Reading Note by Note is like looking into the old-fashioned bioscope where the vignettes of India’s story over the past seven decades are played to Hindi film music.

If India didn’t exist, no one would have the imagination to invent it. It was that bold and radical an idea, well ahead of its times in 1947. Jawaharlal Nehru’s evocative description of India as ‘an ancient palimpsest on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed, and yet no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously’ often masquerades the astounding fact that 1947 did represent a major break from the past.

Not only was this land mass brought together as India for the first time, a people beset by poverty, massive illiteracy and with such huge diversity on a subcontinental scale chose to be a democracy. The ideals did not emerge suddenly but were rooted in the decades-long movement for independence, which has no parallels in its audacious idealism and willingness to dream.

1947: Afsana Likh Rahee Hoon

Afsana likh rahee hoon

Dil e beqaraar ka

Aankhon mein rang bhar ke

Tere intezaar ka

Lyricist: Shakeel Badayuni

Music: Naushad

Singer: Uma Devi

Film: Dard

TIME froze, in the meltdown that was 1947. The British packed their bags and rolled out, back to Blighty. And a dawn of unbelievable possibilities broke out in India.

A luminous morning that promised the bright light of freedom did not come without its shadows. The clouds hovering above may have been darker than what India’s founding fathers had hoped for. They carried in them the agony of Partition, the pain of separation as the country was divided into two nations: India and Pakistan. But the phrase ‘the empire on which the sun never sets’ got a fitting burial, well after dark on that day in August.

Yes, 15 August 1947 did spell Freedom in several languages: Swatantrata, Azaadi, Sudandiram, Swadhinata. It was no Russian Revolution and India’s transformation would be stuck with the label of being a social democratic one. But there was little to be sanguine about that day.

It was a new day and a new way.

‘Afsana likh rahee hoon’ is arguably the most memorable melody of 1947, it is hummed – with a familiar ring to it – even today. It is anything but easy to pick a song that tells or encapsulates the 1947 story. Events headier and more surprising than a Bombay blockbuster were unfolding in real time in the subcontinent. The afsana (story) of India itself would begin to unfold this year. And what a start it got too. In August, Mahatma Gandhi and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan were in Calcutta trying to stop the communal mayhem and Jawaharlal Nehru was in Delhi. Each hoping to cement the idea of a modern India amidst all the turmoil – both together, yet apart.

So – midwifed in both agony and hope – did India’s afsana get under way.

2017: Safar Ka Hi Tha Main Safar Ka Raha

Jab se gaon se main shehar hua

Itna kadwa ho gaya ke zehar hua

Safar ka hi tha main safar ka raha

Lyrics: Irshad Kamil

Music: Pritam

Singer: Arijit Singh

Film: Jab Harry Met Sejal

WHEN Imtiaz Ali makes a film, there are certain features to be expected: a lead couple with a complicated, hard-to-define relationship; a journey; and Irshad Kamil as lyricist. Jab Harry Met Sejal in 2017 was another one of their collaborations and unlike his previous three films, Ali chose Pritam to compose the music for his film, and he did not disappoint.

In ‘Safar’, Irshad Kamil wrote a contemplative, philosophical song that did not have the structure of a usual film song. Only the refrain, ‘Safar ka hi tha main, safar ka raha’, keeps the listener grounded as Kamil expresses the internal fears of an individual’s never-ending journey. The lyrics reflect Kamil’s skills as he weaves deep lines like ‘Jab se gaon se main shehar hua, itna kadwa ho gaya ke zehar hua’ (as I evolved into a city from a village, I became so bitter, got toxic) with consummate ease. Composer Pritam allows the thoughts to run unhindered in the song as he gives it a gentle cloud of guitar and percussion to float on. Arijit Singh then sings it as if intoxicated and it becomes a song for the ages.

For India, the year 2017 started in a daze as the country was still suffering from the effects of demonetization of ₹500 and ₹1,000 currency notes, announced on 8 November 2016. Even as evidence kept piling up about the ill effects of this move, the Narendra Modi government kept devising new justifications for it. From the initially declared aim of fighting black money and corruption, the government moved to fighting terrorists, expanding the tax base, pushing for a cashless economy, formalizing the informal economy, bringing ‘idle’ savings into the banking system and fighting the menace of counterfeit currency. In August, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) released figures that showed that 99 per cent of all demonetized currency had been deposited in banks.

Even as the aim of this exercise remained fuzzy, its effects were clear. With cash sucked out of the economy for a prolonged period, all economic activity came to a halt or slowed down considerably. This was reflected in India’s GDP growth, which slowed down to only 6.1 per cent in the fourth quarter of the financial year 2016–17. The impact was the worst on investment demand in the country as it contracted by 2.1 per cent in the last quarter. The Indian economy had been dealt a severe and entirely man-made shock whose negative effects were felt all over.

The year also saw keen electoral battles in various states across the country. Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab and Goa went to polls in February while Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat voted in the month of December.

In Uttar Pradesh, the ruling Samajwadi Party allied with the Congress while the BJP and BSP went alone. In Punjab, the battle was a three-way fight between the ruling SAD–BJP combine, AAP and the Congress party. In Uttarakhand and Goa, the real battle was between the Congress and the BJP. In UP, Prime Minister Narendra Modi campaigned aggressively and the BJP romped home with a huge majority. Adityanath, the Gorakhpur MP and head priest of the Gorakhpur math, became the chief minister of the most populous state in the country. In Uttarakhand too, the BJP trounced the incumbent Congress party comprehensively.

