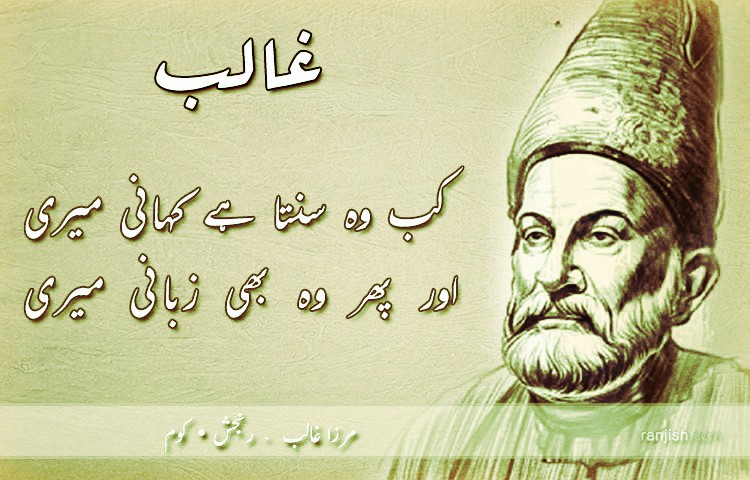

On the occasion of Ghalib’s 220th birth anniversary, Indian Cultural Forum brings to you an extract from the chapter, “Buddhist Thought and Shunyata”, from the book Ghalib: Innovative Meanings and the Ingenious Mind, by Gopi Chand Narang, translated into English by Surinder Deol, and published by Oxford University Press.

Sufi saints, bhaktas, and aulias have been using the language of silence or the language of unsaying for centuries to share with their followers the inner truth that they could not express in the normal worn-out conventional language. The Bhakti movement started in the sixth to seventh centuries with the Adyar and Alwar poets of the present-day Tamil Nadu region. The movement gained momentum during the tenth century in Karnataka and in the twelfth century in Maharashtra. From the fourteenth century through the sixteenth century, the mystical poetry associated with the movement had spread like wildfire into most regional and local languages of the entire northern India.

From Bedil, the path to Ghalib is pretty discernable. But Bedil is a transcendental Sufi poet, while Ghalib is a worldly poet whose main concern is the condition of a human being.

The cultural interaction and popularity of Sufi ideas strengthened the trend. Spiritually enlightened Sufi seerpoets like Kabir, Bulleh Shah, Shah Husain, Guru Nanak, Waris Shah, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Jay Deva, and Tukaram brought popularity that most poets had never dreamt of. In addition, there were local poets who carried the message of Bhakti and Sufism everywhere to villages and homes. You could not find anyone living during this time who had not been influenced by the poetry of these saints and their disciples. The Persian poetry associated with Sabke Hindi tradition that flourished between the thirteenth and the nineteenth centuries could not have kept aloof from these extremely popular writings in local languages like Braj, Khari Boli, Awadhi, Rajasthani, Bhojpuri, Maithli, Maghdi, Saraiki, Punjabi, and so on. Among these poets, Kabir was someone special because he combined in his work ideas of Sufism and Nirguna Bhakti, and he was probably one of the greatest folk poets of all times.

In order to help ordinary people, who had their mirror of consciousness rusted in the routine and humdrum of day-to-day life, there were experiments in Sanskrit and other local languages, using innovative methods and involving different forms of negative dialectics for centuries, and these were an integral part of the ancient Indian civilization. The use of folk idioms, magic, puzzles, and paradoxes for this purpose was prevalent for centuries and examples of these are found in the Upanishads, Puranic tales, and Mahabharata. In the epic story of Mahabharata, when the five Pandu brothers during the time of their exile go to a pond to quench their thirst, they are confronted by a hidden (mystical and magical) voice that asks them some paradoxical questions. Four brothers die as they cannot provide the correct answers. It is the eldest brother who, by using his innate intelligence, offers correct answers and thus revives the four dead brothers after which they all had water to drink to their heart’s content. Such examples are found in other traditions as well. In Amir Khusrau’s Hindavi and Persian poetry and later masnavis, we find abundance of riddles, puzzles, and magical tales, the purpose of which was to ignite interest among common folks to think about and reflect on the mystery of existence.

