On 6 September, Nayantara Sahgal was conferred the 2nd Lal Ded Award by Sarhad, a non-governmental organisation based in Pune.

Sahgal walked up to the dais with her usual poise and delivered her acceptance speech. This is not an ordinary award, she announced, firm but equanimous, and continued: “It is named after a woman who is inseparable from Kashmiri culture and who represents the very beginning of Kashmiri literature.”

Lal Ded, who lived and composed her verses in the 14th century, is not merely a historical figure in 21st century India. Sahgal immediately made this point by invoking the status of women in our culture. It is difficult to be a woman in our culture, she said, and narrated the difficulty Lal Ded faced when she wanted to live the life of a wandering nun. This was a choice only available to male ascetics in the 14th century: “This little village girl, Lalleshwari, was given away in marriage, according to custom, at the tender age of twelve.”

“She then led a life of terrible suffering. She was starved and ill-treated by her cruel mother-in-law and abused by her husband. But she was born with a craving for the divine and nothing could deter her from her intense spiritual longing for union with the divine. She finally broke away from her cruel in-laws at the age of twenty to go to a Shaivite saint and be accepted as his disciple. And after completing her discipleship she became a wandering nun. No woman had done this before. Seeking the divine in this fashion was a male prerogative. She was attacked, insulted and cursed and her verses describe the torment she went through. This young woman was alone in this frightening and hostile atmosphere and yet nothing could stop her.”

In one of her vaks, oral utterances in culture, translated into English by Ranjit Hoskote, Lal Ded narrates her ordeal with an image: wrestling with a lion.

What the books taught me, I’ve practised.

What they didn’t teach me, I’ve taught myself.

I’ve gone into the forest and wrestled with the lion.

I didn’t get this far by teaching one thing and doing another.

It is hard to not compare the parallels between Lal Ded’s hardships and Sahgal’s life lived in dissent. Born into the Nehru family – Jawaharlal Nehru was her uncle – she spoke up against her cousin Indira Gandhi after she imposed the Emergency. Three decades after that event, she returned her Sahitya Akademi award protesting Akhlaq’s lynching in Uttar Pradesh. The Lal Ded Award ceremony happened in the wake of the arrests of activists, journalists and lawyers, allegedly linked to the violence in Bhima Koregaon. The Pune police had made the accusation, which has recently been dismissed in a dissenting judgement by Justice Chandrachud. Sudha Bharadwaj, one of the five arrested, is a lawyer and General Secretary of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), a human rights organisation formed in 1976 under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan, one of the most vocal leaders against the Emergency. Sahgal was the Vice President of PUCL in 1984.

When I met Sahgal at India International Centre the next day, I asked her if the situation now is similar to the Emergency. She cut me short, almost in a manner that highlights the urgency of the situation, and resolutely said, “It’s worse.” “It’s very frightening, it’s very dangerous. It’s worse because the Emergency was a declared disposition. It was there, there was no confusion about it. This government calls itself democratic but behaves like a dictatorship. That’s dangerous.”

She quickly mentioned the arrests purportedly in connection to the violence at Bhima Koregaon, for which the Pune police appointed a ten-member fact-finding committee and has linked it to two Pune-based Hindutva leaders—Milind Ekbote and Manohar Bhide. “They are arresting these human rights activists. What about the organisation that is manufacturing bombs? See, what answer do they have for that? They don’t have an answer. It’s a very frightening situation. Much worse than the Emergency. Because you knew it was a dictatorship. You expected nothing else. You didn’t expect to be in this situation by a change of government.”

