Baburao Ramji Bagul was born in a poor dalit family in Nashik District, Maharashtra. His education stopped after he completed his matriculation. Despite his poverty, he continued to write and remained active in dalit movement. He is regarded as a pioneer of modern dalit and Marathi literature.

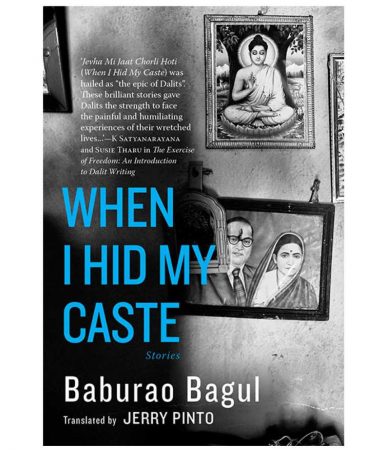

When I Hid My Caste is a collection of short stories depicting the lives of the people on the margins — rebellious youth, migrants, sex workers, street vendors, slum-dwellers and gangsters — all impacted by the vicious caste system. Originally published in Marathi (Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti, 1963), this book has been translated in English by award winning author and translator Jerry Pinto.

The following is an excerpt from the short story “When I Hid My Caste” of the book.

When I Hid My Caste

When the difficulties visited upon me after I concealed my caste come to mind, memory ignites furnace in my heart. My head begins to ache as if it is about to burst; in this luck-forsaken country, human beings should not be born as Dalits. If and when they are, they must bear such sorrow and such disrespect as would make death seem an easier option, making a cup of poison a Dalit’s best friend. For even nectar rots in one’s heart and what is left is a rage, sharper and more cruel than a sword. This is the extent of the mental and emotional atrocities that I had to bear. If I had continued to live there, continued to hide my caste, the anxiety would have driven me mad. And so it was a good thing that I came to Mumbai, for on the night of pay day, at Ramcharan Tiwari’s home, I was robbed. And one of the thieves had announced that I had been hiding my caste. And Ramcharan Tiwari beat me to his heart’s content. And Kashinath Sakpal saved me from that immense rage. This is how it came about. At first light, I got down at Udhna Station and was walking to the engine shed. The joy of having got a job had made my mind as frisky as spring, as brave as rain. This sense of well-being had left me with no fear of anyone. No man was a stranger. I had not a care in the world. I was sure that every word I spoke would bring victory, every step I took would bring springs of fresh water spurting from the ground. For I had spent the night in the train, dreaming up a wonderworld of happiness.

So there I was, flowing like a morning breeze, when I saw a group of workers in front of me and called out to them, bringing them to an abrupt halt. From among them, Boiler-Fitter Ranchhod asked in Gujarati, ‘What’s up, brother?’ In chaste and elegant Gujarati, I introduced myself.

Ranchhod was immediately ready to rent me a room and the workers with him began to look at me with admiration. They were taking in, with a look of awe, my coat, topi, dhotar, Kolhapuri slippers, the book of Mayakovsky’s poems in one hand and the trunk to which my bedding was tied. The respect on all their faces, their curiosity, all this added to the joy I felt in getting a job.

My mind, filled with this happiness, was like a woman dreaming of her lover. I could have got lost in all this happiness but then in a hesitant voice, Ranchhod asked, ‘…But what is your caste?’

I roared like a thunderclap on hearing this: ‘Why do you ask me my caste? Can you not see who I am? Me, I am a Mumbaikar. I fight the good fight. I give my life in the defence of the right. I have freed India from bondage and I am now her strength. Got that? Or should I go over it again? Do you want it in verse?’ Still buoyed up by my joy, I growled and walked on. For my mind dreamstruck, was already racing ahead of me.

Behind me I could hear the pair of them muttering to each other.

‘Arre Ranchhod,’ said Devji, ‘don’t let this one get away. Don’t lose the rent. He’s a Marathi maanus. And a fearless one too. Possibly a Brahmin, maybe Kshatriya. Call him back. Go. Run after him.’ But bruised by my attack, Ranchhod would not come

near me. He asked Devji to approach me on his behalf. Listening to this frightened chittering, I felt that all these people seemed small enough to fit into my pocket.Finally, Ranchhod made a tentative approach. ‘Now look here, don’t get angry. When we meet a stranger, we always ask him his caste. This is the way in our country.

I’ve as good as rented you the room. Will five rupees a month be okay?’

Devji interrupted: ‘Brother, one can eat mud with a caste brother, but one shouldn’t attend a feast with someone of a lower caste. A man like you is not going to live with some poverty-stricken dhedas, is he? Nor are you going to lose what you’ve earned by living with thieves.’

‘You shouldn’t speak that way in front of me, a new citizen of a new Bharat. We’re all the creators of the new nation. There are no dhedas, no poor, no Brahmins.’

‘My mistake.’ ‘Indeed a mistake, a mistake indeed. Words like that made a rich country like ours into a beggar. Got it?’ ‘Yes, but what about the room? Will you take it?’ Ranchhod was almost begging in his desperation. ‘I’ll think about it and let you know.’

‘Think? Think about what? It’s a lovely room. There’s a well near it, full of sweet water. And mango trees around it. Every day, you’ll see birds, birds of many colours. And you’ll have birdsong. Do we have a deal?’ His helplessness and this desperate sales pitch pleased me so much that

I agreed. Delighted, he issued an immediate invitation. ‘Let’s have some tea.’

‘Go on ahead. I’ll follow,’ I said. He obeyed, taking all the people he had with him. When we had crossed a line of railway bogeys, ducking under some, skipping past others that were being shunted away, we came to a grease-laden, soot-stained wagon in which they had a canteen that served tea and snacks. There wasn’t much room to sit inside. Even so, he rushed in and waved to me to enter and just as he was doing this, what should I hear but a voice like the cruel crack of a pistol-shot: ‘Mahar.’ ‘M’har?’ Ranchhod asked, turning his head and shrinking into himself. And my mind, which had been soaring like the Garuda*, was brought crashing to the ground. The joy, washing over my body, dried up. The tingly bubbles in my bloodstream evaporated. The words of our earlier conversation danced like demons in front of my eyes. I stood there, rooted to the spot, like a stone rammed into the earth. Someone in the canteen had found me out; he had picked me out as one might pick out a stone from raw rice. Even as I was trying to decide how to surmount this question, Ranchhod’s question fell upon my ears: ‘Tiwari, what does “Mahar” mean?’

And Tiwari replied from his half-knowledge: ‘Mahar means Maharashtrian. They are like Shivaji the Great; warriors.’ ‘No Panditji, not like that. I’m one of Dr Ambedkar’s party, of his caste. My name is Kashinath Sakpal, of Mumbai, Kala Chowky.’