As this article is being written, the high drama that unfolded in Karnataka after the conclusion of the election in Karnataka on May 12th has come to a temporary halt. Now that all tricks played by the Governor, at the behest of the Prime Minister and Amit Shah, the national president of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), have failed, the JD(S)-Congress government will sworn in on Wednesday. But how long this coalition can survive depends not only on its internal cohesion but on other external pressures . However, the developments that took place after May 12, and also during the whole process of elections, have shown to the country how low the ruling dispensation at the Centre, the BJP, can stoop and misuse their offices. Nevertheless, in this entire episore, the credit for saving the constitutional values of this country solely lies with the three judge bench of the Supreme Court. It has not only helped restore people’s faith in the democratic process but has also in the judiciary. People’s confidence in the courts, which had dwindled after the Central government started meddling with that institution, has been restored.

The way the Governor threw open the gates to corruption by giving ample time to prove the majority to BS Yeddyurappa’s BJP, and the way Congress and JDS had to herd their flock to other states in an effort to prevent any horse trading, only shows how weak our democratic processes and institutions are . This episode, and the overall rise of right-wing forces and sentiments in the society and polity of the state, as reflected in the nature and pattern of the results, demands a deeper analysis of the people’s mandate in Karnataka. This is one such attempt.

Fractured mandate

The election for the 15th legislative assembly on 12 May has resulted in a fractured assembly by not giving adequate numbers to any party to form the government. The BJP emerged as the single biggest party with 104 seats; Congress came second with 78; and the JDS-BSP alliance third with 38 seats. The national and the political exigencies of the state compelled the Congress to declare unconditional support to JDS to form the government, an eleventh-hour attempt to prevent BJP from forming the government. Since the BJP was not in a position to make a similar alliance, the JDS alliance with Congress has come out stronger. That both these parties (JDS and Congress) had fought elections in South Karnataka to eliminate each other is now a part of history. As the possibility of horse trading became imminent, the alliance resorted to what has been called “Resort Politics,” with all the MLAs belonging to Congress and JDS were taken away to a distant resorts to keep them out of the reach of the BJP.

But, what are the factors which lead to this impasse? How did the Siddharamaiah government — which, according to almost all the pre-poll surveys held just three months before, was credited with good governance, people’s satisfaction in administration and delivery, support to welfare scheme etc, no anti-incumbency — was expected to win with a simple majority, fall short of 35 seats? How did the BJP, ridden with internal squabbles, unenviable pasts tainted with serious corruption charges and debauchery, with little to no presence in south Karnataka, accused of engineering communal disturbance in the state, accused of anti-dalit, anti-women stands exposed all over the country day by day, still double the seats won in 2013? How did the JDS which has been out of power, and not considered dependable by the minorities and dalits because it joined hands with the BJP in 2007, almost retain its seat and vote share? Why were the alternate political formations ineffective and civil society initiatives unsuccessful in generating a people’s momentum against the tide?

An analysis of the developments in run up to the elections of different parties, the focus of their campaign, and the final results throw some light on the possible reasons.

A Dominant but Declining Congress, a Growing BJP, and a Consolidated JDS

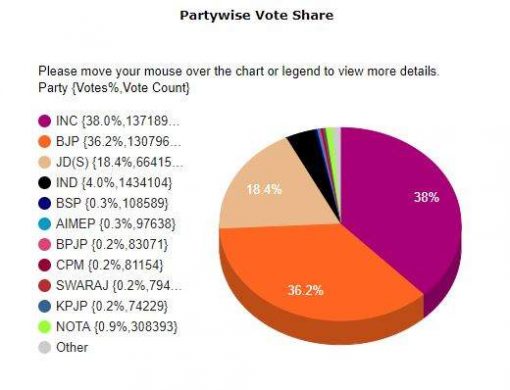

A peep into the vote share of different parties puts the outcome in some perspective. Even though the BJP is the single biggest party in terms of seats, Congress got the highest vote share at 38 percent — an increase of 1.5 percent compared to 2013.

BJP was divided in 2013. The Chief Ministerial candidate, BS Yeddyurappa, had walked out of BJP and formed his own party, the Karnataka Janata Party, during the 2013 elections. His party got 9 percent of the vote share and 6 seats. Meanwhile, BS Ramulu and the Reddy brothers had formed their own, Badavara Shramikara Raitara (BSR Congress) party and got 4 percent of the vote share and 4 seats. Put together, the BJP got 33.5 percent of the vote share in 2013.This has increased to 36.2 percent this time — an increase of almost 3%.

The JDS vote share, on the other hand, decreased by 2% — from 20.7 in 2013 to 18.3 in 2018 — with not much change in its seat share.

Thus, the Congress got the support of 1.38 crore people of Karnataka — 7 lakh more voters than BJP. Keeping this in mind, the vagaries of the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system is one of the reasons for this mismatch between people’s support and its conversion in to seats.

Historically, the BJP has never crossed the vote share of Congress in any assembly elections till date. This was true even when it obtained more seats than the Congress in 1994 (Congress– 34 seats with vote share of 26.95percent and BJP– 40 seats with vote share of 16.99 percent); or, in 2004 (Congress — 65 seats with vote share of 35.27 percent and BJP 79 seats with vote share of 28.33 percent); or in 2008 (Congress — 80 seats with vote share of 34.74 percent and BJP 110 seats with vote share of 33.86 percent).

