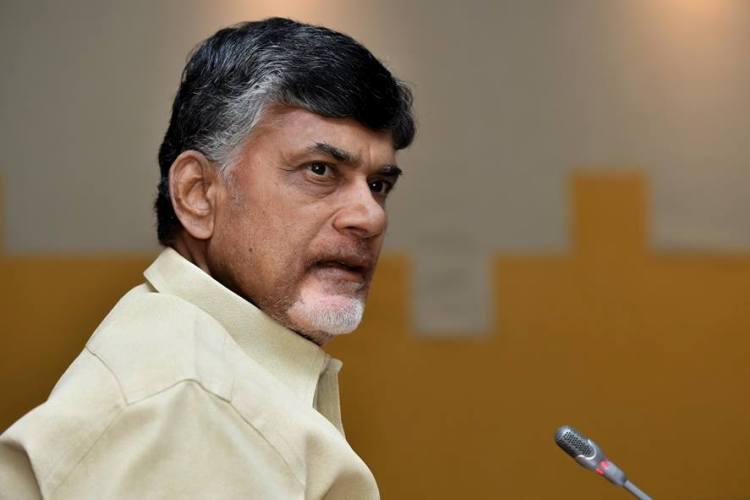

Amid fast changing developments, the Andhra Pradesh Legislature passed a bill into an Act which confers 5% reservations to the Kapu community. At nearly 22% of the population, it is an electorally significant community. A few days before that, Telugu Desam Party (TDP) supremo, Chandrababu Naidu, issued a warning to the BJP on the Polavaram Project. A week before that, he had announced on the floor of the assembly that the Andhra Pradesh government would commit to building 20 lack units of houses for the poor and downtrodden, provided that the Central Government came forward to fund the project generously. All three decisions, taken in a row, raised eyebrows among the political analysts in the state and at the Centre.

For instance, consider the issue of Kapu reservations and the political context in which the decision has been taken. What makes it even more suspect is the speed with which it was passed, violating the basic constitutional modalities and well established judicial precedents. In his efforts to win over the Kapu community, the TDP supremo willfully defied the basic principles of governance. He did not wait for the proper submission of the commission report, which he had appointed himself. Instead, he took the decision on the basis of individual feelings and opinions of the members of the commission, neither of which has any legal sanctity in the eyes of the law.

The demand for reservations for the Kapu community is a contentious issue in the political landscape of Andhra Pradesh. This demand is about a quarter of a century old, since it was raised for the first time in 1993. Up until then, Vangaveeti Mohana Ranga Rao (V M Ranga Rao) used to be the sole representative of this community’s interests, before he was killed in a gang war. Up until then, the Kapu people had been staunch Congress supporters. However, after Mudragada Padmanabham, a seasoned politician, jumped into the vacuum created by the sudden demise of V M Ranga Rao, the Kapu community shifted its political allegiance to the TDP.

In 1993, for the first time, the TDP extended its support to the demands of the Kapu community, including their demand for reservations. Satisfied with this reassurance, the Kapus played an important role in bringing TDP back to power in the 1994 elections. They also played a very crucial role in TDP’s usurpation of power from the Congress. On both the occasions, the TDP played its cards well and arrived at a compromise with the community leaders. In return, the Kapus played a key role in shifting droves of voters to the TDP camp in the East and West Godavari districts, regions where this community is the traditionally dominant caste, both in terms of land holdings and commanding the social and political institutions of power.

After coming back to power in 2014 with the support of the Kapu community, the TDP pushed the issue of the Kapu reservations under the carpet, just as they had done in 1994, angering the community. After three years of overt and covert compromises with the Kapu community, in September 2015, the Andhra Pradesh state government issued Government Order (Manuscript Series) No 5, which says, “It has been felt that Kapu, Balija, Telagana, and Ontari Communities in the state are socially, educationally, and economically in a backward condition, [in comparison with] the other forward castes…” They also formed the Kapu Corporation with an aim of extending financial assistance, subsidy, and other endowments to the Kapu community. The Kapu community is not otherwise eligible for such an intervention from the state, because, according to the constitutional mandate, the state is expected to support the development and advancement of socially, economically, and educationally backward communities, as recognised by the constitution. The Kapu community does not fall in this category. By the date of issuance of the said Government Order, neither did government have any authentic information about the backwardness of the Kapu community, nor had it appointed a commission to ascertain the gravity of the backwardness. For this reason itself, the said Government Order is a violation of the constitutional mandate laid down by the Supreme Court in 1966 in the P Sagar vsState of Andhra Pradesh case. This was reaffirmed and consolidated in the famous Indira Sawhney case.

