Art is powerful. Things can be told with a glimpse that make one’s chest heave. In Budapest, during World War II, the Nazis and their Arrow Cross militia captured people – Jewish people – and brought them to the edge of the Danube River. The Nazis asked them to remove their shoes, then shot them – the bodies dropping like leaves into the river. The number of those killed, on the Pest side of the River, and elsewhere in the city between December 1944 and January 1945 is 20,000. The Red Army of the Soviet Union liberated Budapest in February. About a decade ago, the film maker Can Togay and the sculptor Gyula Pauer placed sixty iron shoes on the river’s edge to commemorate the murders. Seeing these shoes gives one a deep sense of the enormous crime of fascism. Nothing more needs to be said. One can see the rest in one’s heart.

Shoes on the Danube Bank

When I first encountered the photographs taken by Shahidul Alam, I thought of this sculpture on the banks of the Danube River. There is nothing that directly connects Shahidul Alam’s work with that of Gyula Pauer and Can Togay. They work in different mediums, with different themes. And yet, there is a straight line between this kind of art – which reaches deep into one’s fragile conscience and asks one to a simple question: what would you do if you were there? How would you react?

How would you react when you saw – for instance – this iconic picture taken by Shahidul Alam of people of the Rohingya community sitting in a cyclone shelter inside Bangladesh in 2017?

People of the Rohingya community in a cyclone shelter, Bangladesh, 2017.

These are people who have fled the most atrocious acts by the Myanmar government and by various militia groups, travelled across dangerous terrain into Bangladesh and then found themselves in camps the size of small towns with little protection. Some of the people are looking directly at the camera. No one is smiling. What is there to smile about? The look is beyond longing. They do not plead for anything. They are sentinels of a tragedy; whose lives barely register in the circuits of globalisation before their expulsion from Myanmar and now merely enter the log books as another in a series of tragedies.

In Alam’s book – My Journey as a Witness (Skira, 2011) – he talks about his time in another cyclone shelter, this time not a shelter that doubles as a refugee camp, but a shelter used in the aftermath of the 1991 cyclone.

Mother and child in the Bangladesh cyclone of 1991.

Alam recounts an incident that stayed with me. He is a photographer of the frontline. He went out to document the cyclone and its aftermath, which meant that he was there inside the shelter as the wind blew furiously outside. There was a knock on the door. A man came in. He asked for a bidi (a country cigarette). Alam got angry with him, ‘Can’t you see what’s happening here? The state people are in? And you want a smoke?’ The photographer has become one with the people. There is decorum in the shelter. The man’s needs seem superfluous. But then, the man answers, ‘Agaro jon re puita aisi. Biri de’ (I’ve buried eleven. Just hand me a biri). Alam’s depiction of the mood is powerful, ‘He wasn’t cruel, but his stare was cold’.

There is no need to be romantic about desperation and desolation. Human emotions are complicated, the experiences of the wretchedly poor who are most impacted by natural disasters and by state-engineered disasters cannot be graphed onto a bourgeois compass. Alam’s art captures the hardness and the humanity, the really difficult experiences of people and their often-unexpected triumphs. I am thinking of Shahidul Alam’s project to document Bangladeshi migrant workers who travel to Malaysia. Here, one sees the viciousness of capitalism crash against the hope – often naïve – of the workers. But then, despite the callousness of the State and the Business World, there is the the genuineness of the workers towards each other. To survive, they have to – on balance – be kind.

And to struggle.

A glance through the pictures by Alam which are in his book show his camera pointed often at people who are in the midst of difficult attempts to make the world a better place. There is a beauty here, a gesture of some in a protest, a fist raised, the neck muscles taut, the sinewy features of a brave woman alert to the rights of her people against an authoritarian state.

Democracy Movement, 1987-1990.

There is a story about these pictures that tells you a little about how Alam’s art comes out of popular emotions and how it returns to them. It is the day of that the military dictatorship ended in 1990. Alam and his colleagues spent the night working on their pictures, intending to pin them up to the walls of the Press Club. They knew that the police would take them down, but they also knew that some people would see the pictures. General Ershad’s government fell. The pictures stayed up. Four hundred thousand people came to see these pictures over the course of three and a half days. ‘We had a near riot at the door’, Alam writes. ‘They were hungry for images’.

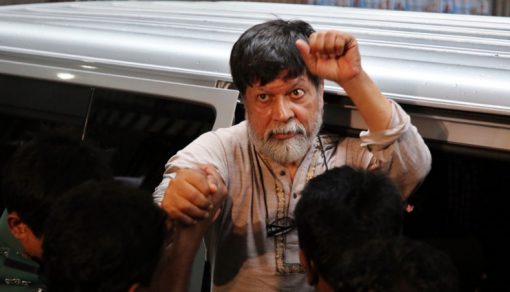

Shahidul Alam has been behind bars for the past month because he documented the latest struggle – the fight of the people in Bangladesh for traffic safety and so much more, so very much more. Arundhati Roy, Eve Ensler, Naomi Klein, Noam Chomsky and I released the following statement on the first anniversary of his arrest (on September 5):

Shahidul Alam, the recipient of Bangladesh’s highest cultural award, remains in prison. He was arrested on August 5, a month ago. People from around the world have written in support of this important photographer, yet the government of Bangladesh is impassive. He has been charged under Section 57 of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act for his role in covering the protests by young people in Dhaka (Bangladesh) for road safety. Others have received bail, but he has not – his bail hearings repeatedly cancelled. The State appears to be framing new malicious charges against him. We urge the government of Bangladesh to urgently release Shahidul Alam and drop all the cases against him. In 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the leader of Bangladesh’s freedom movement and father of the current Prime Minister, said – I have given you independence, now go and preserve it. We urge Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed to honour her father’s words. To preserve independence means to preserve the freedom of the press. Free Shahidul Alam.

This week, the courts denied bail once more. The voice of Shimul Billa Yousef rings once more across Dhaka – Bichar poti tomar bichar korbe jara, aj jegeche ei jonota (O judge, the people have risen. It’s now the day of your judgment). Governments are afraid of art. It touches us deeply – moves us to want to do something. It is why artists are so frequently killed and imprisoned. ‘Art is not a mirror held up to reality’, said Brecht, ‘but a hammer with which to shape it’. Such is the camera of Shahidul Alam – a hammer.