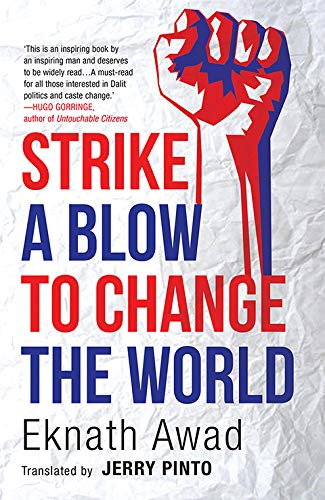

Strike a Blow to Change the World is an autobiography of the prominent Dalit activist Eknath Awad. The book was recently translated into English by Jerry Pinto. In his book, Awad describes his rage against the humiliation of the Mangs by the upper castes; his struggle to overcome caste prejudices as well as extreme poverty to get an education; his days of activism; joining the Dalit Panthers; his decision to return to Marathwada and much more. The following is an excerpt from the book, as well as a conversation between Eknath Awad’s son Milind Awad and writer Githa Hariharan.

I was born to Mang parents and so I got stuck with their caste. Some people are proud of their caste status. I was not one of them. I had all but abandoned my caste; ‘all but’ means it still existed on paper. But it was because of this paper that I got a scholarship from the college. Beyond that, I had no pride in my caste.

On the contrary, in the movement, young men from different castes would get together to discuss ways to break the caste system. This process had two parts. We young men would come together and talk about the specificities of our caste situation and bond over the pain we had endured. There, I represented the Mangs in an attempt to forge some unity among us. On the other hand, I wanted to wash away the vestiges of caste from my behaviour, from my life. My relations had cast me out already. Now I wanted to remove the marks of caste from my home as well. My father bore the marks of his low caste on his head in the form of the clump of hair. The clump of hair a Potraj wore was supposed to signify the ornaments of Mari-Aai. When my father begged for a living as a Potraj, he would often be called to a village. This was because Mari-Aai would possess him. When the goddess descended into him, he would begin to spin. His face would be smeared with turmeric and koonkoo and shendur. Whoever had a question would put a lime into Baba’s hands. He would rip this with his teeth, shouting Ha-ha-haa. Then a baby chicken would be put into his hands. Baba would take that live chicken’s head between his teeth and with a single jerk of his head, he would decapitate it. A fountain of blood would spurt from it. Baba’s mouth would fill with blood. I wanted him to stop doing all this. I wanted to rid our home of this Potraj business once and for all.

Once, I was home for the holidays. I had to get some money together and go back to college. That was how it was with me in those days. One day, Gaya and I had woven some ropes. We had to take them to the bazaar at Kuppa to sell them. When I got to the market, a crowd would gather around me, for they recognized me as an activist and a worker in the movement. That meant I could not sit in the market to sell the ropes. Baba and Gaya would sit to sell the ropes. Once they were sold, we would return home with the money. That was how we spent those days. I sent Gaya ahead and told her to cook some meat.

Baba was walking in front of me in the market. From where I was, I could see his clump of hair. It began to bother me. I said: ‘Baba, cut your hair.’ Baba was startled. ‘What now?’ he asked. I knew that he was not going to agree easily to cut this hair, which he had maintained for so many years as a sign of Mari-Aai’s blessings. So I said again. ‘Baba, we are managing somehow with the work that we do. You don’t even go to beg any more. Then why keep your hair like that?’

Baba stopped to stare at me. When I was in the fifth standard, I had thrown a tantrum demanding that Baba get me a compass box. Then, Baba had taken a loan of ten rupees. Each week he had agreed to pay a rupee in interest and only then could my poor father buy me a compass box. Now I was throwing another tantrum. And Baba was looking at me in the same way.

Baba had a ready tongue with abuse. He would curse me, both in anger and out of love. Baba took his hair in his hand and said, ‘Cut my hair? Go on then, motherfucker, you cut it.’ Since he had agreed I took him immediately to Eknath Warik, a barber who sat with his implements in the bazaar. People would sit with their heads bowed in front of him. When he was shaving you, he would rub the foam off the edge of the blade on to the base of his thumb. That meant his hands were always flecked with hair and foam. I sat Baba down in front of Eknath and said, ‘Cut off that clump.’ He was stunned. He said, ‘Aarra, his hair is Mari-Aai’s tree. This you want me to cut? Nothing will happen to you but the sin will be mine.’ I said, ‘Aaho, I’ll cut the clumps of hair. Will you do the roots? If anything happens, I take it upon myself. I promise nothing will happen to you.’

Warik agreed. Baba sat down. I took one strand of his hair in my hand and shouted, ‘Hey Mai Mari Aai, if anyone is to shit or to vomit, let it be me. If I am cutting a tree that belongs to you, then let the punishment be mine.’

And so saying, I plied the scissors. Warik took care of the rest of the hair. Baba’s head was shaved bald. For all his life he had walked around with the weight of that hair. Perhaps he felt lighter now. One of my aunts, Lakshmibai, had come to the market that day. I sent her and Baba ahead. I was walking behind them. I had to prepare mentally for what was coming.

