Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar is a well-known name in contemporary Indian literature. His debut novel, The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey, won, among many others, the 2015 Yuva Puraskar, and was longlisted for the 2016 International Dublin Literary Award. His second collection of stories, The Adivasi Will Not Dance: Stories, opened up to wide acclaim and was shortlisted for the 2016 Hindu Literary Prize. Largely recognised as one of the pioneering full-length Santhal works in English, his works reflect a Jharkhand-based ethos.

This year, he published Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire: Adventures in Champakbagh, his first book for children. It is the story of Mohan Chandar and his family who by inviting an unidentifiable creature into their home, on a dark stormy night, set into motion a series of adventures that changes their lives forever. Kanika Katyal, a member of the Editorial Collective of the Indian Cultural Forum interviewed Shekhar about the book, his inspiration behind it, if children’s literature should be seen as a case in sociological practice and more.

First and foremost, I wanted to know about the conception of the book. For a book so deeply rooted in the ethos of Jharkhand, one would imagine that a host of Indian folklore went into the making of Jwala Kumar, but curiously enough, when talking about the inspirations to his book, Hansda, reveals, “George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones – especially its HBO adaptation” – (although not distinctly categorised as children’s literature), was for him “a bigger inspiration than any children’s literature!” Even, the immensely popular magazine, Champak, came in “only, when I was looking for a name for the village”, he says.