Kabir’s time is nearly a century after Amir Khusrau. He not only wrote songs like any other poet but also experimented in writing poetry that did not fit into any of the known genres, or sometime did not even make any sense to the reader at the first look. The language used in this form of poetry has been called ‘upside-down language’, ulat bamsi, because of the dialectical twist, whose sole purpose was to create a shock effect on the reader or the listener. Through the simple act of poetic provocation, the listener was prompted to ask questions and enter into a deeper dialogue. Because the language used novel signifiers and phrases, it is also called ‘twilight language’ (Doniger 2011: xiv). Dim-lit language, topsy turvy language, abstract language, and paradoxical language are different forms of the same problem. Such modes were common in local folk traditions. With the evolution of ghazal as a popular genre in Sabke Hindi poetry, it is not improbable that these indigenous modes in some form permeated into the sophisticated style of the Persian masters. The indigenous genres of kabits, sakhis, sorthas, and especially the two-lined dohas were not very distant from the twolined couplets of the ghazal. The ghazal had travelled to scores of lands with the advent of Islam in the medieval times but nowhere did it gain such popularity, strike such deep roots in the local soil, and synthesize with the poetic traditions of local languages as it did in India. Such cultural questions have not yet been fully addressed by Persian scholars. Nowhere is the genre of ghazal so soaked in the indigenous poetic traditions as it has been in India. Bedil is at a much higher pedestal in terms of the use of sophisticated literary language compared to Kabir but they share many common existential and poetic concerns. Both are different in many respects but Bedil’s imagination is as much on fire as Kabir’s to unravel the mystery of the existence and the predicament of humankind. The density and paradoxical complexity of Bedil’s poetics cannot be fully appreciated unless the cultural synthesis at work at that time is comprehensively understood. Both of them were passionate about spreading the message of love and mitigating the suffering of the common folks.

From Bedil, the path to Ghalib is pretty discernable. But Bedil is a transcendental Sufi poet, while Ghalib is a worldly poet whose main concern is the condition of a human being. In Ghalib we find that mysticism and transcendentalism of the saint-poets mesh into an existential poetic concern of its own kind. He is caught between the joys and sorrows of life while facing the challenges of living in a mysterious world abandoned by its Creator. This is the place where Ghalib’s voice consciously or unconsciously is at home using the archetypal negative dynamics found in the ancient Indian and Buddhist traditions about which we talked earlier in this chapter.

In order to illustrate the point regarding Kabir’s upside-down folk poetics, we present here some excerpts from his writings. It is futile to look for any urban sophistication as we find in Bedil or Ghalib but one can certainly feel the touch of the artistry of folk, the warmth of rural idiom, along with the whiff and smell of the soiled earth that is at the very centre of this kind of poetry, though one can also feel the dialectical innovative pull of the pulsating quest which tries to be in communion with the mystery of existence:

1. O learned one,

tell me how I became a woman from a man.

I was neither someone’s wife, nor a virgin,

Never pregnant, yet I deliver kids;

I am the mother of many.

I have not spared a single unmarried man,

yet I am still a virgin.

In a Brahman’s house I am his wife,

but in a Yogi’s I am a disciple.

After reading the Koran,

I walk like a Muslim woman.

I do not belong to my parents or to my in-laws.

I do not allow any man to touch me.

Kabir says I will live long.

I am the one who is untouched. (Kabir 1961: 160)

2. I am neither a believer, nor a non-believer.

I am neither an ascetic, nor a temple worker.

I do not say anything; I do not hear anything.

I am neither serving anyone, nor being served.

I am neither bound, nor completely free.

I am neither separate from others, nor I am with anyone.

Neither bound for hell nor heaven.

I have indulged in every act, yet I am detached.

This is understood

only by the one who is perceptive.

Kabir does not cheer lead

any one established belief system,

nor does he trash any particular one. (Kabir, quoted from Narang

2005: 223)