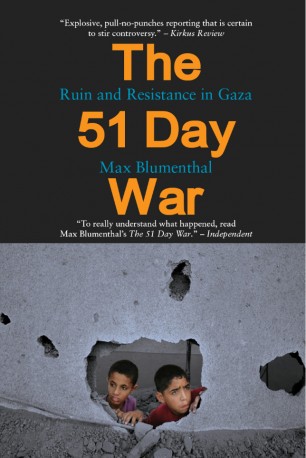

The visuals of Israeli snipers cheering as shots are fired against unarmed protesters in Gaza, who are participating in The Great March of Return, have gone viral on social media. We think it is important to remember that Gaza is an open air prison and that these cold blooded murders of unarmed residents, who are mostly refugees, has been Gaza’s reality since 2004. Here, we publish an excerpt from Max Blumenthal’s book, The 51 Day War (LeftWord, 2015), on the 2014 siege of Gaza. The excerpt is from the chapter “A Thin Red Line” that demonstrates how arbitrarily the Israeli military targets innocent Palestinians.

As the day of August 14 wore on in the ruins of eastern Shujaiya, I began to sense that I was inside a vast crime scene. Dan Cohen, Ebaa Rezeq, and I visited almost a dozen homes occupied by Israeli soldiers in Shujaiya, wading through rubble and piles of shattered furniture in search of clues into the Israeli plan of operation. I found floors littered with bullet casings, sandbags used as foundations for heavy machine guns, sniper holes punched into walls just inches above floors, and piles of empty Israeli snack food containers.

In the stairwell at the entrance to one home we visited, soldiers had engraved yet another Star of David — we would find these in vandalized Palestinian homes across Gaza’s border areas. In a nearby house, soldiers used markers to scrawl in mangled Arabic, “We did not want to enter Gaza but terrorist Hamas made us enter. Damn terrorist Hamas and their supporters.” A wall in another home had been vandalized with the symbol of Beitar Jerusalem, the Jerusalem-based football club popular among the hardcore cadres of Israel’s right-wing.

Below the Beitar logo was the slogan, “Price Tag.” The phrase refers to the price settlers seek to exact on the native population of the occupied West Bank each time one of their illegal outposts is demolished or a settler is attacked by Palestinians.

Over the past decade, the attacks have grown in frequency and spread into Arab neighborhoods in core Israeli cities, with racist graffiti appearing on Palestinian Christian churches and businesses. The appearance of price tag–style vandalism during the war in Gaza coincided with a 45-percent plunge in price tag attacks against Palestinians in the West Bank, leading an Israeli army official to speculate that “solidarity with the [army]” had provided an outlet for the violent impulses of Jewish fanatics.In each home the soldiers had occupied, we found crude maps of the immediate vicinity etched on the walls. Each house was assigned a number, possibly to enable commanders to call in air and artillery strikes ahead of their forward positions. Names of soldiers were listed on several walls, but were mostly covered with spray-paint upon the troops’ departure. I learned later through several Israeli friends who had served in combat units that these were shooting schedules that determined who would be on sniper duty and when.

In the ruins of a second-floor bedroom, in an empty ammo box under a tattered bed, a group of young local men had discovered two laminated maps of Shujaiya. They eagerly handed them over to me, hoping that I would be able to make sense of them.

I was immediately able to determine that the maps were photographed by satellite at 10:32 a.m. on July 17, just days before the neighborhood was flattened. The date in the upper-right-hand corner of one map was written American-style, with the month before the day, raising the question of whether it was a US or Israeli satellite that had captured the image.

(The US National Security Agency has routinely shared information with Israel’s Unit 8200, a cyberwarfare and surveillance division embedded within military intelligence, according to journalist James Bamford writing for the New York Times.) Outlined in orange was a row of homes numbered between 16 and 29; the homes immediately to their west were labeled with arrows indicating forward troop movements.

A local man who had accompanied us into the house pointedat the homes on the map outlined in orange, then motioned out the window to where they once stood. Every single house in that row had been obliterated by airstrikes. I looked back at the map and noticed that the dusty field we faced was labeled in Hebrew, “Soccer Field.” Devised at least two days before the assault as an apparent guide for invading soldiers, the map sectioned Shujaiya into various areas of operation, with color-coded delineations that were difficult to decipher.