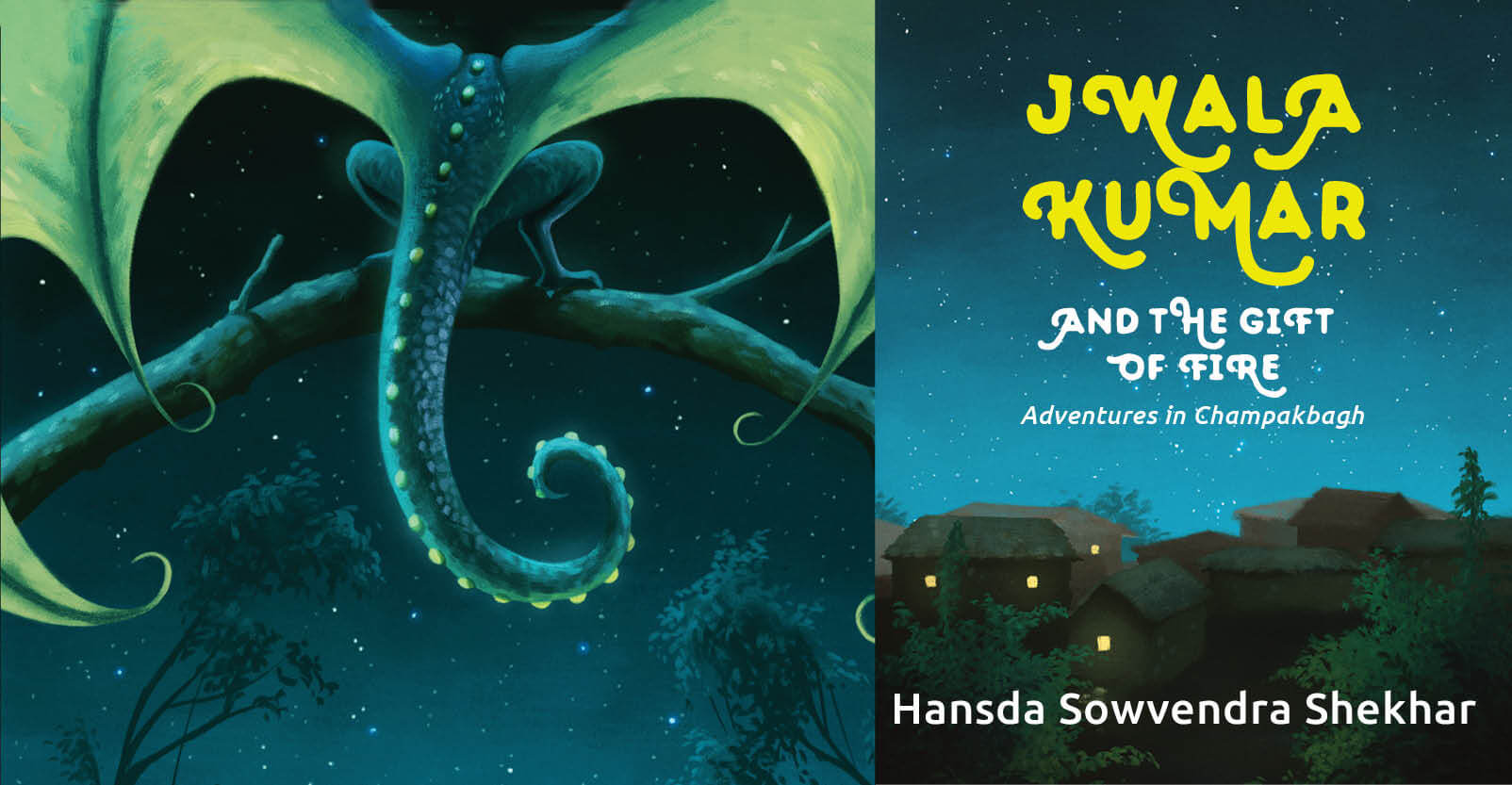

Each chapter of the book is laced with engrossing illustrations, designed by 21-year-old illustrator, Krishna Bala Shenoi. Given the important role that illustrations play in a children’s book, collaborating with a fellow artist on one’s project can both be a boon or a curse, especially if they hail from a different discipline. However, Sowvendra Shekhar seems to have had a synergetic experience working with Krishna Bala Shenoi. He affirms, “I am very happy with the illustrations that Krishna Bala Shenoi has done for Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire. Krishna Bala Shenoi is a very gifted artist and I did not have to give him too many pointers. He understood what I wanted in the illustrations.” In a sense, a collaborative, formalistic project at the seams also alludes to the larger possibility of collective building that children’s literature as a genre aims to promote.

In the story, the family that takes Jwala into shelter, is one that belongs to a backward socio-economic background, therefore, I was intrigued about the ambiguous “Kumar” last name given to the creature, and asked the writer to explain that choice.

“I come from Jharkhand, a place that was once a part of Bihar. Kumar is a common last name here. Please take note: I said last name, not surname. In my part of the world, one’s surname is often a marker of their caste, community, etc. So, people often have Kumar (for males) and Kumari (for females) as their last names if they do not wish to reveal their caste, community, etc. In Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire, I was not dealing with the caste of the human characters. So, I decided to give Mohan Chander a neutral last name – Chander – and, similarly, I chose to use Kumar as Jwala Kumar’s last name,” replied Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar.

Though Hansda’s work is deeply political, he remains an artist who expresses great discomfort and reservations about conventional labels and demands a different kind of engagement through his work. In the story, Jwala Kumar is an “outsider”, who repays not only his immediate hosts but the entire village with eternal warmth and hope. By creating this “friendly stranger”, I asked him if he aimed to comment on the larger global climate of hostility towards “outsiders”. He told me that although he did not intend the book to be that, yet, if the story of Jwala Kumar was seen as a comment on current issues, he was happy with it, “but I had not intended to make any comment”, he clarified

Finally, I asked him if the ban on his last book, The Adivasi Will Not Dance, influenced his decision to take recourse to a genre like children’s literature. “The Adivasi Will Not Dance had nothing to do with my writing a children’s book. Game of Thrones Season 1 and an untimely rainfall in my hometown Ghatsila had more to do with Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire,” reassures Hansda.

Image Courtesy: Speaking Tiger Books

Image Courtesy: Speaking Tiger Books

Once upon a time, on a dark, stormy night, Mohan Chandar found a creature crouched under a periwinkle bush in their backyard and brought into his home. Little did he know that by opening his doors to a/this strange creature, he was inviting a whirlpool of adventure into his life, and the life of his family.

Neither bat nor lizard, but like a close-cousin of the chameleon, the creature astonishes the family. It was nothing like they had seen before What sort of animal is this? Is he friendly? What does it eat? Where will it sleep? The family is astonished. Yet, it was the kind small on the creature’s face as he lay sleeping in a corner that told the family it was special. He is soon accepted as one of them. He even makes friends with the birds of the village!

The children identify him as a boy and call him Jwala Kumar. Slowly as Jwala Kumar reveals his special powers, a trail of exciting everyday adventures unfolds of the family as they engage in a game of hide-and-seek with the village, to keep his existence a secret. In this way, despite a generous, and large-hearted family at the centre, the story hints towards the looming fear of hostility against outsiders in the village, and in a larger sense, the world.