In Government Order (MS) No 16 in 2016, May, the state government unveiled an economic assistance scheme for the advancement of the Kapu community with cinemascope dimensions. According to this Government Order, the state government earmarked Rs.1000 crore for the economic assistance program aimed at the economic advancement of people belonging to the Kapu community. Granted, a government does have the authority to initiate affirmative action within the limits of the constitutional mandate. But no government has the authority to assume that a particular community is backward in its economic and educational entitlements “when compared to other forwards communities”. The terminology of GO (MS) No 5 itself is void under law. But the TDP government has never cared for any constitutional propriety when it comes to ensuring its political fortunes.

Though it is a little lengthy, the recent Supreme Court observations need to be quoted in full paragraph. In Ram Singh & Others vs Union of India, the Supreme Court stated clearly that the self proclaimed backwardness or forwardness of a community cannot be the basis for any administrative action. The Apex court said:

54. The perception of a self-proclaimed socially backward class of citizens or even the perception of the “advanced classes” as to the social status of the “less fortunates” cannot continue to be a constitutionally permissible yardstick for determination of backwardness, both in the context of Articles 15(4) and 16(4) of the Constitution. Neither can any longer backwardness be a matter of determination on the basis of mathematical formulae evolved by taking into account social, economic and educational indicators. Determination of backwardness must also cease to be relative; possible wrong inclusions cannot be the basis for further inclusions but the gates would be opened only to permit entry of the most distressed. Any other inclusion would be a serious abdication of the constitutional duty of the State. Judged by the aforesaid standards we must hold that inclusion of the politically organized classes (such as Jats) in the list of backward classes mainly, if not solely, on the basis that on same parameters other groups who have fared better have been so included cannot be affirmed.

This is in line with the judicial pronouncement of the P Sagar vs State of Andhra Pradesh case. If the famouns Champakam case necessitated the first amendment to the constitution, the P Sagar case compelled state governments across the country to commission studies to ascertain the list of backward communities that are eligible for affirmative actions, including reservations. Thus, the context was set for the appointment of the Anantharaman commission; the commission placed the backward communities in the then state of Andhra Pradesh into four groups, and proportionately distributed the benefits of the 27% reservations that had been earmarked for backward communities.

It is also pertinent to mention here that the Supreme Court also differentiated in the meaning of the term backwardness in articles 15(4) and 16(4) of the Constitution. For the purpose of Article 15(4), backwardness is to be considered in terms of economic development; whereas, for the purpose of Article 16(4), the meaning of backwardness is strictly social backwardness. When it comes to the Kapu community’s social status in relation to other classes or communities, it is higher—or on par with—any other forward community. Their occupation, agriculture, cannot be considered inferior in any sense. That is what the Muralidhara Rao commission felt way back, in 1980s, when a proposal came before it to consider the Kapu community as socially backward. This was also agreed on by the governments that came into power after this. In modern history, agrarian castes such as the Jats, Kapus, Marathas, and Patidars cannot be considered socially backward, eking out their livelihood through menial or inferior caste linked occupations (as is true for most other backward classes which have been constitutionally recognised as backward communities or scheduled castes).

To emphasise the point—that the Kapu community is neither socially nor economically backward in the constitutional sense—it is important to look at the GO (MS) No 16 of 2016. In this GO, which is nearly 40 pages long, the government listed about 221 occupations/ services/ trades etc for which the government decided to extend 50% subsidy and 50% loan. Trading in agricultural tools and instruments (6 entries) , setting up of agro based industries (34 entries), engineering works (56 entries) animal husbandry ( 6 entries), crafts and art facts manufacturing ( 10 entries) mines and mineral based establishments (28 entries) are some examples from the long list of occupations/ services/ trades etc which will receive economic assistance from the government. Of these, none of the occupations/ services/ trades etc that have been listed can be considered inferior in social status. Besides, it is very clear that no other community which is backward (as defined by the constitution), can take up any of these vocations as their source of living.

Moreover, the economic assistance that the state plans to extend to the students of this community is even more shocking. The Government Order requires the government to extend economic assistance to Kapu students who opt for higher studies in foreign countries, covering costs such as coaching for exams like TOFEL/ GATE/ GRE/ GMAT etc. This clearly establishes the fact that there are no equal opportunities for the youth. Moreover, the unannounced blanket ban on government recruitments across all the departments has led to confusion and distress for those who had qualified. The government, which abides by the market philosophy, can’t take up the responsibility of the creeping market discrimination, nor can it abdicate the neoliberal policy that restrained government from any positive intervention aimed at larger public good. The government is wedded to neoliberal policies; their subsequent structural inability to intervene in the public policy for positive impact lays the foundation for movements demanding reservations by those who are facing market discriminations. Thus, market discrimination cannot, and shall not, be equated with social discrimination. Therefore, the application of policy instruments that are devised and designed for the amelioration of social backwardness would be nothing but a travesty of justice. It is also important to create an Equal Opportunity Commission, along the lines outlined in draft proposed by the constitutional expert N R Madhav Menon, in order to design the new deprivation index. This, in turn, could become a good policy tool to govern the affirmative actions necessitated by the market discrimination.