Dalits started to appear as significant players in the colonial public sphere after 1900, and Kusuma Dharmanna stands out as one of the first to challenge the brand of nationalism advocated by caste Hindus. In rejoinder to a popular Brahman nationalist Garimella Satyanarayana, who preached swarajya (independence) and wrote songs rejecting British rule such as as Makodhu Ee Thella Dhorathanamu (We do not want this white landlordism), Dharmanna asked, “What is Swarajya?” and wrote Makodhu Ee Nalla Dhorathanamu (We do not want this black landlordism).

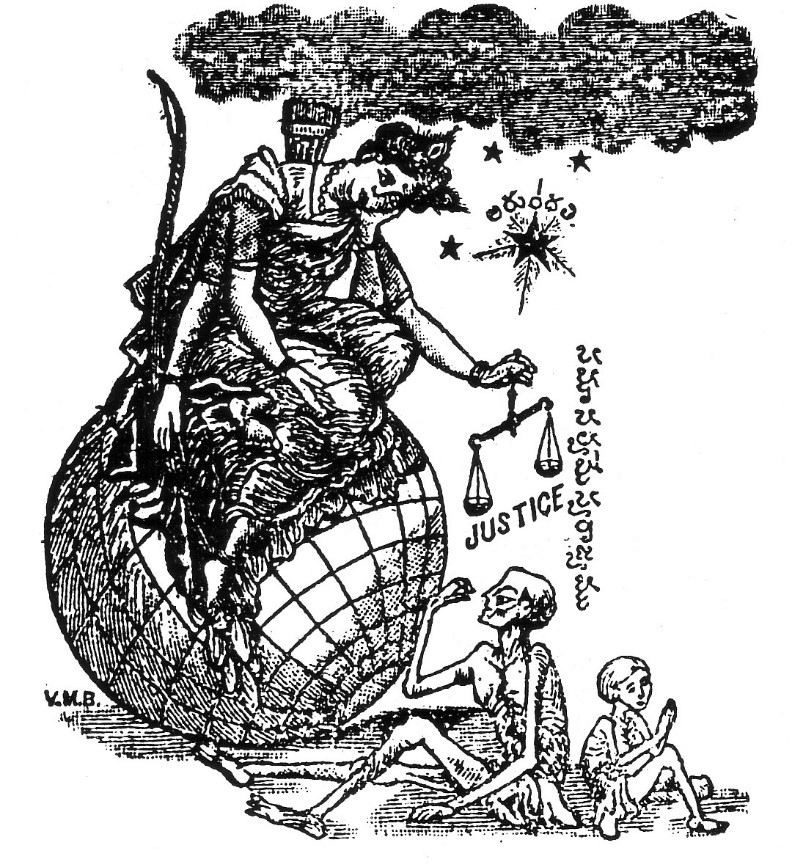

He criticised caste Hindus: “In the name of Swarajya they organise meetings! Always praise Gandhi, preach Hindu–Muslim unity and advocate wearing Khaddar . They claim peace as Swarajya and organise peace volunteers! But they bury our issues.” He also criticised those caste Hindus who advocated independence from the British, but refused the same liberty to untouchables: “They fight with government asking for independence but they refuse to give independence to Malas. They do not allow us into temples and public places. Also they do not allow us to take water from wells! They say Malas do not have rights. If we do not have rights, how can they have Swarajya?” Dharmanna asked his brethren to wake up and claim their birthright: “Born as humans, why should we lead a life of slaves? There is no sin in losing life in defending our rights. Come forward and claim your birthright.” He also wrote songs for Dalit women, urging them to end their slavery and claim social equality. Through his powerful songs, Dharmanna advocated equality and liberation for Dalits as a pre-condition for independence (see Figure below).

Mother India | Source: Title page of Kusuma Dharmanna’s Nalladoratanamu (Rajahmundry, 1923 | Note : In this powerful and popular iconic image, which represents untouchables) and in another, she holds the scales of justice which are not levelled,indicating inequality; next to it are the words, Swarajyame Samanathwamumdash: Equality is Independence. The luminous star in the sky is Arundhati, associated with Madigaidentity (Madigas are referred to as Arundhatiyas because Arundhati is said to be a Madiga girl who married the Brahmin sage Vashishta). This illustration was printed on the title page of Dharmannars’s ‘Harijanashathakamu’ (1933). Jala Rangaswamy also used it on the title page of ‘Antarenivarevaru’ (Rajahmundry, 1930).

Much more radical was Vagiri Amosu who protested against the Gandhi-led civil disobedience movement of 1930 and viewed it as an effort to maintain caste Hindu domination over the deprived classes. To illustrate his argument, Amosu pointed out the intolerant attitude of caste Hindus: “If they spot an Adi-Andhra in a temple, they react angrily like a snake, which fumes when you step on its tail, and beat him to death. But they honour a dog as god! This sort of incident is reported every day in newspapers.” He expressed doubt over the possibility of social equality and about untouchables having a share in the governance of the country in an independent India:

They [caste Hindus] have no ethical principle of respecting a fellow human being. We have no guarantee that we will get respect in future from such unkind people. There are many educated people among our community, how many of them will have a chance to govern the country along with caste Hindus as equals? The national movement will not off anything for the deprived like us except wishful thinking.

Amosu did not trust the integrity of so-called nationalist leaders and exposed their selfishness and indifference towards the suff erings of untouchables at their hands: “People who have no interest in social welfare are contesting as MLAs and MLCs and spending thousands of rupees and begging for votes in the untouchable streets. They do not even pay wages to the labourers who toil in their fields. How will they serve this nation?” Amosu completely rejected the national movement, viewing it as a vehicle for caste Hindus to increase their power. However, his critique, as did Dharmanna’s, did include important elements such as the demand for social equality and the ending of economic exploitation of untouchables.