rudolph Uthoff). There is a picture of some men leaning over a chess match. You can’t see the board. There is a poster of Lenin above them. One man is glancing back towards Bloncourt, almost asking him to come closer. This is their life. He might want the photographer to have a better look of the board.

The purpose of the communist photographer, Kulagina and Bloncourt show us, is not only to take pictures of demonstrations and marches. The point is to make photographs that when seen by the workers and the peasants allow them to think about the contradictions of capitalism and then to inspire them to action.

In 1979, Bloncourt left Paris for the industrial town of Longwy that sits on the France-Belgian-Luxemburg border. Across Europe, workers went on strike that year against a new global order that was prepared to abandon industrial production inside Europe for lower wages elsewhere in the world. This was not a view based on paranoia. A few years before, the heads of the main industrial states met in Rambouillet (France) to form the G7. At that meeting, West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt said,

I am a close friend of the chairman of the textile workers union in Germany. It is a union of shrinking industry. I would hope that this would not be repeated outside this room. Given the high level of wages in Europe, I cannot help but believe that in the long run textile industries here will have to vanish…. It is a pity because it is viable… but wages in East Asia are very low compared with ours.

This is precisely what the French industrial barons and the French government had decided for towns such as Longwy. Violent confrontations broke out in January. The tension ran down the length of 1979, as British workers entered the period known as the Winter of Discontent and as West German workers in the steel union (IG Metall) went on strike for the first time in fifty years. The workers knew that they were being abandoned by the State, which had thrown its chips openly with the barons of capital. No more mediated compromise, no more space for bargaining. The militancy of the workers at Longwy showed that they were not going to be fooled by the political class. They were going to fight back.

Bloncourt’s photographs from that strike wave capture the confidence of the workers. The picture above shows the diversity of the working-class in that north-eastern town of France. Two North African workers, with signs in Arabic and French, chat with their fellow workers in anticipation of a march. They are smiling. There is comradeship here.

Longwy’s struggles ended with the closure of the factories. In 1962, this small town had jobs for 30,000 steel workers. By 1982, there were only 6,700 such jobs. Workers from the town went to Paris, entered the office of the head of the nationalized steel company and dragged his furniture onto the streets. Their militancy was unabated. A few years later, even these disappeared. Shops closed, those that remained had little in their windows. The Auto School of the Future closed down.

The workers ran for office under the standard of the Communist Party. One became the mayor. It was known as Red Longwy. It is now forgotten, although its people have not forgotten their proud strikes captured in Bloncourt’s photographs. Despite its poverty, this region of France does not vote for the neo-fascists. There is no room for them. Perhaps the solidarity between the workers from different parts of the world has a legacy that remains.

Two years ago, the journalists Éric Amiens and Fabian Charles went to see Bloncourt. They asked him about his politics. He talked about how he took to Marxism and Communism through his cousin, who learned it from the Haitian writer Jacques Romain. ‘I am communist’, he said. The suffocation of neoliberalism troubled Bloncourt. Marx’s ideas are needed, he said, ‘to build a different society’. Bloncourt died last week.