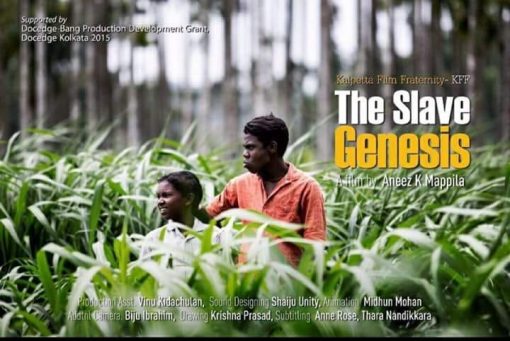

Malayalam documentary filmaker Aneez K Mappila won the National Film Award for the Best Anthropological Documentary Film in 65th National Awards, Government of India for his documentary The Slave Genesis. The Indian Cultural Forum talked to the director on his experience while working with the Paniya tribes.

Sreelakshmi (SL): As a person not belonging to the Paniya community, did you feel like an outsider while working with the Paniyas?

Aneez K Mappila (AM): My family has been living in Wayanad for the past two generations. We’ve always lived with the Paniyas. I’ve never felt like an outsider among the Paniyas. I begin the documentary with recollections from my life, everyday scenes in the Paniya community. The district, Wayanad, is mostly inhabited by migrants who’ve come and settled here. Paniyas, the aboriginals, work in these migrants’ houses and lands as domestic helpers; they work in their rice fields, coffee plantations, pepper gardens, spice gardens, things like that. The world is oblivious of their existence; the public is unaware of their labour, their contributions, their plight. Currently, they work as bonded labourers in Wayanad, where they have lived for generations. This is because these lands are now owned and controlled by the migrant settlers. The Paniyas lament that they’ve been reduced to slaves by the migrant settlers. Through the documentary, The Slave Genesis, I also wanted to show how this affects the Paniyas and their own sense of self. For me, the Paniyas are not strangers. I have lived my whole life with them. I wanted the world to get a sense of the Paniya community primarily through visuals. I may have got the National Film Award in the Best Anthropological Documentary Film category, but I don’t want the film to be seen only as an anthropological film. I know that is how many people perceive it.

SL: Why did you choose monologues in your documentary, The Slave Genesis?

AM: The Slave Genesis is a documentary without narration. The film is further divided into chapters. It begins with some scenes from my childhood, with a voiceover of my narration. This section of the documentary has some monologues, most of which show the Paniyas bemoaning their condition in society. As the film progresses, the monologues fade away and it is only through visuals that the Paniyas’ life is revealed. I wanted the audience to interpret the film primarily through these, and not through dialogues. There are hardly any dialogues. In fact, even the monologues only make up about 20% of the film.

SL: It took three and a half years for you to complete the documentary. How did you overcome the technical difficulties of making a film without a crew? Did you receive any help or funds for the documentary?

AM: At the beginning, it was difficult for me to shoot the documentary. I couldn’t even afford to rent a camera or a technical crew for shooting it. In fact, Wayanad doesn’t have facilities, which some of the other districts do. Usually, I would take my camera and go to the fields in the morning. Besides, I wanted to show that a documentary can be shot without a supporting technical crew. Only in certain sections of the film, where I had to be in front of the camera, were shot by a friend of mine, Biju Ibrahim. I also got some technical help for sound mixing. Apart from these two, everything else, from handling the camera, to editing, and sound recording, I did by myself.

Some of us in Wayanad had started a film society, Kalpetta Film Fraternity (KFF) a couple of years back. It runs on crowd funding. I’ve credited KFF as the co-producers of the documentary. About three years back, Docedge – a Kolkata-based pitching forum, and Bang productions, a Singapore-based production house, gave me a grant worth Rs.2000 to begin the work on my documentary. See, documentary making is my source of livelihood. I make short films on the forests, the flora and fauna of Wayanad, for multiple NGOs. I have been working in this field for quite some time. Before this, I’d never felt the need for an external producer. In fact, it was only later, when the overall cost of production became higher than expected, that KFF stepped in as co-producers to help me out.

SL: You went through books such as Keralathinte Africa, written by K Panoor, and the texts written by British museologist Edgar Thurston. How did these books help you in the documentary?

AM: Yes, I did go through these books. But I didn’t let my research end with them. These books were written by people who hadn’t spent much time with the Paniyas. They were from an outsiders’ point of view. The reality is very different. I made the documentary from my personal experience. For instance, the story in The Slave Genesis is revealed through penapattu, a post-death ritual song for the Paniya community. So far, penapattu has not been documented by any of these researchers. Edagar Thurston’s book was published in 1907. He lived in an estate at Methady for six months and studied the tribes. His work provides, at best, a broad overview of the Paniyas. For instance, he mentions their appearance, dressing patterns, etc. Similarly, Rao Bahadur, a former Deputy Collector of Wayanad, Gopalakrishnan, and others have studied the Paniyas but they all did an anthropological study. Most people were interested in studying their historical background, appearance, their social status, and such. A century has passed since these books were written. More recently, K Panoor did some research on the Paniyas, but even that was some forty years back. The present situation of the Paniyas is not the same anymore. I have tried to show this, the current reality of the Paniyas living in Wayanad.

SL: Wayanad district has the highest tribal population in Kerala. Most of these tribes face intense poverty and have high mortality rates. Out of all the tribes in Wayanad, why did you choose to focus on the Paniyas?

AM: Wayanad district has a number of tribals like the Paniya, the Kurichiya, the Adiyar, the Kurumar, the Kattunaiyikar, among others. Kurichiya, Kattunaiyikar, and Kurumar tribes are usually dependent on agriculture; they own the land that they work on. While some of them do face poverty, they’re a little better off than the Paniyas because they are not landless. It is also true that, in some of these tribes, the adult mortality rate is very high. Out of these, the Paniya is the largest tribe. They have no permanent place of settlement, and their landlessness makes their exloitation easier. Their poverty has forced them into slavery. In Malayalam, pani means work and Paniyar refers to people who work. Paniyas can be seen in every Panchayat constituency of Wayanad. The other tribes are concentrated in only some constituencies like Mananthavady, Meenangadi, and Thirunelli. Among all the tribes in Wayanad, Paniyas are the worst off when it comes to poverty and slavery. Moreover, they have been completely invisibilised.