18 May, 2018 fell smack in the middle of the dry, draining summer that the capital is infamous for. But this didn’t deter museum enthusiasts who had gathered on the steps of India Habitat Centre’s Amphitheatre, fanning themselves as they waited for the event to begin. The Dronah Foundation had organised an event in collaboration with the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) and AUGTRAVELLER, to celebrate the International Museum Day on 18 May 2018. The event — which began with a book launch, followed by a panel discussion, — was open to the public, free of cost. It also included a two-day exhibition of glimpses from five museums: The City Palace, Udaipur; Bihar Museum, Patna; Shaheed Bhagat Singh Museum, Khatkar Kalan; Virtual Museum of Image and sound, AIIS; and Gandhi to Mahatma Museum, Gandhinagar.

Every year since 1977, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) celebrates the International Museum Day around 18 May. ICOM decides on a theme for each year, with several events and activities centred on the theme taking place around the world. This year’s theme was “Hyperconnected Museums: New approaches, new publics”.

After some delay, the event finally began with the launch of the book Museum Voices of India. Dr Alka Pande, curator of the Visual Arts Gallery at IHC and a noted Indian academician, and Vijay Garg, Vice President of the Council of Architecture, were called to unveil the book. Garg gave a brief history of how the International Museum Day came to be celebrated and why museums are important for the development of a society. Dr Pande, seeing the perspiring crowd, their discomfort only partially abated by the massive pedestal fans, kept it short, choosing to take a brief moment to thank the organisers for putting together the event.

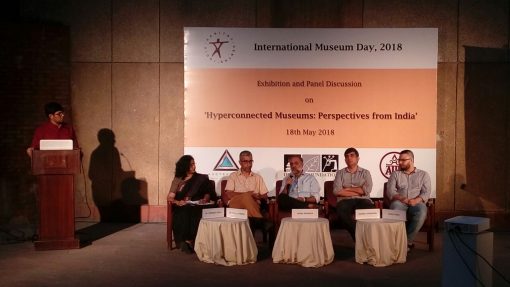

This was followed by the much-anticipated panel discussion, “Hyperconnected Museums: Perspectives from India.” The speakers of the panel discussion were “specially selected to discuss hyperconnectivty in a range of museum related areas such as accessibility, outreach, community engagement and virtual exhibits”, said Dr Shikha Jain, Director and Chairperson of the Dronah Foundation, the organisers of the event.

The moderator of the panel discussion was Sidhant Shah, a museum accessibility expert and founder of Access for ALL, an organisation that works to make museums and heritage sites accessible to the differently abled.

He began the discussion by talking about how there weren’t many heritage sites and monuments that were accessible to disabled people. He pointed out that this inaccessibility wasn’t simply because of a lack of infrastructure, which can be built, but also because of how some of these places are meant to be experienced. For instance,

museums have traditionally been largely a visual experience: there are objects and images on display, set behind glass frames, boxes and enclosures, out of reach of the visitor.

Sometimes, there might also be audio recordings that you can hear. But hardly ever are you allowed to touch the objects that are on display. This is a major drawback for those who are visually impaired; they primarily depend on their tactile and auditory senses. He outlined some of the work that Access for ALL had done to change the way these spaces are experienced.

He then went on to talk about virtual museums and how they contribute towards making museums more “accessible”. For instance, not everyone can travel to different parts of the country and visit museums in different cities, different states. Having virtual museums would allow a person to “visit” multiple museums from a single location.

Having set the purview of the discussion that was to follow, he let the speakers take over.

Dr Vandana Sinha from American Institute for Indian Studies (AIIS) opened the discussion. She began by telling the audience about how AIIS first started exploring the idea of a digital museum when they were approached by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. After many brainstorming sessions, AIIS decided that the best way to make their extensive archives available to the public, free of cost, was to create an online platform. This is how the Virtual Museum of Image and Sound, a website which can be accessed by anyone freely, came to be. Since then, the Centre of Art and Archaeology (CAA) and Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), both under AIIS, have digitised much of their archive and uploaded it online, meticulously curating the entire collection.

Manish Upadhyay, who was from AUGTRAVELLER, spoke about using technology to create an “immersive, augmented reality” of heritage sites, monuments, and other such places. AUGTRAVELLER is a mobile travel app that lets visitors “interact” with the sites they visit.

Veenu Pasricha, who set up AV Graphics, also spoke about using technology to make museum experiences better. AV graphics has, among other things, provided the technical support for setting up many modern museums and immersive exhibitions. One of these is the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Museum at Khatkar Kalan. He made a point to stress that one must remember that the end goal is to highlight the “work of art, its message”; technology shouldn’t become the focus. “If a person walks into an exhibition, he shouldn’t go, ‘Oh wow, what amazing use of technology!’ He should walk out thinking, ‘Oh wow, what a great piece of art!”

The next speaker was Kabir Punde, owner of Studio Griot, a space that uses technology to create virtual realities that allows the studio visitors to experience far-off sites as if they were at the location itself. Studio Griot had also set up the most interesting part of the exhibition, a virtual reality kiosk.

However, Surajit Sarkar’s address took a completely different route. It was the most interesting bit of the discussion by far. Sarkar, who is from the Centre for Community Knowledge, Ambedkar University Delhi, summed up what the Centre did quite succinctly when he said,

“We don’t look at books. We look at people.”

Having set out to document the history and the stories of the people of Delhi, Sarkar and his team quickly realised that a centralised museum wouldn’t suit the nature of what they were trying to do. So, the team decided to set up decentralised museums in different neighbourhoods. This is how the Shadikhampur neighbourhood museum came into existence in 2013. Shadikhampur is an old neighbourhood close to central Delhi. Sarkar recounted one of the histories that the team stumbled upon when setting up the museum. “These are the kind of stories you wouldn’t find in museums,” he noted. The team asked the people of the neighbourhood what they did when they needed new cloth or new fabric in the 1930s and 1940s. They found out that people used to get it from Raigarpura, a neighbouring village. Raigarpura was a jhuleha village, a weaver’s village, close to the Shadikhampur neighbourhood. Every household had a weaving machine. People in the village would simply weave some fabric for themselves every time they were in need of some. On being asked where they would get the cotton for it, the team was told that the people plucked the cotton straight from the semal ke perh, the cotton trees, that grew abundantly in the area.

While most of the talk had focussed on how cultural and heritage sites — take, for instance, the Red Fort, the Udaipur Palace, the Jaipur City Palace — could be made accessible to the people, Sarkar spoke about how technology could be used to document the stories of the common people of the city, of the communities, and their histories. He ended the talk saying, “Museums need to move away from the big, the monumental, and to the people who live near these structures.”