After the war, Eran Efrati, a former Israeli combat soldier turned anti-occupation activist, interviewed several soldiers who participated in the assault on Shujaiya. “I can report that the official command that was handed down to the soldiers in Shujaiya was to capture Palestinian homes as outposts,”

Efrati wrote on his Facebook page. “From these posts, the soldiers drew an imaginary red line, and amongst themselves decided to shoot to death anyone who crosses it. Anyone crossing the line was defined as a threat to their outposts, and was thus deemed a legitimate target. This was the official reasoning inside the units.”

Months later, when we met in Brussels to present testimony on Israeli war crimes in Gaza at the Russell Tribunal, Efrati helped me decipher the map I found. He pointed me to a red line drawn on the map that bisected Shujaiya from east to west. It was labeled in Hebrew as “Hardufim,” or “Dead People.” Efrati explained that while the term “Hardufim” was often called out through Israeli army radios when a soldier was killed and required transport from the theater of battle, the word was also used to mark free-fire zones in the Gaza Strip where soldiers could kill people regardless of their involvement in battle.Efrati was a veteran of Operation Cast Lead in Gaza in 2008–09 and had personally witnessed the delivery of this order. In the area occupied by Israeli soldiers around the red “Hardufim” line, the killing that had previously taken place by air and distant artillery assaults took on agruesomely intimat equality. It was there, in the ruins of their homes, that I met with returning locals who survived what they described as a spree of cold blooded executions by Israeli soldiers.

The Killing Fields

That day in mid-August, at the eastern edge of the “Soccer Field” now occupied by tents and surrounded by demolished five-story apartment complexes, I encountered a middle-aged man wearing an eye-patch. Introducing himself as Mohammed Fathi Al Areer, he led Dan, Ebaa, and me through the first floor of his home, which was now little more than a cave furnished with a single sofa, then into what used to be his backyard, where the interior of his bedroom had been exposed by a tank shell. It was here, Al Areer told me, that four of his brothers were executed. One of them, Hassan Al Areer, was mentally disabled and likely had little idea he was about to be killed. Mohammed Al Areer said he found bullet casings next to the victims’ heads when he discovered their decomposing bodies days later. Just next door lived the Shamaly family, one of the hardest hit clans from Shujaiya. Hesham Shamaly, twenty-five, described to me what happened when five members of his family decided to stay in their home to guard the thousands of dollars of clothing and linens they planned to sell through their family business. When soldiers approached the home with weapons drawn, Shamaly said his father, Nasser, emerged with his hands up and attempted to address them in Hebrew.

“He couldn’t even finish a sentence before they shot him,” Shamaly told me. “He was only injured and fainted, but they thought he was dead so they left him there and moved on to the others. They shot the rest—my uncle, my uncle’s wife, and my two cousins—they shot them dead.”

Miraculously, Shamaly’s father, Nasser, managed to revive himself after laying bleeding for several hours. He walked on his own strength toward Gaza City and found medical help. “Someone called me to tell me he was alive,” Shamaly said, “and I thought it was a joke.” In December 2014, Dan Cohen located Nasser Shamaly, who recalled for him how he managed to escape the shooting gallery of Shujaiya by navigating through his neighbors’ destroyed homes, flagging a taxi, and finding medical treatment at Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City. He confirmed that he had been shot in the left arm while addressing the Israeli soldiers in Hebrew, and added that his family had no idea he was alive until he phoned them from the hospital.On July 20,

Hesham’s twenty-three-year-old cousin Salem Shamaly returned to his neighborhood at 3:30 p.m. during the temporary ceasefire to search for missing family members alongside members of the International Solidarity Movement (ISM). At the time, Salem’s parents had no idea he was in the neighbourhood.

As Salem waded into a pile of rubble wearing jeans and a green t-shirt with the ISM volunteers just meters away, who were clad in neon-green vests identifying them as rescue personnel, a single shot rang out from a nearby sniper, causing his body to crumple to the ground. As Salem attempted to get up, another shot struck him in the chest. A third shot left his body completely limp. Apparently, he had crossed the red free-fire line.

The incident was captured on camera by a staffer at Gaza’s media ministry named Mohammed Abdullah. As international broadcast news outlets reported on the startling execution, Israeli military spokespeople were strangely silent. Back in Gaza City, where survivors of the Shamaly family had taken shelter in a relative’s apartment, Salem Shamaly’s sister and cousinreceived the link to the video in an email from a friend. In the course of three minutes, they watched Salem die. They knew it was him because they recognized the sound of his voice as he cried out for help.