Khan: Hum wahan hain jahan se humko bhi kuch hamari khabar nahi aati

Husain: Hum kaun hain, hain ya nahi hain, ye zer-e-bahas nahi hai, aap sirf iss baat pe tawajjah dijiye ki Qissa Urdu ki Aakhri Kitab ka, Ibne Insha ne likhi hai

Khan: Lekn wo toh marr gaye

Husain: Arre, phir toh maamla saaf ho gaya.

Khan: Wo Kaise?

Husain: Ab sarkar kiske khilaaf fatwa jaari karegi?

Khan: Bhai likhne wala marr gaya, sunane wala maujood nahi hai yahan par, phir to yahi (audience) phasenge.

Husain: Ye to pehle se hi phase hain.

Khan: Wo kaise?

Husain: Vote jo de diya!

Such sharp political comments peppered Danish Hussain’s latest satire, Qissa Urdu ki Aakhri Kitaab Ka, which premiered in Mumbai’s Prithvi Theatre last year. “Humara kaam iss baar shayad itna acha hai ki log hum par fatwe jaari kar denge,” he joked during an interview with the Indian Cultural Forum. At a time when anyone questioning the current ruling government’s policies is charged with sedition and labelled an “anti-national”, it is not unlikely that Husain’s political satire could earn him the state’s ire.

Husain received a joint Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for reviving the ancient Urdu storytelling tradition, Daastangoi. But, in October 2015, Husain, along with several other artists and writers, returned his Sahitya Akademi award in protest against the growing intolerance in the country under the current political regime.

The Humsub Drama Group, in collaboration with Ghalib Institute, had organised an Urdu Drama Festival from 6 to 10 July, 2018 in memory of Begum Abida Ahmed. She was the founding chairperson of the Humsab Drama Group, established in 1974 during a period of prolonged political turmoil in the country. As one of the speakers would later remark, one of the group’s most important tasks had been to counter the divisive ideologies of the time. The festival was inaugurated with Danish Husain’s Hoshruba Repertory’s production, Qissa Urdu ki Aakhri Kitaab Ka. The play is based on Ibne Insha’s classic text Urdu Ki Aakhiri Kitaab. Insha (1927-78) is considered one of the best humourists in the history of Urdu literature and is also known for his poetry and travelogues.

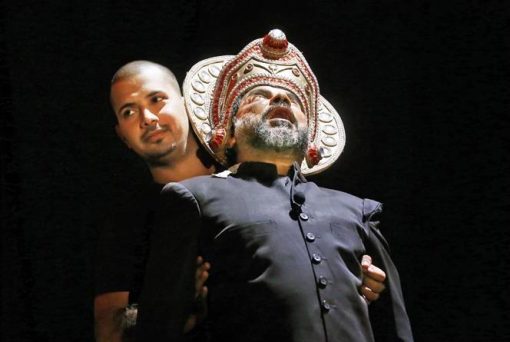

A two-actor farce performed by Danish Husain and Yasir Iftikhar Khan, who were accompanied by two musicians, the Hoshruba Repertory’s production retains the book’s framework but its content is adapted for it to better reflect the contemporary socio-political situation in India. Ibne Insha’s book is divided into chapters categorised by subjects (such as history, geography, moral science); each chapter ends with a set of questions, interspersed with Ibne Insha’s own poetry. The play also follows this structure, combining it with a mix of satire, stand up, storytelling, talk show banter, and farce, peppered with musical renditions of Ibne Insha’s poetry. It touches upon a number of contemporary issues — like censorship, hate mongering, rising intolerance, and the almost Kafkaesque socio-political situation that the country has found itself in – using an effective combination of humour and satire. “Pet roti se khali, jeb paise se khali, baatein waseerat se khali, waadein haqeeqat se khali, dil dard se khali, dimag aql se khali, shahar parwaanon se khali, jungle deewanon se khali, akhbaar khabar se khali…sab khali, ye humare yahan ka khalaai daur hai. Yaani ‘space age’, antariksh yug,” Khan’s character declares on stage, while expounding on the different “eras” in history. An example of how seamlessly the characters comment on the politics of our time while seeming to talk about erstwhile rulers is when Khan’s character talks about Akbar and how well loved he was. He comments on how this love was evident in Akbar’s followers’ wishes for him. “‘Aap hamesha mulq ke zille ilaahi bane rahein’, aise 2019 ya 2025 tak nahi.[…] Badshah Akbar ko ye naubat hi nahi aati thi ki wo apne mann ki baat karein, wo cheenk bhi dete ya paad bhi dete, to bhi unke himayati jaa kar press mein bayaan de dete. Parastish, yaani bhakti, khair uski misaalein aaj bhi dekhne ko milti hai, ye alag baat hai ki unhe deen-e-ilaahi nahi kehte hain”.

