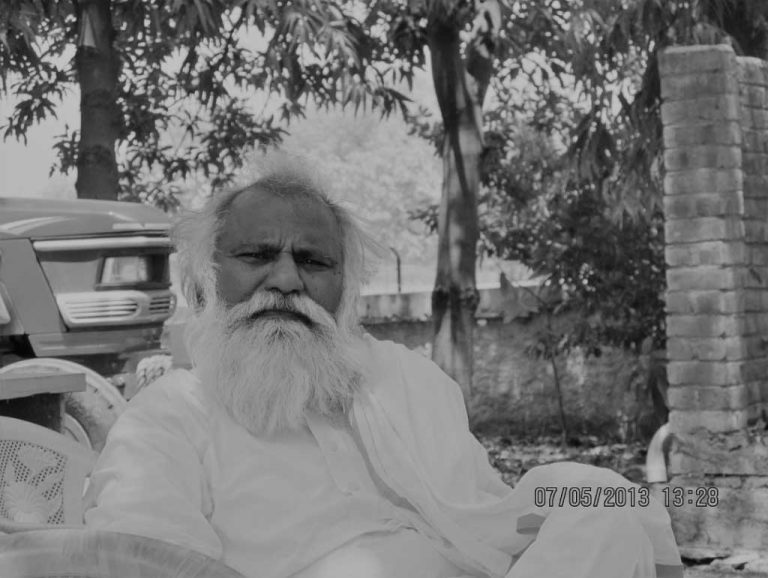

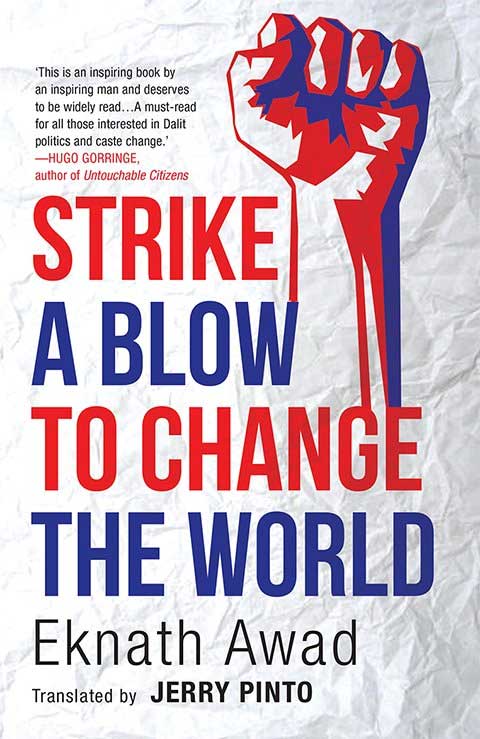

Dalit activist, Eknath Awad, wrote his memoir, “Jag Badal Ghaaluni Ghaav” in Marathi language, which was published by Samkaleen Prakashan, Pune in 2012. It has now been translated in to English by Jerry Pinto.

Eknath Awad was born in a low caste Mang family in Marathwada region in Maharashtra. The family was living a life of stigma, deprivation, discrimination, exclusion and above all the caste based violence perpetrated by the Brahmanical Social Order. He was respectfully called Jija, senior uncle, by people. Dr. Milind Awad, Eknath Awad’s son, while writing an introduction for the English translation, aptly describes his father’s autobiography thus,

“His autobiography is a sociography of caste-ridden rural Marathwada. The villages where he lived and worked, and of which he speaks, mostly have a non-Brahmanical social composition but have inherited vicious caste hierarchical practices and therefore developed inhuman brutalities that parade as living structures, all rooted in Brahmanical ontology. Jija’s life and activism can be seen as a series of responses to this situation”. (p. ix)

He was born to a Potraj, whose name was Dagdu. A Potraj was a religious mendicant who was devoted a goddess such as Laxmi or mari-Aai, who was allowed to beg and when given alms would take the karma of the donor’s sins upon himself and then would expiate them by cracking a huge whip around himself.