The story was different in the states of Punjab and Goa though. In Punjab, the Congress won a hard-earned and big victory over the AAP against predictions while in Goa it emerged as the single largest party with seventeen seats in the forty-seat assembly but was not allowed to form the government. The BJP with thirteen seats was invited to form the government. Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar returned to state politics and became the chief minister of Goa.

As the BJP kept adding states to its kitty, it also caused a rethink in other political parties about their prospects. The biggest example of this was set by the Bihar chief minister, Nitish Kumar. In July, Nitish Kumar terminated his grand alliance with the RJD and the Congress party. He resigned as chief minister and then joined hands with the BJP in the state. He was sworn in as the chief minister again with BJP members as part of the cabinet as well. This was a significant setback to opposition politics barely two years before the next general elections.

After years of planning, debate and bargaining, India saw the Goods and Services Tax (GST) being introduced in the country in the month of July. The GST had been in the works for a long period. It was ironical that the Narendra Modi-led BJP government pushed for the rollout of the tax though the BJP had resisted its implementation when in opposition. The objective of introducing the GST was to simplify the indirect taxation regime in the country, which was considered to be one of the most complex in the world. GST was supposed to simplify filing tax returns and thereby improve compliance but that was not to be as the government pushed for a more complex GST regime than what was prevalent in the rest of the world.

Experts warned that the IT systems required to ensure a smooth rollout were not in place and the structure was too complicated to understand or comply with but the government chose to ignore these protests. The result was a mess as businesses tried to comply with the new regime. The Indian economy that had not yet recovered from the jolt of demonetization suffered yet another setback with the hasty implementation of GST. Small and medium enterprises suffered the most.

In the month of June, India got embroiled in a border faceoff with China. The stand-off began when China started constructing a road in the Doklam plateau. The area was a disputed territory between China and Bhutan. Indian troops entered the area to prevent the Chinese from constructing the road. China asserted that the area was its territory and asked India to withdraw. After a tense seventy-three-day stand-off, India and China announced a disengagement from the site. Indian troops withdrew to Indian territory while Chinese troops started building temporary and semi-permanent infrastructure a couple of kilometres from the area. The stand-off ended only to give way to a more permanent one with increased Indian and Chinese troop presence in the region.

The lines ‘Itna kadwa ho gaya ke zehar hua’ from the song ‘Safar’ might have been written about how bitter India had become. The hatred that had come to fore with the lynching of Mohammed Akhlaq in Dadri, UP, in 2015, reared its ugly head repeatedly in 2017 as well. Fifty-five-year-old Pehlu Khan, a dairy farmer from district Nuh, Haryana, was lynched by gau-rakshaks in Behror, Rajasthan, as he was returning to his village with cows that he had purchased in Jaipur. Six others were injured. The police charged the victims with cow smuggling. In June, seventeen-year-old Junaid and his two cousins were attacked in a train near Palwal in Haryana. Junaid was killed in a dispute over carrying meat in the train. The victims in such incidents were mostly Muslim. Dalits too faced the brunt of increasing atrocities. As the frequency of communal and caste violence increased, it led to an increasing sense of unease and insecurity among the minorities and deprived sections of society.

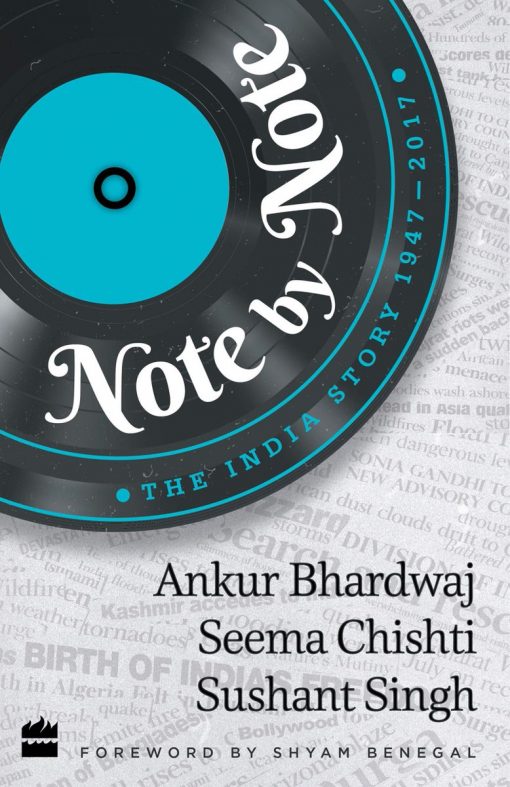

Ankur Bhardwaj is a journalist with Business Standard. Passionate about films, food and politics, he has an innate understanding of India because of his wide-ranging experience in myriad jobs dealing with technology.

Seema Chishti is a journalist with The Indian Express. Surrounded by politics, she is deeply interested in Indian society, its contradictions and its interactions across caste, caste and region and brings her understanding of society to her writings on Indian politics and culture.

Sushant Singh is a journalist with The Indian Express. He writes on matters of strategy, defence, foreign policy and politics. He has authored Mission Overseas, a book on three overseas missions of the Indian armed forces.