Amidst, rain and thunder and bad crops and roads, Hansda paints a vivid ethos of a wetted village in Jharkhand. Incorporating elements of folk, and fantasy and fairytale, he spins a tale of what Anjana Basu calls “practical magic”; as, ultimately, Jwala Kumar, an “outsider”, goes on to repay not only his immediate hosts but the entire village with eternal warmth and hope.

The given extract is an example of such a hide-and-seek episode from the book, where Jwala Kumar’s stunts pose trouble both for himself and the family. The book is replete with such episodes that form the fabric of a children’s tale and is bound to make a joyful read for both young and older adults.

Following is an extract from Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s book, Jwala Kumar and the Gift of Fire: Adventures in Champakbagh released in 2018. These extracts are from the chapter titled ‘Flight, Food, Fuel, Friends’.

In the faint moonlight, Jwala Kumar looked like something out of stories, out of dreams. A huge bird that was not a bird. A creature that the village of Champakbagh would never be able to identify, never be able to know.

What had he brought to his house? What had he sheltered? What was he looking after? Mohan Chandar thought all this and felt strange. He felt doubtful. He felt special. Watching Jwala Kumar make circles in the night sky, his wings spread wide, his tail held straight behind him, as he flew, made Mohan Chandar feel happy and apprehensive at the same time. Happy, for what he had done. Apprehensive, for what might come. Yet, at one point some minutes later, the feeling of happiness and excitement overcame the feeling of apprehension. It was a feeling he could not describe.

And good sense struck him just that moment.

‘Children,’ he said to Naren, Biren and Namita, ‘come, come inside the house.’

‘Baba, wait,’ Namita said, her eyes fixed in the sky.

‘Listen, Naren’s mother,’ Mohan Chandar said to Rupa Devi, ‘come, come inside,’ Naren’s mother, now you don’t turn into a kid with the kids. Try to understand. Come inside.’

‘Wait,’ Rupa Devi, too, like her daughter, refused to listen. ‘Where did he go now? Have we lost him? Out Jwala is flying in the sky!’

‘Stop. Hush. Lower your voice.’

Mohan Chandar was wary. What if their neighbours saw them staring at the sky at night?’

‘Naren’s mother,’ Mohan Chandar called out to his wife again. ‘We need to go inside the house. If people see us looking at the sky like this, they might suspect things. They might come to know about Jwala Kumar. We might lose Jwala Kumar. Why don’t you understand? We have to keep Jwala Kumar safe.’

Rupa turned around to look at her husband. Yes, he was right. What if people come to know of Jwala Kumar?

‘Naren, Biren, Namita, enough,’ she called the children. ‘Come inside now, come inside. It will not be safe for Jwala Kumar if we keep on staring at him.’

‘But, Ma,’ Biren said, ‘I want to see Jwala Kumar flying.’

‘See him from inside the house,’ Rupa Devi pushed her children inside. ‘He is not going anywhere.’

‘And what if he loses his way?’ Namita asked. ‘What if Jwala Kumar is not able to return?’

Just then, WHOOOOOSH… Jwala Kumar glided right into the house and landed smoothly on the mud floor. He looked happily at the family.

After that, every night, soon after the night meal, became Jwala Kumar’s outing time. He flew up in the sky, though not far from Champakbagh. The children loved to see him fly, but they watched cautiously so that others did not see them seeing him.

One night, Jwala Kumar did cartwheels mid-flight. Out of excitement, Namita clapped. One elderly man passing-by asked the children, ’What happened? Why is the little girl clapping her hands? Did she see something? Now, at night!

The children were speechless.

‘Urm–Kaka,’ Naren said, ‘Actually–our sister is learning to count the stars.’

‘Yes,’ Biren added immediately, ‘and she counted all the stars in the sky tonight so she is clapping.’

‘Ohho! I see,’ The elder man walked away laughing.

As soon as the man left and the coast was clear, Jwala Kumar whooshed right into the house and landed on the floor, watching the children happily.

There really was something special about Jwala Kumar.

Read More:

Suspension on Writer Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar Revoked

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar: “I don’t like being labelled as an adivasi writer”