While reminiscing Eknath wrote, over the last twenty-five to thirty years, I have crossed paths with about fifty thousand Dalit families. We came together to struggle and the sutra for our struggle was,

“Over me Bhimrao left a banner unfurled,

Strike a blow as will change the world” (p. 3)

Eknath’s father wanted him to become a Potraj like him and help the family in carrying out the tradition of being a Mang. But his mother and sister fiercely opposed this idea and wanted Eknath to get education and become big in life. It was to be a tough task and the family had to endure to get him educated as they were living a life of destitute. Overcoming all the hurdles Eknath did manage to pursue education and break out from the traditional caste work that he would have ended with. The journey of pursuing an education was fraught with state of helplessness too. He described his situation in these words,

“Even if I had studied, I would not have got an ordinary office job. At that time, however much a Dalit studied, no one would hire him. There was no one to encourage or empathize with a promising and educated Dalit. Thus my ambition was limited to getting a government job. But it was important to finish my education in order to achieve that aim. And to do that I needed money. I sometimes found manual labour in the village and sometimes I didn’t. I would weave ropes and sell those. But that didn’t bring in enough….there was an endless shortage of money. Sometimes a storm would burst in my head. I would think: enough of this education. But then I would realize that if I gave up on studying, I might have to fall back on Mangki, the traditional caste work, and that would mean returning to a state of helplessness” (p.45).

With little support from here and there and through the government scholarship money he was able to pursue his education further. Study and struggle were going on simultaneously in his life. He had to save enough money to send home as well. Around the same time he got involved in the Dalit Panthers movement. This was also the time of the struggle to rename the Marathwada University after Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. The young and educated Dalit radicals were spearheading this movement across the Maharashtra state during the decade of 1970s. Involvement into Dalit Panthers activities made Eknath to read and understand Ambedkar’s clarion call for Educate! Agitate!! Organize!!!. These were like the foundation rock on which he was to build his future upon. The Dalit Panthers movement and the subsequent Renaming of Marathwada University movement caused severe backlash from the caste Hindus. These events made Eknath grew more strong in his resolve to fight against the systemic injustices that were being meted out to Dalits in his area and in other parts of Maharashtra as well. Houses being burnt, Dalit being killed, Dalit women being raped, Dalits in general being discriminated against had a deep impact on young Eknath

Around the same time his mother passed away after a brief spell of illness. With not enough money to cremate the family decided to bury her dead body in the village. With mother gone he would often remember how his mother would sing a song while grinding the jowar,

“My son alone can take on a panchayat of ten

Now he will bring us to rest in the shade”. (p. 56)

Eknath would feel as if “his mother wanted him to bring justice to the people; she wanted him to help the poor and raise the downtrodden. This was her dream as she ground the jowar of our poverty; how did she keep her dream so big?” (p.56)

His mother’s dream and aspirations and also the inspiration that he derived from the long history of struggle led by Jotiba Phule, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Annabhau Sathe and others remained the beacon lights for him throughout his life.

After facing much problem in trying to continue with his studies, Eknath started working with Vidhayak Sansad, a socialist group, on issues related to bonded labour among the Adivasi community at Dahisar near Bombay. As it generally happens in such kind of social work, Eknath and other members of Vidhayak Sansad had to face the wrath of the status-quoist forces in the region including violent attack on them. With much persuasion and hard work they were able to help Adivasi labourers getting released from their bondage and start a new free life. After working for about two years there he was still restless about going back to Marathwada region but had no clear idea about how that could be made possible. Vivek Pandit of Vidhayak Sansad and Pravin Mahajan from Oxfam helped him in relocating to Ambajogai in Marathwada region with Manavlok, a self help group. But after some time he had to go back to Vidhayak Sansad again. By this time, Vivek Pandit had started the Shramjeevi Sangathana (Labourers’ Union). They started working on Adivasi people’s right regarding the forest land. While working for Adivasi rights he was able to understand their situation quite well, but at the same time, he was still looking for ways and means to start his own work on issues related to Dalit’s dignity, rights and livelihood.