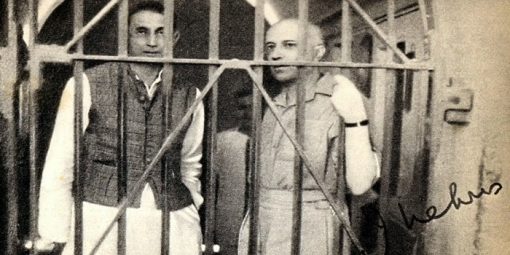

Even in times of incarceration, people find a refuge in literature. Sahgal’s father, Ranjit Sitaram Pandit, translated the 12th century Kashmiri historian, Kalhana’s chronicle, Rajatarangini, from the Sanskrit to English, over two jail terms during the anti-colonial struggle for independence from the British rule. Sahgal’s eyes sparkle when she talks about her father.

“My father died during his fourth imprisonment. He had two passions: Kashmir and Sanskrit. He found these two passions combined in the 12th century history of Kashmir by Kalhana. So, he took it on to translate it into English, which he might have done anyway, but he did it specially so that my grandfather — Motilal Nehru — might be able to read it. The Nehrus had grown up with Persian; my grandfather [Motilal Nehru] knew Persian before he knew English. He didn’t know Sanskrit. So my father translated it into English. He was very close to his in-laws and shifted from Maharashtra to Uttar Pradesh to live there and they combined forces to join the national movement. My grandfather did not live to see the translation published. My father, my uncle [Jawaharlal Nehru] – all of them were going to jail while they were working for the Congress, as I said, he did some of the translations over two jail terms. So, when it finally came out my grandfather was dead.”

“So, my uncle, Jawaharlal wrote the introduction, and what he wrote shows how much in awe he was of my father’s scholarship and what a lot he learnt. He couldn’t go through the Rajatarangini from the first page to the last, but what he read of it, he was filled with admiration for my father’s learning. And, above all, it is lavishly footnoted telling the story of the time. It’s an amazing book. So that was my father.”

At the felicitation ceremony organised by Sarhad, a translation of Rajatarangini by Aruna Dhere and Prashant Talnikar into Marathi was also released. Sahgal was very happy with this, especially because Marathi is her father’s mother tongue. “I am happy that it has now been translated into his mother tongue, Marathi, by the scholars Dr Aruna Dhere and Shri Prashant Talnikar. I would like to thank them, and I offer my grateful thanks to Shri Sanjay Nahar and Shri Sanjiv Khadke for making this classic available now to Marathi readers,” were her concluding remarks the night before.

In times of Emergency, is it possible to remember that language initiates a civilising process. Lal Ded’s sayings were popular among the people of Kashmir and have been transmitted through them. In her speech, she explained how Lal Ded’s sayings were essential to reconcile communities out of the political turmoil of the 14th century. “In the political turmoil of the 14th century, she represented the civilised human values and the common Hindu-Muslim culture – the Kashmiriyat – for which Kashmir has always been known. Hindus and Muslims became her followers. She became the beloved Lal Ded to both communities.”

It is difficult to tread this path of reconciliation when communities across the world are increasingly advised to close their borders and encouraged to insulate themselves from others. In times like these, it is important to turn back to Lal Ded’s vaks, to Nayantara Sahgal’s works.

In fact, she tells me that her new novel will be published next year. Her last novel, When the Moon Shines by Day, published last year in August 2017, has been longlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature as we speak. What is new novel called? The Fate of Butterflies. “You’ll know why the title is such when you read it,” she tells me.

Lal Ded’s Vaks

Translated by Ranjit Hoskote

88.

Whatever I’ve started, I’ll finish.

But the accounts are someone else’s headache.

Keep the reward, whatever I do is an offering to the Self.

Wherever I go, my only burden is lightness of step.

*

111.

What the books taught me, I’ve practised.

What they didn’t teach me, I’ve taught myself.

I’ve gone into the forest and wrestled with the lion.

I didn’t get this far by teaching one thing and doing another.

*

142.

Don’t think I did all this to get famous.

I never cared for the good things of life.

I always ate sensibly. I knew hunger well,

and sorrow, and God.

*

146.

Wear the robe of wisdom,

brand Lalla’s words on your heart,

lose yourself in the soul’s light,

you too shall be free.

*