The films directed by Sergei Eisenstein during the 1920s marked a new paradigm in the world of cinema. A pioneer in the practice of montage, he was among the early major theorists of cinema.

Born on 22 January 1898, Eisenstein left behind a rich legacy that is complex and in many ways, immeasurable. The power of his movies was such that the UK authorities imposed a ban on his 1925 film Battleship Potemkin until 1954.

Film montage is an editing technique that pieces together a series of frames to form a continuous sequence that is used at several defining moments in films – memorable examples of montage sequences in films of the recent decades include those in The Godfather (1972), and The Karate Kid (1984).

The montage effect was first demonstrated by film theorist and director Lev Kuleshov, and was refined by Eisenstein in his films such as Battleship Potemkin.

Born in Latvia, young Eisenstein started off in the footsteps of his father and took up architecture and engineering. He joined the Red Army in 1918 to serve the Bolshevik Revolution.

During this time, he developed an interest in theatre and started working as a designer for theatre doyen Vsevolod Meyerhold in Moscow. He made his first film Glumov’s Diary in 1923.

Eisenstein's films are unflinchingly political, and they galvanised the cinema of the former Soviet Union and beyond with their bold narrative approach, stylistic flourishes, dramatic use of cinematography, editing and music, and marriage between the socialist worldview and the craft of filmmaking.

Strike (1925), Eisenstein’s first full-length feature film, depicts a workers’ strike at a factory in pre-revolutionary Russia in 1903.

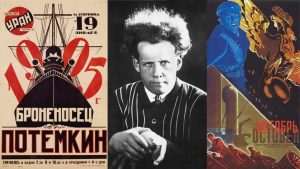

Battleship Potemkin , also released in 1925, narrates, in dramatised fashion, the rebellion of the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin against their offices in June 1905, in the midst of the 1905 Russian Revolution. The film brought worldwide critical acclaim to the director, and contains one of the most famous scenes in the history of world cinema – the Odessa Steps sequence which depict the massacre of civilians by the Tsar's soldiers and Cossacks at the eponymous steps. This classic scene is considered one of the most influential montages in film history. See it below:

October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928) is a dramatised re-enactment of the events leading up from the 1917 February Revolution to the October Revolution that year. The film was commissioned by the Soviet government to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution.

Eisenstein’s other notable films include ¡Que viva México! (1930, released in 1979), Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan The Terrible (in two parts, released in 1944 and 1958 respectively).

“The revolution gave me the most precious thing in life – it made an artist out of me. If it had not been for the revolution I would never have broken the tradition, handed down from father to son, of becoming an engineer,” wrote Eisenstein about the impact of the 1917 Russian Revolution on his life.

“The revolution introduced me to art, and art, in its own turn, brought me to the revolution.”

He was only 50 when he died following a heart attack on 11 February 1948.

Eisenstein has been lauded as one of the "effulgent lodestars" of world cinema hailing from the Soviet Union, along with Dziga Vertov, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Andrei Tarkovsky.

Eisenstein’s legacy endures, not only in the techniques of filmmaking he pioneered, but also in the political approach he brought to filmmaking. His ideas strongly resonated among students of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, during their agitation against the appointment of Gajendra Chauhan as Chairman of the Institute in 2015 – one of their slogans was “Eisenstein, Pudovkin, we shall fight, we shall win!”

(with inputs from IANS)