Life was undertaking its own twist and turns. On a chance encounter with an old friend from his MSW days, he came to know about an opening with CASA (Churches Auxiliary for Social Action), Mumbai for the post of Social Worker. He applied for it and was called for interview. Interview turned out to be quite good and he was offered the position of Field Officer instead of social worker with one thousand rupees per month as his remuneration. Eknath described this sudden turn in his life in these words,

“One thousand rupees a month and a post that exceeded my expectations! I was delighted but there was one problem. I did not want to live away from my village now. I explained my position, my problems, my father’s illness, my scattered family and asked if it would be possible for me to work out of my village. The answer was: ‘Okay, from now on Dukdegaon will be the regional office of CASA; and you will be in charge of the Dukdegaon office’. What more could I have asked for? It was as if a blind man had asked for one eye and had been given a pair”. (p. 117)

This was a turnaround in Eknath’s life that was going to change the entire course of life, his work and his mission altogether. He was appointed Field Officer in charge of Marathwada and Western Maharashtra region. And his responsibilities included selecting workers at the village level, starting new programmes in the villages and implementing other programmes of the organization. The work area included six districts in Marathwada and six districts in Western Maharashtra. A new life of an activist began as his earlier work experiences and the perspective that he had developed were going to give a new shape to his work.

With CASA’s help Eknath started Dalit’s right to cultivate on the Gaayraan land (common land reserved for cattle’s pasture), and this normally belongs to the government. He had to organize Dalit landless workers to stake their claim and also approach government revenue officials to clear hurdles in getting possession of the land. At the same time, CASA would also intervene to help them with providing initial stage financial needs for starting the cultivation. Very soon they also started food for work schemes which helped people in those areas tremendously. More than three hundred bore wells were dug to help them for cultivation purpose. Apart from these works which were basically meant for creating livelihood opportunities, Eknath also started programmes like Dalit Awareness Meetings, and Rights Awareness Meetings in those areas. As part of the awareness raising programmes theatre and music groups also became an essential elements aimed at making people understand the need for bringing change in their life.

With CASA’s help, Eknath was able to support and groom many organizations in the area focusing on youths and women issues. He also started his own organization- Gramin Vikas Kendra- Rural Development Centre (RDC). A micro-credit women’s self-help also started functioning in Dukdegaon. Marathwada being a draught prone area, water shortage was big problem there. Women in the area had to walk several kilometers to fetch water. Along with local support, RDC was able to construct a lake for some of the area’s need for water. Similar activities were taken up in other areas as well. This region was also known for sugarcane cutters being exploited by contractors. RDC took note of this problem and was able to resolve it with people’s help. Community based mobilizations continued during this period. Six years of working with CASA brought many changes in Eknath’s life and work.

Working against casteism became a necessity and it spurred the idea of forming campaign on human rights issues. The graded inequality which is the hallmark of the Brahmanical caste system had been and continued to be a normal aspect of inter and also intra caste relationship across Maharashtra and other states in India. There was a general agreement among activists working with Eknath to start something new. That is how ‘Maanavi Haq Abhiyan (Campaign for Human Rights) came into existence. Eknath Awad thus explained,

“Setting up Maanavi Haq Abhiyan was a turning point in my life no doubt, but also brought about a change in the lives of countless people. A golden age began in my life. I was chosen as the main Convenor of the organization… The first of the organizations camp was held at Vasai. Fifty activists from Marathwada attended the camp. We familiarized the participants with the method of work, the procedures and the decision making processes of the organizations. In order to establish our own, we studied the work done by the Vidhayak Sansad; we interacted with their activists to find out how they had discovered the issues that needed to be tackled, how they should be resolved, how people had to be brought on board. Vivek-bhau, D. R., the Socialist leader Sadanand Varde, Sangeeta Koparde, Vidyut-tai, Rs Vi Bhuskute, Da Go Prabhu, Shelapkar and I comprised the trainer’s team. Many experts came to talk about various laws. We were like fields that had been ploughed and sown and were waiting for the rain”. (p. 175)