As I expected, Lakshmibai was enlightening Baba about what had just happened. On the way, there was a farm by the name of Savaashi. That was where I heard what she was saying, ‘What have you done, cutting down the trees of Mari-Aai that grew on your head. You have spawned a devil.’ Listening to Lakshmibai brought Mari-Aai down into Baba’s body. He began to tremble and shake even as he walked along. I set them on the road to home and went to my cousin Hari’s liquor still. I got a good bottle of pehli dhaar, the first distillation. When I got home, Baba was still spinning. I took a cup with a broken handle, filled it with alcohol and said to Baba: ‘Come on, Mari-Aai, come on. This is the first distillation.’ Baba scoffed it in a single gulp. I filled the cup a second time. By this time Mari-Aai seemed to be missing in action. Baba put the cup to his lips a second time. He said, ‘What possession! These beliefs ruined my life. Mari-Aai even broke my teeth. For the sake of my stomach, I would dance for her, but the cursed one never gave me one good day in return.’ Baba smiled. His front teeth were missing. Killing all those baby chickens had ruined his teeth. That night Baba abused Mari-Aai to his heart’s content. In the devhaarya, the shrine at home, we had some tin images. He said: ‘Throw that stuff out of the house.’ That was what I wanted. I wrapped the images in a cloth and put them into the river. The last remnants of Baba’s Potraj days floated away. Every sign of being a Mang had been erased from the house.

[…]

I had a good position in CASA. But soon T.K. Abraham moved out of being Chief Officer of the Mumbai office. Shalwin took over his place. Shalwin was a religious man. He was always quoting Christ. I had nothing against Christianity or Christ but I was also a committed Ambedkarite. I did not bring Christ into my camps and trainings. But if I excluded Christianity, it was because I excluded all other religions and gods as well. Despite this, I had some standing in CASA. Perhaps Shalwin was also envious of me. He began to oppose me. As my senior, he kept demanding that I submit reports. I began to have fights with him and at the same time, I had an argument with a colleague called Deshmukh.

Every month all the workers came to the office to share their experiences with each other. Each one would talk about the status of work in his district, the programmes that were planned for the coming month and such matters. We would analyze each other’s styles of functioning and seek to learn from our mistakes. At one such meeting, I brought up something I had against Deshmukh’s style of operation. Deshmukh was a Maratha from Beed. When I went with him to his village, I saw the Dalits bowing their heads in front of him. I described this at the meeting. ‘A social worker should take no pride in caste. If the Dalits in his village bow before him, Deshmukh should himself offer them pride of place and seat them nextto him. But he has not been able to deal with his pride in these matters.’ Deshmukh was deeply offended. He replied, ‘It is Eknath who is the casteist. He sees caste everywhere.’

I said, ‘If by speaking out against your caste consciousness, I am labelled casteist, I accept the accusation.’ At the end of the discussion, Deshmukh had tears in his eyes but I did not withdraw my words.

It was not as if I reserved my accusations of casteism for the upper castes alone; I also examined carefully the actions of my own caste brothers. BAMCEF,* a socialist organization, had organized a meeting of the Matangs in Aurangabad. I went there as an observer. A Mang professor mounted an attack there on the Mahar community. ‘It is the Mahar who is responsible for the backwardness of the Mang community. The Mahars get all the benefits and there is nothing left over for the Mang. If Dr Ambedkar is a Mahar leader, we should take Annabhau Sathe as our leader. Lahuji Vastad Salve can be a symbol of our pride and we can progress…’ and so on. After he had spoken, I spoke too and without restraint. ‘You are dividing us up on caste lines. Should an educated person from our communities offer correct direction to the people or should he be leading them astray? Dr Ambedkar is the leader of us all. If anyone seeks to put Babasaheb into a caste box, such a person should be greeted with slippers.’ This was greeted with a hearty round of applause. The BAMCEF people came to meet me. The next time, they asked me to preside over a session too.

*The All India Backward (SC, ST, OBC) And Minority Communities Employees Federation, known as BAMCEF, is an organization of employees from Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes and Minority Communities in India.

[…]

I have seen countless instances of injustice, witnessed atrocities without number. How many can I count? How many can I tell you about?

A Dalit boy tucks his shirt into his trousers, sets a pair of goggles on his nose? The defenders of caste who have nothing better to do will tear his shirt and smash his dark glasses underfoot. Then they will ask him, ‘Will you pluck out our pubes, dheda?’

Is his crime a letter from a high-caste girl found on his person? They will tie him to a pole in the village square and beat the life out of him.

Did you look at one of our girls? Did you wink at her? They scoop his eyes out with a knife.

Does a Dalit want a holiday to celebrate Ambedkar Jayanti? His master ties his feet with a rope and dangles him over a water-tank and swings him around. Now will you ask for time off to celebrate Ambedkar Jayanti?

Does a Dalit dare to buy land that abuts an upper-caste farmer’s property? How dare he? Will yesterday’s labourer walk around as today’s farmer? Here, take that, Mangtya. And they take a scythe to his skull.

A Dalit girl goes to college… Look at those goodies! Come with me into the sugarcane fields! What can the girl do? Who can she tell? Her poverty-stricken father will say: ‘Give up your education.’ The girl kills herself. And the boy walks free even if accused of a caste atrocity.

The police refuse to register cases. The government does not set up special courts. The judge asks a witness, ‘You’re an old man. In the dark of the night, how can you be sure that it was this man and he alone who attacked you?’

The aged witness: ‘Sahib, this is a boy from the village. I know his whole family.’

The judge’s epilogue: ‘Your vision is weak so the accused is absolved and may go free.’

It was in such a setting that we took our positions at Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan. The activists began to write songs:

Shaan se jiyo, shaan mein, Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan mein…

Utar jaan maidaan mein, Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan mein…

Bhai tu kis soch mein pada

Nahin koi chhota-bada.

Baat rakho dhyaan mein, Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan mein…

Live with dignity, with Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan

Come fight the good fight, for what is right with Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan

What stops you, brother?

No man is bigger than any other!

Bear this in mind, in Maanavi Haq Abhiyaan.