Even though the play dealt with a number of serious issues, the audience laughed its way through the play. “Satire is a great way to neutralise opposition. When you can’t stand up and say something against something around you, it’s a great tool to do it,” Husain had noted in the interview.

Husain has taken old Urdu texts and adapted them to suit the contemporary context before. Since Husain’s performances are mostly in Urdu, and the stories he uses are not necessarily widely known, he uses asides to make the scenes clear for the audience. “When I started using these asides, it wasn’t a very conscious choice, but after a while I realised that I can use it very effectively. Then I started making a conscious choice of using these asides, I would quietly slip in an aside to present a contemporary view to the audience. I also use it as a performance trope that helps connect the audience with the performance. In watching a performance based on an unknown story, the slipping in of contemporary instances helps the audience relate to the story; suddenly it becomes about their lives,” Husain had explained in the interview with ICF. Even during this play, Husain explained the meaning of many Urdu words.

Following the pattern of Ibne Insha’s book, each “chapter” in the play ended with some questions; each of them is an astute political comment or an oblique reference to our times. For instance, one of the questions after the chapter on Akbar was, “Agar Shehzada Salim Anarkali ko le kar 12 baje raat mein aapne darwaaze ki ghanti bajaaye to aap kya karenge, honour killing ya khap panchayat?”

From the beginning, the fourth wall is broken and the audience is repeatedly addressed directly. “Bhaiya, do log kaafi hain desh mai jhoot phailaane ke liye. Aap kya isse record karke phailaayenge. Samajh rahe hain na mei kya keh raha hun?” Husain suddenly said in the middle of his performance when he spotted an audience member recording it.

The duo also touched upon the recent spate of attacks on writers and filmmakers by joking about the consequences that they might have to face for this play. “Hum koi political neta thodi na hain, jo kuch bhi kahenge aur kuch nahi hoga.” Khan joked, to which Husain replied “Haan. Hum to kalakaar hain, hum pe to khaas nazar hai”

By the end of almost 100 minutes, the audience was absolutely absorbed in the play. Suddenly, someone from the audience yelled,

“Aee! Band kar isse! Isliye thodi na aaye the yahan.”

The performers on stage seemed to have been stunned into silence. Husain seemed to regain his composure first. “Kya masla hai?” he asked. This seemed to enrage the man more and he charged towards the stage saying, “Nahi mai aa ke bata dun kya masla hai? Neta hi bana deta hun mai aa ke ruk ja!” A few members of the audience also got up, trying to intervene. “Bohat double meaning baat karoge! Ye natak kisne likha hai?” the man asked as he reached the stage. By then, both Khan and Hussain were on their feet. The man had just leapt onto the stage when Khan and Hussain took to their heels. The musicians accompanying them looked confused, unsure whether to continue their performance of Insha’s poetry or wrap up the performance. After a few seconds of tense silence, they continued.

The audience finally realised that this too was part of the performance. It didn’t take long for this also to turn into a farce. The musicians’ performance was periodically interrupted by Hussain and Khan being chased across the length of the stage by the man and two of his two cronies The farce lends some humour to this turn of events while also revealing the absurdity of such events in real life; but the few brief minutes of horror at the beginning puncture the humour and serve to remind us that this isn’t simply a laughing matter; that the violence is also very much a part of our real life.

“This is probably the most important play in the entire festival”, said Syed Raza Haider, director of Ghalib Institute. The sharp comments on the politics of our times, contemporary references that made the play relatable, and the kind of issues that it addressed is what made the play politically relevant for our time.