It was decided to have an inaugural programme on World Human Rights Day (10 December) as caste practices were proving to be a stain the nation’s human rights record. A ceremonial announcement of Maanavi Haq Abhiyan’s presence was done through organizing a state level conference, ‘Niradhar Parishad’ at Mumbai on 17 December 1989. Several Dalit and Adivasi activists attended it. Justice P. N. Bhagwati, the retired Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, who was the chief guest at this conference gave a pledge:

“I will always endeavour to sow in society the values of equality, independence, brotherhood and justice that are enshrined in the Constitution of India. I will not bear atrocities committed upon women in my society. I will dedicate my life to fighting these atrocities”. (p. 176)

The movement gained momentum over the years. Maanavi Haq Abhiyan was able to galvanize local level activists, train them in the nitty-gritty of the laws and that is how a fairly large number of activists were made available though para-legal trainings camps in Marathwada region. On the other hand people belonging to Dalit, Adivasi and Denotified Nomadic Tribe community started giving up on their dehumanizing caste practices. Eknath and other activists involved in Maanavi Haq Abhiyan had fellowships from Oxfam.

When Eknath’s father passed away, he was not at home. He was in fact at a Police Station in Parbhani, trying to get some arrested sugarcane workers released. Somehow he got to know and reached home. Most of the time he was out of home and his wife was taking full responsibility for family. His eyes were fixed firmly on the Dalit struggle. Around same time, he came to know about a new legislation, “Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 passed by the Indian Parliament and notified by the Government of India. This information was shared with him by a high level government official. But this new Act had to be first adopted in the Maharashtra State Assembly before it could be implemented in the state. Maanavi Haq Abhiyan took up this as a challenge and also an opportunity to force the Government of Maharashtra to place the Act in State Legislature and get notified in the Government Gazette. Somehow Eknath Awad and Maanavi Haq Abhiyan team managed to reach and barge into the Chief Minister’s Office and started slogan shouting. On seeing them enter like this the Police officials came forward to hold them back. But CM told the Police not to stop them. Eknath Awad explained the purpose of their visit like this and sought time to discuss the matter. They were given time to come at 16.00 hrs the following day. He directed the Police to release them after some time. When they met the CM they were able to convince him for introducing this new Act and also to ensure its implementation. The Act was introduced in the State Legislature and subsequently notified too. The Chief Minister sent a copy of the new Legislation and a personal letter duly signed by him to Ekanth Awad about this.

Getting the new legislation introduced and notified brought new challenges for Maanavi Haq Abhiyan. They took this as an opportunity to train their local activists about provisions of the new law and also at the same time insist on its implementation by police and administrative officials. The work load of Maanavi Haq Abhiyan increased manifold. All important information had to collected and suitable strategy to be adopted in their fight against casteism and caste atrocities.

In the year 1991, when the Government of India and also the Maharashtra State Government were celebrating the Centenary Birth Anniversary of Dr. Babasaheb B R Ambedkar, the Maanavi Haq Abhiyan released a status report on situation of untouchability and caste based atrocities along with discrimination and exclusion faced by Dalits and other disadvantaged groups in Marathwada region. This report was prepared by the social work students of Mumbai based Nirmala Niketan School of Social Work in association with Maanavi Haq Abhiyan. It was widely disseminated through media and also through public meetings to create more awareness about problems related to caste based discrimination, exclusion and violence.