But, is also obvious that the BJP has been steadily increasing its vote share from 4 percent in 1989 to 36 percent in 2018 .

On the other hand, the Congress has been struggling to get back to winning its vote share of a minimum 40 percent. It had declined to 34.76 percent in 2008. It has seen some improvement since 2008, with 36.55 percent in 2013 and 38 percent in 2018. Many analysts attribute this increase, among other things, to the leadership of Siddharamaiah, who joined Congress from the JDS in December 2006.

Historically, Karnataka had always been a liberal in its social values, and centrist or left of the centre in its political preference. Its mainstream was neither radically left nor fundamentally rightist. The political, cultural and literary icons of Karnataka were mainly influenced by the Lohiatite Socialism. Karnataka still preferred Congress and Devaraj Urus who initiated relatively radical land and political reforms which privileged backward castes in the political corridors and other institutions of power. His regime broke the dominance of entrenched privileges of the upper and dominant castes, comprising of Brahmins, Marhatas, Linagayats and Okkaligas.

The emergence of the Janata Party paved the way for this disgruntled social base of the erstwhile Congress party. With this emerging support base, the Janata Party defeated the Congress in 1983 for the first time. The Lingayats of North Karnataka found Ramakrishna Hegde, the helidroped Chief Minister from the High Command of the Janata Party, as their leader and supported him in a big way in 1985.

Later, the unceremonious dismissal of a highly respected Lingayats Chief Minister, Mr. Veerendra Patil, by Rajiv Gandhi in 1990 further distanced the Lingayats from the Congress. It lost its seat of power in 1994 against Janata Dal when Mr. Deve Gowda, the most revered leader of Okkaliga, joined with the Lingayats under the banner of Janata Dal (JD) to defeat the Congress. This development decimated the Congress in subsequent elections.They were reduced to 35 seats. The BJP also vied for the political space that this opened up and garnered 17 percent of the vote share and 44 seats and became major opposition party in the house. In 1999, the Janata Dal was split into two parts Janata Dal (Secular) and Janata Dal (United) at the national level. In Karnataka Janata Dal (Secular) was seen as the party of Okkaligas and hence, most of the Lingayats base was divided between JDU and BJP. Since the BJP was in ascendance in the national politics also, the Lingayats slowly consolidated under the BJP.

On the other hand, the Okkaligas, concentrated in the southern Karnataka, were consolidated under the JDS. It could also managed to establish a good support base among the Muslims and a section of dalits. The vote share of JDS hovers around 18-20 percent with 30-40 seats. Only in 2004 did it rise to 58.

In a nut shell, the Congress was reduced to a party of predominantly AHINDA (the Kannada acronym for minorities, backward castes, and dalits) social base with declining, although continuing, support of a section of Lingayats from North Karnataka and the support of Okkaligas from some pockets of South Karnataka.

Hence, after 2000, all three major parties were trying to increase their support base by making attempts to include other social segments.

An analysis of the results of 2018 assembly election from these vantage points seems to be more useful to get hints for the future developments.

Whom did the higher vote share help?

The 2018 election witnessed the highest voter turnout in the electoral history of Karnataka at 72.3 percent turnout — an increase of 1.1 percent compared to the second highest in 2013. In some district and constituencies, the voting percentage was as high as 89 percent, registering an increase of 5 to 7% increase in the rural constituencies of old Mysore and Mumbai Karnataka. Since there was no wave of anti-incumbency and voter satisfaction was high with the chief minister among Muslims, backward castes and dalits, it was expected that more voters from these communities would have voted and hence would have benefitted the Congress. But the results present a complex picture.

In 2013, the BJP parivar together had polled 32.37 percent of the votes. By the BJP parivar I mean Yeddyurappa, who had formed his own party the KJP, and Sriramulu and mine barons who had formed their own BSR Congress Party. This time the United BJP polled 36.2 percent. Compared to 2013, this means an additional 30 lakh voters voted for the BJP.

The Congress had polled 36.59 percent in 2013. In 2018, the Congress garnered the support of 38 percent voters. Compared to 2013, this means an additional 24 lakh voters have voted for the Congress.

The JDS, on the other hand, had got 63.39 lakhs votes in 2013. Though its vote share decreased from 20.7 percent to 18.4, three lakh more voters voted for the JDS this time.

Thus, even though Congress got the highest votes, BJP’s rate of improvement was more than the Congress. While the Congress vote share has spread across the region, the votes polled for the JDS and BJP was focussed and hence resulted in more seats.

That apart, an analysis of AHINDA votes can also provide the pattern of voting. The top ten Muslim dominated constituencies had usually retained either Congress or JDS candidates. This time all the winning candidates from those seats have bagged additional 16000-45000 votes. But in two of these ten constituencies, Belgaum North and Bijapur city has gone to the BJP. Even though the Congress candidates here got 15000 more votes, the winning BJP candidate from Belgaum North, for example, has got 61000 more votes than in the 2013 elections.

This trend suggests a possible counter polarisation against AHINDA votes of Congress in AHINDA dominated constituencies.