On a mission to get the new law implemented and end the scourge of caste based violence, Eknath Awad and Maanavi Haq Abhiyan members in particular were becoming target of Caste Hindu and other status-quoist forces treachery in Dukdegaon and other areas in Marathwada. They had to wedge battles on many fronts to ensure the rule of law. This was not an easy task. Violence was reported on a regular basis and many times the courts of law had to be approached to get justice.

As times were passing by, his village gained the status of a village Panchayat. The people of Dukdegaon convinced him to allow his wife Gayabai Awad to contest for the post of Panchayat Sarpanch (President). Gayabai was popularly elected and served for three terms (15years). Later on she was also elected to Zila Parishad (District Panchayat) for two terms and was made chairperson of health committee. She is still active in many ways.

Eknath Awad also started Ramabai Ambedkar Non-Agricultural Cooperative Society. Women from the Vanjara, Maratha, Laman, Muslim and Mang communities participated in the work of this organization. This cooperative had by the year 2010, affected the lives of twenty lakh families. Apart from Dukdegaon where the population was barely a thousand, women from other neighbouring four/five villages started becoming active members of this organization. They used the money to start small provision stores; they began animal husbandry or bangle selling enterprises; they took to selling fish or dealing in livestock and setting the small pan stalls.

Remembering the long drawn out struggle days and the transformation that had taken place over the years, Eknath thus described the situation

“Our work had transformed the village. And the movement was expanding in scope. The Maanavi Haq Abhiyan had become the representative of Dalit pride. Many lives had been transformed by it. With me, other activists had grown and developed. Their faces pass before me now. I have seen their lives turned right around. So many have made huge strides and have taken the movement forward with them”. (p. 223)

1993 earthquake at Latur in Maharashtra brought the caste fault-lines in prominence once again. Maanavi Haq Abhiyan members became part of the rescue and rehabilitation on a war footing. They got a great deal of assistance from Oxfam once again. For the next three years they were involved in the assistance programme to earthquake survivors. Maanavi Haq Abhiyan wanted the reconstruction of damaged villages by disregarding the traditional old caste practices, but the Government of Maharashtra had to bow to pressures from dominant caste and communities and that is how the old tradition of caste segregation was maintained.

In the year 1994 Marathwada University was renamed as Dr. Babasaheb B R Ambedkar Marathwada University. A dream after a long drawn out struggle became a reality. Dalits were overjoyed, but the Caste Hindus expressed their anger by attacking Dalit hamlets, beating up of Dalits and also by burning and looting of Dalits households in several parts of Maharashtra, but more so in Marathwada region. Once again with a generous support from Oxfam, Maanavi Haq Abhiyan was able to provide relief to affected Dalit families.

How should one respond when one is faced with a death like situation? Eknath always used to believe that in the fight again injustice one should be prepared to face all kinds of threats including deadly attacks on their life. He had become immune to such threats over the years. But these threats would come up again and again. He faced them quite boldly. Never ever he bowed down to such intimidations. Rather he worked with more enthusiasm and personal commitment.

June 04, 2004 was one such bloody day for him. Like a typical Bollywood Masala film, Eknath was attacked by a group of sword and daggers wielding men. He fought bravely. A sword slashed at his chest; another one on his shoulder and the third attack on his back. His shirt was soaked in blood but he kept charging on the assailants. The assassins ran towards the police station and got themselves locked up. Large number of people had gathered there while this deadly attack was happening. They followed Eknath Awad to the police station. He asked his followers to calm down. He was shifted to Civil Hospital at the Beed district headquarter. People were angry and spontaneous violence broke out in many places. He was admitted to ICU as he lost lots of blood and lost consciousness too by that time.

Next day this deadly attack was widely reported in local and state level media. Large numbers of people had gathered in front of the hospital eagerly waiting to see their leader Eknath Awad. The Doctors attending to him worked hard to save him. On gaining consciousness, with his body, nose, hands all swathed in bandages and one arm strapped to his chest, Eknath came o

“I have faith in my country’s Constitution, the Constitution that Babasaheb has given us. The enemy wants us to lose control, to give into rage. Do not bring shame to our movement. I am healthy and fit. I have the strength to withstand ten such attacks. Be calm, be peaceful. Do not lose your balance. Jai Bhim”. (p. 252)

While convalescing in the hospital, Eknath Awad had for the first time spent much time thinking about himself, his family, the injustices meted out to Dalit people and in this introspective mood he was moving towards the question of searching of paths for liberating himself, his family and Dalit people for whom he has been working from a life filled with misery into a life meant for enlightenment. And it was here that he came much more closer to Buddha and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. After coming out of the hospital, he started a new campaign- ‘Let us make our way to the Buddha’. He was clear in his mind that it would not be an easy campaign. Conversion to Buddhism must be undertaken with a sense of responsibility. Massive awareness campaigns were organized through Dhamma Parishads and other interactive session in villages and districts across Marathwada region. And finally on October 02, 2006, people belonging to different castes and denotified tribes like Mangs, Pardhis, Kaikadis, Bhils and others they entered Buddhism. Bhante Surai Sasai of Japan gave them the diksha. Eknath thus averred,

“Religion fulfills a human need. In the social environment in which we live, religion gives us meaning. But what about carnal/physical questions? Conversion does not provide all the answers, nor does the battle end. It offers a theoretical basis for it but the struggle does not end and only when the scenario changes- along religious, social and political axes- will the Dalit struggle end. Unless we address the fundamental causes, we will never secure respect for the Dalit”. (p. 263)

It was a realization that dawned on Eknath and others who were part of his movement once again to concentrate on and intensify the struggle for land rights of Dalits and other marginalized people. It was in 2001 when the centenary Birth Anniversary of Dadasaheb Gaikwad started that a Gaayraan Parishad was organized in which five hundred activists were invited for a two day brain storming session to debate and discuss ways and means on the issues of landless peasants struggle. Zamin Adhikar Andolan (The Land Rights Movement) thus began. As a result of this several other organizations became part of Land Rights Movement.

Securing land rights to Dalit and other marginalized groups in itself was not enough. They needed financial help not only to cultivate, and irrigate but also to sale their agricultural produce in the market. With this realization the Savitribai Phule Mutual Benefit Trust was set up on December 10, 2009. Its original intention was to focus on the women who tilled the common land for this saving group. In the first level, the scheme had a favorable response from five districts. And then they did something that had never been done before in the fight for the rights of the landless: they set up a bank for the landless women labourers.

Anik Financial Services Private Limited for landless women was set up. Economic assistance was granted by the Oxfam to start the company. The Savitribai Phule Mutual Benefit Trust was merged into this. Approximately about 2.75 crore worth of loans were disbursed. They were also seeking permission from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to grant them the status of a bank. The target was to touch the lives of ten crore families. Fifty percent of the directors of the bank were women. And the ultimate plan was to make it an all women director’s bank.

Eknath Awad made forays into political field as well. He contested the Lok Sabha Parliamentary election from Beed in 1996 on a Bahujan Samaj Party ticket. The election proved decisive for him personally. He became much more popular after that for his commitments towards the cause of Dalits and other disadvantaged groups in the area.

Whatever had been achieved during his life time, Eknath Awad would still remind himself and others to the fact that until the Dalits can live a life of self respect, there is a need to continue fighting. Towards the end of this amazing life history he summarized his role in these words,

“A seed of the thoughts of Phule and Ambedkar was planted in me. A vine grew in my head. From that seedling, a peepal tree began to grow. Around that tree many activists twined themselves as creepers do. Those vines I had planted at the huts of the Backward Classes and Nomadic Tribes have begun to climb their trellises…” (p. 282)

Facing all the trials and tribulations that came his way, he took the world in stride and accomplished many of the impossible goals. His life was indeed a life spent in struggle for emancipation.

He passed away on May 25, 2015.